Professor A Niroshan Siriwardena Assesses Key Advice from the NICE Guideline on Obstructive Sleep Apnoea/Hypopnoea Syndrome and Related Sleep Disorders

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

The recent publication of NICE Guideline (NG) 202, Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and obesity hypoventilation syndrome in over 16s,1 has important implications for GPs and primary care—the conditions involved are common, they are often overlooked or their diagnosis is delayed, and they can have important physical and psychological health consequences that are amenable to treatment.

The guideline recommendations are in line with the latest evidence on the assessment and treatment of these conditions. This article discusses the symptoms, impact, and prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (OSAHS) and obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), and the recommendations offered by NG202 for diagnosis, management, and referral.

How Common are the Conditions Covered by NG202?

OSAHS—previously termed obstructive sleep apnoea—is a common, but often undiagnosed, group of conditions in which the upper airway repeatedly narrows or closes during sleep.1,2 The resulting temporary cessation of breathing can cause hypoxaemia and hypercapnia,1,2 sleep fragmentation,1,2 and autonomic dysfunction,1 with sympathetic stimulation affecting the cardiovascular system.3,

The condition can occur in association with obesity as OHS—in which the depth or rate of breathing during sleep is reduced—and with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as COPD–OSAHS overlap syndrome, in which oxygen deficiency may be greater than that found with either condition alone.1 Both variants are associated with cardiovascular complications and other comorbidities.1

OSAHS is as common as diabetes, affecting one in 20 adults in the UK, whereas COPD–OSAHS affects one in 100, and OHS between three and four in 1000.1

What Symptoms and Conditions are Associated with OSAHS?

The physical and psychological effects of OSAHS are primarily related to sleep disturbance, and include severe daytime sleepiness1,2 and cognitive impairment.5 These sequelae, in turn, affect people’s ability to participate in social activities, and to work and drive, and negatively impact their quality of life.1,2,6

NICE states that OSAHS should be suspected if people have two or more of the following symptoms:1

- snoring

- witnessed apnoeas

- unrefreshing sleep

- waking headaches

- unexplained excessive sleepiness, tiredness, or fatigue

- nocturia (waking from sleep to urinate)

- choking during sleep

- sleep fragmentation or insomnia

- cognitive dysfunction or memory impairment.

There is a higher prevalence of OSAHS in people who have any of the following conditions:1

- obesity or overweight

- obesity or overweight in pregnancy

- treatment-resistant hypertension

- type 2 diabetes

- cardiac arrythmia, particularly atrial fibrillation

- stroke or transient ischaemic attack

- chronic heart failure

- moderate or severe asthma

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- Down’s syndrome

- nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (sudden loss of vision in one eye due to decreased blood flow to the optic nerve)

- hypothyroidism

- acromegaly.

If left untreated, OSAHS may be associated with serious health problems such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and stroke.1,2,7 Furthermore, both the risk factors and comorbidities of OSAHS are linked to worse outcomes of COVID-19.8

How Should a Person With Suspected OSAHS be Assessed?

