Dr Sue Mann Explains why Pregnancy Planning is Important and How Preconception Care can Improve Maternal and Child Health Outcomes

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article  |

At any one time, 78% of women of reproductive age (16–44 years)—over 9 million women—in Britain are either actively trying to prevent a pregnancy, are trying to conceive, or are actually pregnant.1,2 Women represent 51% of the population3 and the interplay between trying to prevent a pregnancy (the majority of time), interspersed with periods of trying to conceive or actually being pregnant, continues for the majority of women throughout their fertile lives.

Why is Pregnancy Planning and Prevention Important?

Supporting women to have control over their reproductive lives is important so that:

- most pregnancies are planned or wanted

- women who do not want to be pregnant can effectively prevent themselves becoming pregnant

- health during pregnancy and prior to the first and between pregnancies is optimised.

Currently, 45% of pregnancies and 34% of births are unplanned or ambivalent.1 Unplanned maternities may simply be mistimed but are associated with a higher risk of poor outcomes for mother, infant, and extending into childhood.1 Newer approaches to pregnancy planning and prevention that seek to integrate the traditionally separate contraception and preconception care are needed.

Benefits of Preconception Health

The preconception period refers to the weeks or months before becoming pregnant. In practice, almost 40% of women become pregnant within 1 month of regular sexual intercourse without contraception, and 70% within 3 months.4

Certain groups of women have personal risk factors that are associated with poorer outcomes, such as women who have babies at the extremes of reproductive life,5–7 women who are overweight or obese,8 or women who smoke.9 In 2016, babies born to mothers aged under 20 and over 40 years, or to smokers, had a higher rate of stillbirth and perinatal mortality. Obesity was associated with poor birth outcomes and with offspring being overweight or obese, which often continues into adulthood.10,11 Mental health problems are common in pregnancy and during the postnatal period.2,12 Suicide is one of the most common causes of maternal mortality.12 With a relative increase in pregnancies in older women, there has been an increase in the proportion of mothers with long-term conditions. Two-thirds of maternal mortalities during 2013–2015 were in women who had pre-existing physical or mental health problems.13

Most women who attend for advice about contraception or preconception attend primary care as their preference.14 Around 12% of women at risk of pregnancy do not seek contraception despite not wanting to conceive.1 Equally, only a minority of women attend for preconception advice before trying for a baby.15 In 2011/12, only 31% of women took folic acid before pregnancy (intake of which reduces risk of neural tube defects).16

Because women may not necessarily seek care or initiate change in preparation for pregnancy, adopting a population perspective covers the whole period of time when women are of child-bearing age. This approach recognises that it takes time to embed healthy behaviours and address changes that will have a real impact on risk, such as tackling obesity.2 It also enables the approach to be taken with all women, including the more vulnerable, and not just those who are likely to proactively prepare for pregnancy.17

System-wide approaches at the practice population and wider CCG level are needed to ensure that women already reaching care can make the best possible choices about how, when, and if to have a baby, and new methods are needed to reach those who are not.

Goals of Preconception Care

Preconception care aims to improve maternal and child health outcomes in both the short and longer term so that the next generation can have the best start in life. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates a life-course approach18 that extends from the early years through to the end of the reproductive years. Preconception care needs to be available to all, but in recognising that outcomes are poorer in more disadvantaged communities, the approach of proportionate universalism19 should be addressed where care is proportionate to need rather than demand.

In principle, preconception care helps improve the health of communities through:17

- integrating contraception and preconception care

- continuing preconception care throughout and between pregnancies

- ensuring that higher-risk groups, including those with long-term conditions and additional vulnerabilities, receive more support

- promoting preconception wellbeing messaging across the whole population that align with more general messages

- tackling the wider issues that influence preconception health, such as housing, education, and employment.

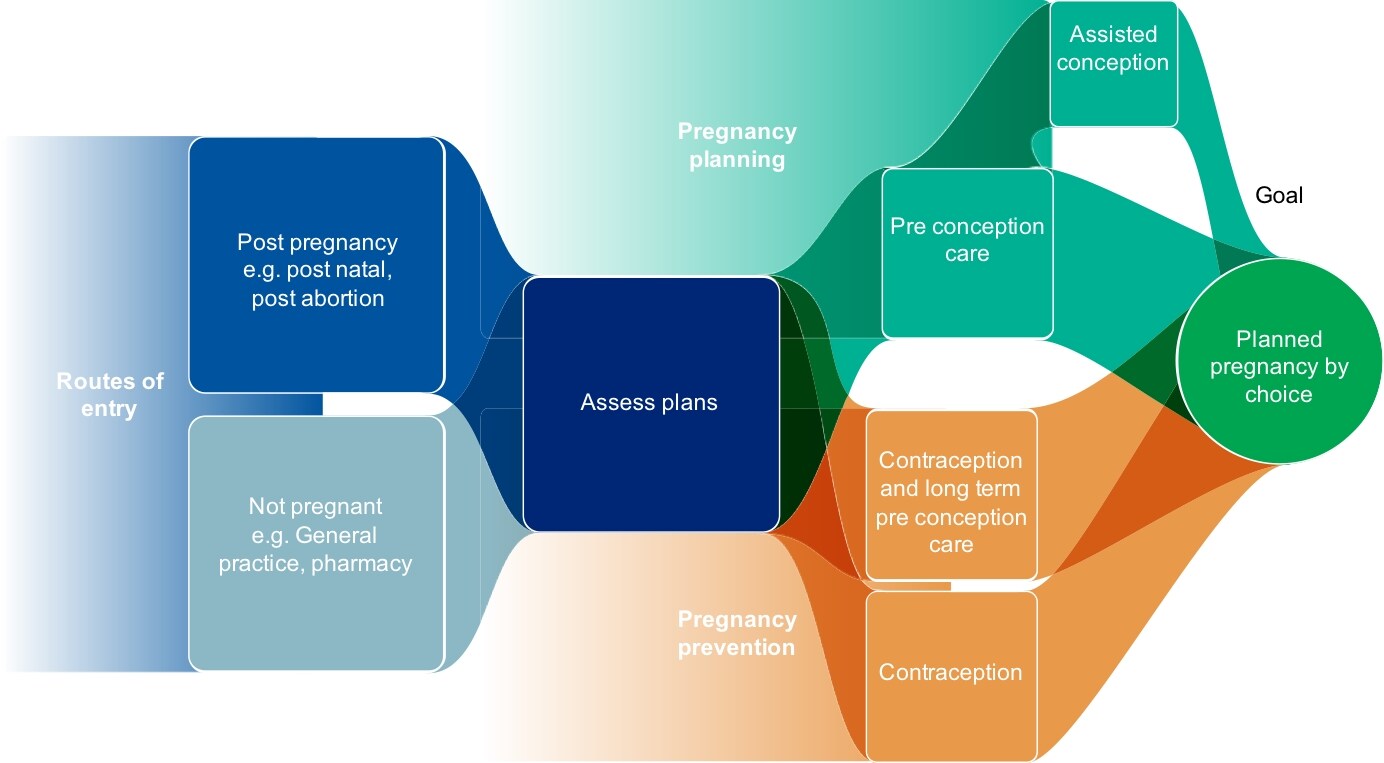

Conceptual Framework for Preventing and Planning Pregnancy

The conceptual framework for preventing and planning pregnancy (see Figure 1) seeks to integrate the planning and prevention offer in healthcare settings.20,21 Opportunities present both in the post-pregnancy setting (abortion and maternity) and the non-pregnancy setting, where general practice plays a key role. This approach is more likely to provide comprehensive advice and reach the women who do not proactively seek care, as well as those who do.

Source: Public Health England. What does the data tell us? Women’s reproductive health is a public health issue. PowerPoint presentation. PHE, 2018. Available at: app.box.com/s/2nrbo3bxddkf685ifu4y6vjpyy2blumj, adapted from Hall J, Mann S, Lewis G et al. Conceptual framework for integrating ‘Pregnancy Planning and Prevention’ (P3). J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2016; 42 (1): 75–76. © 2018 BMJ & Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Reproduced with permission

When can Preconception Care be Offered?

Public Health England advocates three pathways to preconception health:17

1) prior to first pregnancy

2) management of emerging risks

3) next baby and beyond.

Prior to First Pregnancy

There are a range of opportunities to provide preconception care prior to the first pregnancy:

- contraception initiation, maintenance, or discontinuation

- new patient registrations

- cytology

- pregnancy testing

- emergency contraception consultations

- chlamydia screening

- postnatal, post-abortion, post-miscarriage, post-fertility treatment

- baby and vaccination clinics

- other routine primary care appointments.

Details of what should be included in a basic preconception check are described below.