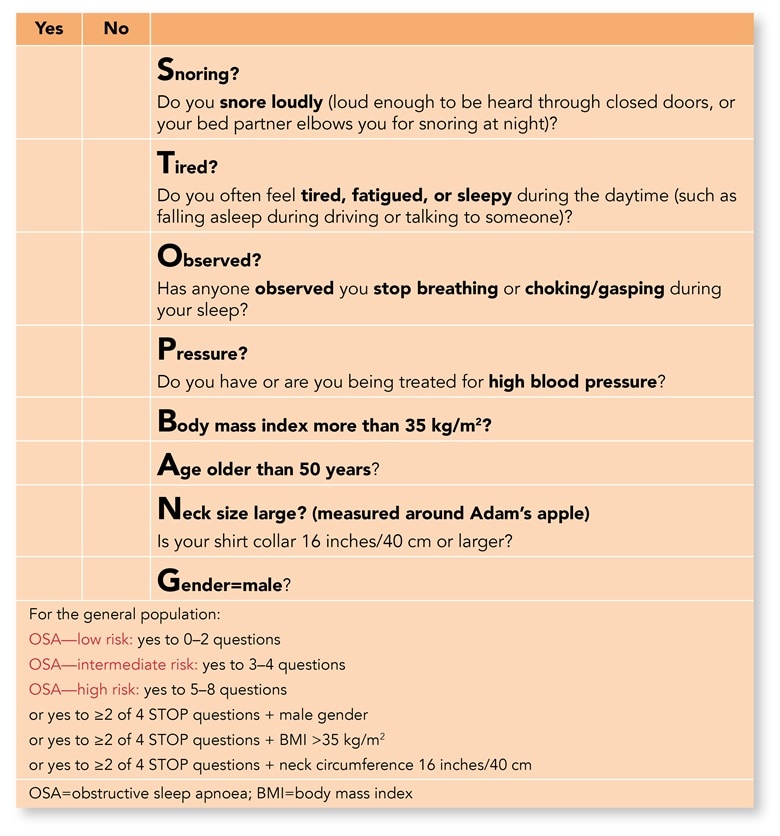

NICE recommends assessing people for OSAHS if they have two or more symptoms associated with the condition.1 Assessment of a person with suspected OSAHS or a related sleep disorder should ideally include a consultation with the patient and their partner and the taking of a sleep history. NICE states that the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) should be used in the preliminary assessment of sleepiness, and that use of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire (see Figure 1) should be considered.1,9,10

STOP-Bang website. STOP-Bang Questionnaire. www.stopbang.ca/osa/screening.php

Reproduced with permission from Dr Frances Chung and the University Health Network (UHN), Canada.

This figure is not for clinical use. If you would like to license use of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire for screening in your own clinical practice, please contact UHN.

The ESS has been shown to exhibit low sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing OSAHS—that is, it is not good at picking up or excluding cases because not all people with OSAHS experience excessive sleepiness—but NICE has deemed it useful for assessment and monitoring.1 The STOP-Bang Questionnaire has greater sensitivity, but poor specificity for diagnosing OSAHS, and there are concerns about its accuracy in certain groups; however, NICE states that it could have a role alongside the ESS in the initial assessment of a person’s symptoms and concerns.1

What do you Need to Know for Making a Referral?

Anyone with two or more of the symptoms associated with OSAHS, particularly if they score highly on the ESS or STOP-Bang Questionnaire, should be referred to a specialist sleep service.1

However, NICE does not recommend using the ESS alone to determine if referral is needed, as not all people will experience excessive sleepiness.1 When making a referral, it is important to include essential information in the referral letter; for example, assessment scores, the effect of symptoms and sleepiness, comorbidities, occupational risk, and oxygen saturation and blood gas values (if available).1

Within the sleep service, certain groups of people should be prioritised for rapid assessment for suspected OSAHS, including those who:1

- have a vocational driving job

- have a job for which vigilance is critical for safety

- have unstable cardiovascular disease, for example, poorly controlled arrhythmia, nocturnal angina, or treatment-resistant hypertension

- are pregnant

- are undergoing preoperative assessment for major surgery

- have non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy.

How is a Diagnosis of OSAHS Made?

The gold standard for diagnosis of OSAHS is overnight polysomnography (PSG) in a specialist sleep laboratory—which involves monitoring of sleep by video and electroencephalography—and measurement of oxygen saturation.1 However, the new guideline advocates the simpler option of home respiratory polygraphy as the primary investigation.1

Respiratory polygraphy involves a band around the chest and abdomen to measure movement, a flow sensor in the nostrils, and an oxygen saturation monitor on a finger. For initial assessment, respiratory polygraphy was found to be more cost effective than the alternative of oximetry for diagnosis.1

If home polygraphy is unavailable, home oximetry can be used. If there are significant symptoms despite negative oximetry results, hospital respiratory polygraphy or PSG can be considered. Hospital polygraphy should also be considered if home polygraphy or oximetry are impractical, or if additional monitoring is needed.1 It should also be noted that oximetry may be inaccurate for differentiating between causes of hypoxaemia in people with heart failure or chronic lung disease.1 If symptoms persist despite normal polygraphy results, PSG should also be considered.1

Classification of OSAHS severity is based on the apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI)—the number of apnoeas and hypopnoeas recorded per hour during a multi-channel sleep study. Mild, moderate, and severe OSAHS are defined as having an AHI of 5–14, 15–29, and 30 or more, respectively.1

What are the Recommended Treatments?

For mild OSAHS without symptoms, or mild symptoms not affecting daily activities, lifestyle advice is the initial recommended step, as treatment is not usually needed (see ‘Lifestyle advice and information’).1

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

When symptoms of mild OSAHS are affecting daily activities or quality of life, fixed-level continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), with telemonitoring for at least 1 year, is recommended in addition to lifestyle advice—or instead of lifestyle advice alone if CPAP is unsuccessful or inappropriate.1 Automatic CPAP, or auto-CPAP, is an alternative to fixed-level CPAP to consider in people with mild OSAHS. Auto-CPAP is generally as effective as fixed-level CPAP and more expensive, but some people find it more comfortable and effective.1 Auto-CPAP adjusts pressure according to changes in position, weight, alcohol, or sleep, and delivers a lower mean pressure overall. As auto-CPAP is as effective as fixed-level CPAP, it is recommended in people with mild OSAHS if:1

- high pressure is needed only for certain times during sleep, or

- they are unable to tolerate fixed-level CPAP, or

- telemonitoring cannot be used for technological reasons, or

- auto-CPAP is available at the same or lower cost than fixed-level CPAP, and this price is guaranteed for an extended period of time.