- Discuss plans for a pregnancy if desired, including ensuring that women have an understanding of the reproductive life-course and the impact of their age on pregnancy outcomes.22

- Provide advice about fertility including the normal period of time for conception. For couples in which the woman is aged under 40 years, more than 80% will conceive within 1 year of trying and around 90% at the end of a further year.22

- Check immunity status to rubella and varicella. Women who are non-immune should be offered vaccination.22

- Check cervical screening is up to date. Women who have not been screened before pregnancy are advised to defer having a test while pregnant.22

- Conduct appropriate screening tests, including chlamydia for women under 25 years; offer a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test and full screen for sexually transmitted infections and enquire about experience of domestic violence.22

- Advise about vitamin D and folic acid supplements. 400 mcg of daily folic acid is recommended for women who are trying to conceive, continuing until 12 weeks of pregnancy. Women at higher risk of a neural tube defect (for example if they have a family history, are on anticonvulsant medication, or have diabetes mellitus) are advised to take 5 mg of folic acid daily until 12 weeks of pregnancy; women with sickle cell disease, thalassaemia, or thalassaemia trait should take folic acid 5 mg daily throughout pregnancy.22

- Discuss the need for eating a healthy balanced diet and undertaking regular moderate intensity physical activity.22

- Support weight management. Women who have a body mass index (BMI) below 25 kg/m2 are at lower risk of pregnancy and perinatal complications.23,24 Women with a BMI over 30 kg/m2 can also find it more difficult to conceive25 and have a higher rate of miscarriage as well as pregnancy and delivery complications.8,26 Women who are overweight should be supported to lose weight before becoming pregnant if possible. Even losing 5–10% of bodyweight can have significant benefits26 but weight management support is needed, with sufficient time for women to plan pregnancy over a longer time period. Women who have a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or over are also encouraged to take the higher dose of 5 mg of folic acid.26 Women who are underweight with a BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 are also at risk of poorer outcomes including reduced fertility, preterm birth, and having low birth-weight infants.24

- Give advice on alcohol consumption and substance misuse. The Chief Medical Officers advise women who are trying to conceive or who have become pregnant to avoid alcohol altogether.27 If primary care-based brief interventions to support reduction of alcohol and substance use intake have not been successful, encouraging women to continue contraception while referring onwards for more support from alcohol or substance misuse services where needed is preferable.22

- Provide advice on giving up smoking. Women who are planning to become pregnant should have the opportunity to attend a smoking cessation service.22

- Advise on medication use. Overall, women who are trying to conceive are advised against over-the-counter and herbal remedies. The contraceptive or long-term condition review visit is a good opportunity for women to discuss any implications of regular drug treatments for pregnancy and modification of regimens as needed. An annual review of pregnancy intentions for women of reproductive age is suggested.22

- Advise on use of contraception for family spacing post-natally. Evidence suggests that an inter-pregnancy interval of at least 18 months can optimise perinatal outcomes.2 However, this needs to be weighed against best timing against reproductive age.

Targeted Approaches

Two-thirds of women who died in the UK during or up to 1 year after pregnancy between 2013 and 2015 had pre-existing physical or mental health problems.13 Some women are at higher risk of poor outcomes, and where these risks are potentially modifiable, can be proactively identified. Targeted approaches for preconception care should span the services that these women are likely to be in contact with as well as primary care, who frequently provide generic services to many women at greatest risk, for example those who have:

- genetic conditions

- social problems, with social services or other community services input

- a long-term condition

- a mental health problem

or who:

- use drugs or alcohol

- are obese or overweight

- are migrants.

Next Baby and Beyond

Once a woman has delivered, she transitions from midwifery services into early years and health visiting services. The antenatal appointment with both midwife and health visitor is a good opportunity to initiate discussion of general health issues that are likely to be important in the postnatal period in the context of a new baby or expanding family, in particular plans for postnatal contraception and optimum pregnancy spacing.17 Currently, postnatal contraception is seen as a primary care responsibility although often women do not prioritise their own needs after delivery and frequently attend after they have returned to fertility. Providing immediate post-partum contraception is an ideal way to reach all women, but more than this it can reach women at a time when they are in contact with services but may not be proactively seeking care, so impacting on outcome inequality.

Summary

Support and advice for healthy, planned conception and pregnancy needs to be made available to women throughout their reproductive lives before, between, and after pregnancies. Raising awareness of preconception care, both in women and healthcare staff, could improve outcomes for parents, children, and future generations, especially the most vulnerable. Primary care can offer opportunistic information, advice, and brief interventions as part of a system-wide approach.

Dr Sue Mann

Medical Expert in Reproductive Health

Public Health England

| Key Points |

|---|

A GP pregnancy prevention and planning assessment for a woman of reproductive age should include the following:17,22

BMI=body mass index; STI=sexually transmitted infection; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus © NICE 2018 Pre-conception–advice and management. Clinical Knowledge Summary. Available from: cks.nice.org.uk/pre-conception-advice-and-management#!topicsummary All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system |