In moderate or severe OSAHS, CPAP in addition to lifestyle advice should still be offered.1

Please note that In June 2021, the MHRA issued a National Patient Safety Alert for Philips ventilator, CPAP and BiPAP [bi-level positive airway pressure] devices: Potential for patient harm due to inhalation of particles and volatile organic compounds. This applies to all devices manufactured before 26 April 2021. Additionally, it is important to be aware of the COVID-19 infection control implications of CPAP—as it is an aerosol-generating procedure—and whether appropriate measures need to be taken. For more information, see the UK government COVID‑19 guidance on infection prevention and control.

Mandibular Advancement Splints

Consider offering adults with mild, moderate, or severe OSAHS who refuse CPAP a mandibular advancement splint,1 sometimes called a sleep apnoea mouthguard. This is a custom-made dental appliance that fits over the upper and lower dentures and brings the lower jaw forward during sleep, opening the airway to allow air to flow more freely.1 They are only recommended for people aged 18 years or above with good dental and oral health, and are not advised for people who have tooth decay, few or no teeth, or generalised tonic-clonic seizures.1

Positional Modifiers

Positional modifiers are devices used for people with mild or moderate OSAHS whose symptoms are worse when they lie on their back rather than on their side (also called ‘positional OSAHS’); this is to encourage them not to sleep on their backs when other treatments are not tolerated or unsuitable.1 Positional modifiers include the tennis ball technique (a bulky mass such as a tennis ball, bulge of hard foam, or inflated airbags attached between the shoulder blades), lumbar or abdominal binders, semi-rigid backpacks, full-length pillows, and electronic sleep position trainers.1

Management of Rhinitis

Nasal congestion can make OSAHS worse or can be worsened by CPAP, so these patients should be assessed for allergic or vasomotor rhinitis. If present, rhinitis should be treated with topical nasal corticosteroids, and antihistamines if required for allergic rhinitis.1 Patients can be referred to an ear, nose, and throat specialist if needed (for example, in cases where initial treatment is ineffective or anatomical obstruction is suspected).1

Surgical Options

Tonsillectomy should be considered for people with OSAHS who have a body mass index (BMI) of less than 35 kg/m2 but have large obstructive tonsils.1 Occasionally, oropharyngeal surgery is undertaken in people with severe OSAHS who are unable to tolerate CPAP or a mandibular advancement splint despite medically supervised attempts.1

Lifestyle Advice and Information

Once OSAHS is suspected, it is important to provide information on the condition, its impact and risks, and the next steps (see Box 1).1

| Box 1: Information for People with OSAHS, OHS, or COPD–OSAHS Overlap Syndrome1 |

|---|

For people with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (OSAHS), obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (COPD–OSAHS) overlap syndrome who are being referred to a sleep service, provide information on:

For people who have been diagnosed with OSAHS, OHS or COPD–OSAHS overlap syndrome, repeat the information provided at referral [above] and give additional information on:

© NICE 2021. Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and obesity hypoventilation syndrome in over 16s. www.nice.org.uk/ng202 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Lifestyle advice for OSAHS fits with current behavioural advice and interventions, and includes advice on smoking, alcohol, weight, and sleep.1

Smoking causes upper airway inflammation. Alcohol before sleep can increase the risk of apnoea by relaxing the upper airway while reducing sleep quality. Obesity is associated with OSAHS, and also worsens upper airway obstruction. Sleep hygiene advice (for example, adequate sleep time, avoiding caffeine and stimulants before bedtime, regularly exercising, having a quiet, comfortable, darkened bedroom, and winding down before sleep)1 may have a positive effect on sleep quality, and may also help people who are experiencing insomnia. Interventions could include referral to smoking or weight management clinics, and brief alcohol interventions.1

Follow Up and Communication

As with any long-term condition and treatment, it is important that the GP ensures good communication, so that the patient understands their condition and the need for compliance with treatment, and that monitoring for cardiovascular or other complications and specialist follow up are provided, as needed.

Summary

It is important that GPs are aware of and understand the NICE guideline on OSAHS, to support early diagnosis, assessment, and referral when the condition is suspected.

| Key Points |

|---|

OSAHS=obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome; NG=NICE Guideline; OHS=obesity hypoventilation syndrome; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESS=Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

Professor A Niroshan Siriwardena

Professor of Primary and Prehospital Health Care, Community and Health Research Unit, Lincoln Medical School, University of Lincoln

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you to consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; ESS=Epworth Sleepiness Scale; OSAHS=obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome |