Dr Kevin Gruffydd-Jones Explains why NICE Developed a Guideline for Chronic Asthma and Summarises Recommendations About Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article  |

Asthma management in the UK has traditionally been guided by the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) British guideline on the management of asthma.1 However, amid concerns about over-diagnosis in around one-third of patients diagnosed with asthma,2 NICE was commissioned to produce a guideline on the diagnosis and monitoring of asthma, with a special emphasis on the value of objective diagnostic testing. Similarly, headlines such as ‘Asthma inhalers given out almost as a “fashion accessory”, experts warn’3 reflected concerns about inappropriate prescribing of asthma inhalers and contributed to NICE developing a separate guideline on chronic asthma management. Unlike the BTS/SIGN guidelines, the NICE guideline includes an economic evaluation of various diagnostic and management interventions as a key element.

The draft diagnostic NICE guideline was initially produced in 2015 but its recommendations evoked a great deal of controversy so NICE carried out a pilot study into the feasibility of the recommended diagnostic pathway, delaying publication of the guideline. The final guideline, NICE Guideline (NG) 80, was published in November 2017 as a combination of the two draft guidelines and entitled Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management.4 The guideline does not cover severe, difficult-to-control asthma, or the management of acute asthma attacks.

This article does not compare NG80 with existing asthma guidelines (which is dealt with elsewhere5,6) but aims to outline the key elements of NG80 and how these may be put into practice in primary care.

NB Some of the medicines discussed in this article currently (September 2018) do not have UK marketing authorisation for the indications mentioned. The prescriber should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for all clinical decisions. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s guidance on Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices7 for further information.

Diagnosis

The key factors involved in the diagnosis of asthma are:4

- a structured clinical history and physical examination

- objective tests (in adults and children aged 5 years and over).

Box 1 lists some tips designed to help implement NICE recommendations for diagnosing asthma.

| Box 1: Tips for Implementing NICE Recommendations on Diagnosing Asthma |

|---|

|

Structured Clinical History and Examination

Characteristic symptoms of asthma include wheeze, cough, and breathlessness, with a diurnal or seasonal variation. A past or family history of atopic disease (e.g. asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic eczema) should be sought and the presence of specific triggers (e.g. aeroallergens, exercise, tobacco smoke). The importance of occupational asthma is emphasised and patients should be asked whether their symptoms are worse at work and/or better when on holiday (NICE defines ‘holiday’ here as ‘any longer time away from work than usual breaks at weekends or between shifts’.)4

The presence of wheeze on auscultation may be suggestive of asthma but is not diagnostic. Conversely, the absence of wheeze does not exclude a diagnosis of asthma.4 Examination is of value in helping exclude other conditions that might present with symptoms of asthma (e.g. heart failure, bronchiectasis).

Objective Tests

Objective tests for asthma reflect the underlying pathology of reversible airways obstruction, airways inflammation, and airways hyperreactivity. Table 1 shows the cut-off diagnostic values for the various tests.

Table 1: Positive Test Thresholds for Objective Tests for Asthma in Adults, Young People, and Children Aged 5 Years and Over4

| Test | Population | Positive Result |

|---|---|---|

| FeNO | Adults | 40 ppb or more |

Children and young people | 35 ppb or more | |

| Obstructive spirometry | Adults, young people, and children | FEV1/FVC ratio less than 70% (or below the lower limit of normal if this value is available) |

| Bronchodilator reversibility (BDR) test | Adults | Improvement in FEV1 of 12% or more and increase in volume of 200 ml or more |

Children and young people | Improvement in FEV1 of 12% or more | |

| Peak flow variability | Adults, young people, and children | Variability over 20% |

Direct bronchial challenge test with histamine or methacholine | Adults | PC20 of 8 mg/ml or less |

Children and young people | n/a | |

ppb=parts per billion; FeNO=fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1 =forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; PC20=provocative concentration of histamine or methacholine causing a 20% fall in FEV1 | ||

© NICE 2017 Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/ng80 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | ||

Reversible Airways Obstruction

Spirometry is used to ascertain the presence of airways obstruction, defined by a ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC); FEV1/FVC of <0.7 indicates airways obstruction. Where airways obstruction is demonstrated, bronchodilator reversibility testing should be carried out (FEV1 is measured before and 15 minutes after administration of an inhaled bronchodilator, e.g. 400 mcg salbutamol).8

Peak flow variability measured over 2–4 weeks.

Both the above tests may be normal in patients with asthma who are asymptomatic.

Airways Inflammation

Eosinophilic airways inflammation is measured by the concentration of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in exhaled breath using hand-held machines. There are several confounders such as smoking status4 and co-existent rhinitis (the presence of treated or untreated rhinitis can affect FeNO levels).

The pivotal role of FeNO testing in the guideline led to great concerns about its feasibility in general practice due to worries about cost.4,9

Airways Hyperreactivity

Hyperreactivity testing involves administration of inhaled bronchoconstrictors, such as histamine or methacholine, and measuring the concentration of brochoconstrictor to reduce the FEV1 by 20% (PC20). The lower the PC20 value, the higher the airway hyperreactivity. Methacholine challenge testing is largely carried out in specialist respiratory centres;4 histamine and methacholine do not currently have UK marketing authorisation for this use and the prescriber should follow appropriate professional guidance.4,7

Diagnostic Algorithms

The guideline acknowledges that there is no single gold standard test to diagnose asthma.4 The guideline development group has produced objective test algorithms for adults10 and children and young people aged 5 years and over.11 These are, in the author’s opinion, very complicated. Diagnosis of asthma in adults, children and young people, and children aged under 5 years is described below.10,11

Adults (Aged 17 Years and Over)

Two positive tests (FeNO, spirometry, peak flow variability) are required to make a diagnosis. If there is only one positive test of FeNO or spirometry then referral for histamine or methacholine direct bronchial challenge is recommended.4

Children and Young People (Aged 5–16 Years)

A diagnosis of asthma can be made on the basis of a characteristic history and positive spirometry. If spirometry is negative then a positive FeNO test and peak flow variability is required.4

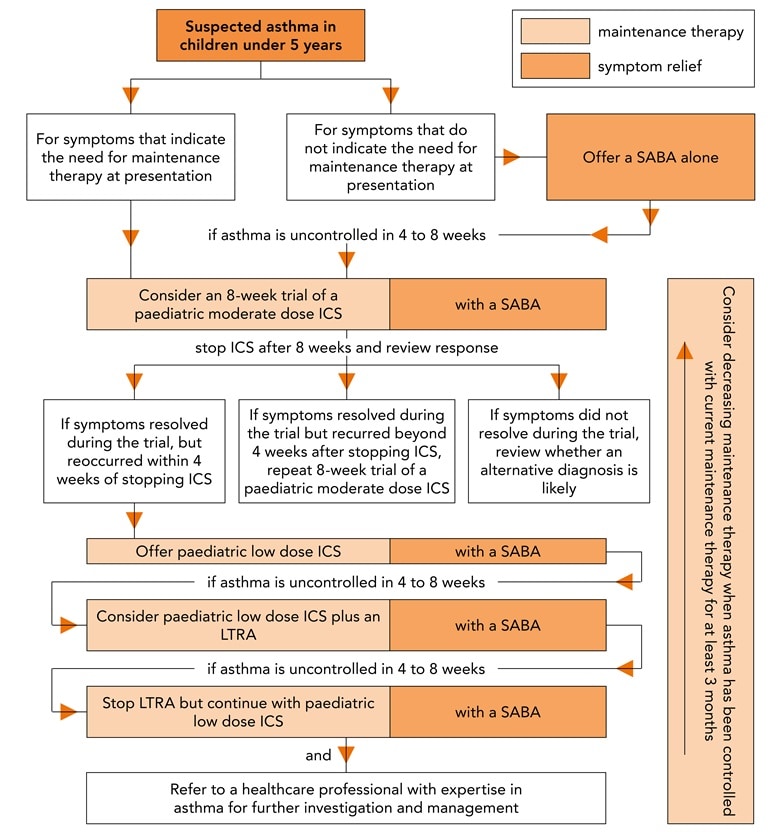

Children Aged Under 5 Years

It is acknowledged that children aged under 5 years will have difficulty in performing objective tests. The diagnostic section advice is vague (‘For children under 5 with suspected asthma, treat symptoms based on observation and clinical judgment, and review the child on a regular basis’).4 The management section recommends considering a trial of ‘a paediatric moderate dose of an inhaled corticosteroid [ICS]’ (defined as more than 200 mcg, up to 400 mcg, budesonide per day or equivalent) for children experiencing symptoms three times weekly or more, or which cause them to wake at night, and assessing the response after 8 weeks.4 If there is a positive response, the ICS should be stopped; if symptoms recur within 4 weeks this is suggestive of a diagnosis of asthma and a paediatric low dose of ICS (less than or equal to 200 mcg budesonide or equivalent) should be given. If symptoms recur beyond 4 weeks, the trial of ICS should be repeated.4

NICE states, however, that the child should have the diagnosis revisited by objective tests when the child is able to perform these.4

Patients Presenting with Acute Asthma

An important point is that if a patient presents with acute asthma then the opportunity should be used to perform objective tests for asthma (for example, FeNO, spirometry, peak flow variability).4 While FeNO and spirometry are mentioned,4 these seem far less practical than measuring the change in peak flow rate with acute therapy (termed ‘peak flow variability’ in the guideline).

Monitoring Asthma Control

NICE Guideline 80 recommends that asthma control is recorded at every review. It specifically recommends that practitioners consider using the validated asthma control questionnaires for adults aged 17 years and over:4

- Asthma Control Test (ACT)12

- a simple test used to assess asthma control, which consists of:

- five questions for adults and young people aged 12 and over

- seven questions for children aged 4–11

- an ACT score of less than 20 indicates poor control.

- a simple test used to assess asthma control, which consists of:

- Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)13

- a five-question version regarding asthma control (ACQ-5) or a full version of seven questions including relief inhaler use and FEV1

- an ACQ score of above 1.0 reflects poor control.

The questionnaires can be obtained via the websites referenced, which also provide further information.

NICE also recommends that FEV1 or peak flow variability is measured at review. The following should also be checked:4

- inhaler technique, by direct observation

- adherence to medication

- possible triggers, including occupation and smoking

- review of the patient’s self-management plan.

If asthma control is noted to be poor, then reconsider the diagnosis (including co-morbidities) and psychosocial factors as well.

In practice, an assessment of exacerbation history should be made as this might additionally influence the decision to escalate therapy.

Pharmacological Management of Chronic Asthma

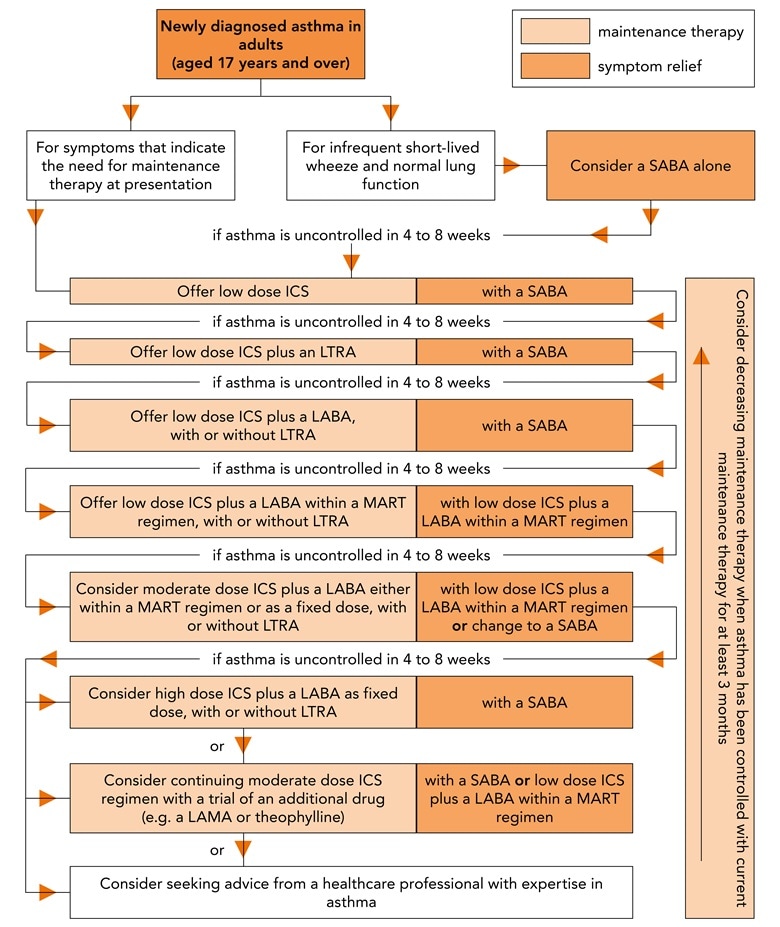

Adults Aged 17 Years and Over

NICE recommends that adults (aged 17 years and over) with infrequent symptoms can be managed with as-needed, short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) relief therapy for infrequent symptoms.4

Low-dose (less than or equal to 400 mcg budesonide or equivalent) inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) should be initiated if symptoms are present three times a week or more, or if the patient wakes at night due to asthma. The response in terms of control should be reassessed after 4–8 weeks.4

If control is not achieved at any stage, the factors mentioned above (under ‘Monitoring asthma control’) should be considered before pharmacological treatment is escalated as summarised below. Treatment de-escalation should be considered at all stages. GPs should refer to the algorithm in Figure 1,14 and NG80 for full details of recommendations for escalating treatment.4

For patients who have poorly controlled asthma with low-dose ICS:

- Add oral leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) to the low-dose ICS:

- this recommendation of adding an LTRA before LABA to low-dose ICS has been particularly controversial. The decision was made on economic grounds relating to the lower cost of LTRAs

- Add long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) in combination with low-dose ICS (LABA/ICS) ± LTRA depending on the initial response to the LTRA. Factors that might lead to initial add-on with LABA are:

- patient concerns about prescription costs (only one prescription with LABA/ICS but two with ICS plus LTRA

- a history of exacerbations (LABA/ICS is more effective than ICS plus LTRA

- good compliance with inhalers and patient preference

- Consider using a single maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) regimen. This involves using a low-dose ICS/LABA (budesonide/formoterol or beclometasone/formoterol) combination inhaler

- Increase to a moderate dose of ICS (more than 400 mcg to 800 mcg budesonide or equivalent) either in a fixed dose or MART regimen, with or without LTRA

- Consider increasing ICS in combination with LABA to high dose (more than 800 mcg budesonide or equivalent), or add low-dose theophylline or tiotropium, or refer to a respiratory specialist.

© NICE 2018 Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. NICE Guideline 80. Tools and resources. Algorithm F: Pharmacological treatment of chronic asthma in adults aged 17 and over. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/ng80 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

SABA=short-acting beta2 agonist; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; LTRA=leukotriene receptor antagonist; LABA=long-acting beta2 agonist; MART=maintenance and reliever therapy; LAMA=long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists

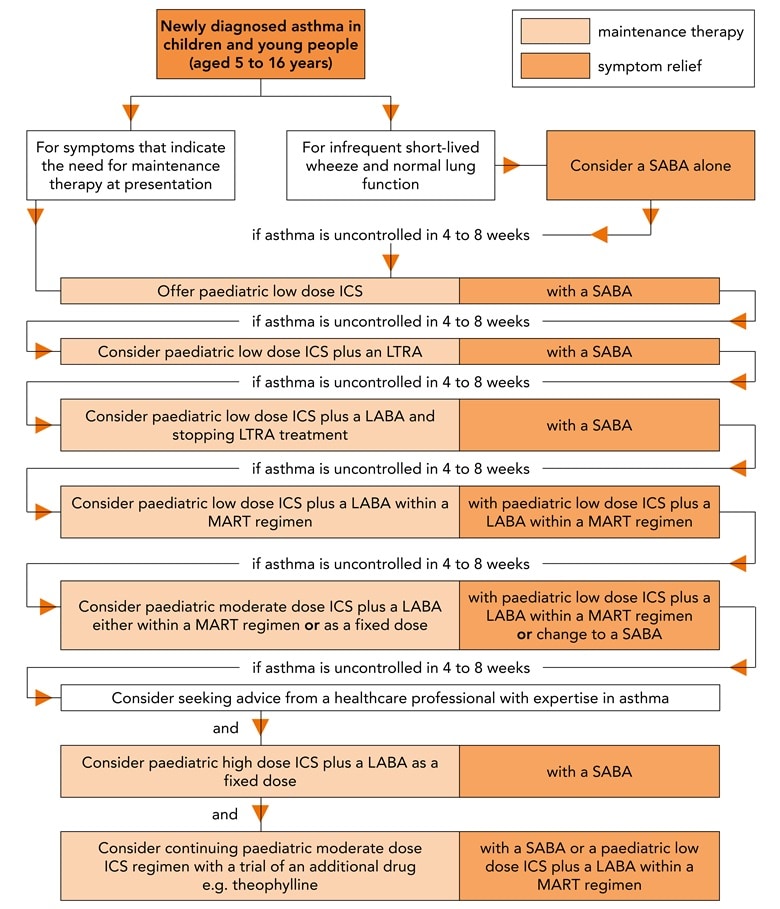

Children and Young People Aged 5–16 Years

NICE recommends intermittent use of SABA for children and young people with intermittent symptoms and normal lung function.4 If there are symptoms three or more times weekly or if the child wakes up at night, a paediatric low dose (200 mcg budesonide equivalent per day) should be initiated. If control remains suboptimal after 4–8 weeks, then consider factors such as adherence, inhaler technique, etc. before escalating treatment sequentially as summarised below. GPs should refer to the algorithm in Figure 2,15 and NG80 for full details of recommendations for escalating treatment.4

- Add LTRA to paediatric low-dose ICS

- Stop LTRA. Prescribe a low-dose ICS/LABA combination.

- Prescribe a low-dose ICS/LABA MART regimen:

- the MART regimen is not licensed for children under 12 years. Prescribe a paediatric moderate dose (budesonide 400 mcg equivalent/LABA combination)

- Refer to a respiratory specialist; that is, do not exceed 400 mcg budesonide equivalent per day.

© NICE 2018 Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. NICE Guideline 80. Tools and resources. Algorithm E: Pharmacological treatment of chronic asthma in children and young people aged 5 to 16. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/ng80 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

SABA=short-acting beta2 agonist; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; LTRA=leukotriene receptor antagonist; LABA=long-acting beta2 agonist; MART=maintenance and reliever therapy

Children Aged Under 5 Years

If a child responds to a trial of therapy (see ‘Children aged under 5 years’ under ’Diagnostic algorithms’, above), then low-dose paediatric maintenance ICS (budesonide 200 mcg per day) therapy should be introduced.

If control is not maintained, then issues such as adherence and inhaler technique should be considered at each stage and treatment escalated as summarised below. GPs should refer to the algorithm in Figure 3,16 and NG80 for full details of recommendations for escalating treatment.4

- Add LTRA to low-dose ICS

- Stop LTRA, but continue with paediatric low-dose ICS and consider referral to a ‘healthcare professional with expertise in asthma’.

© NICE 2018 Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. NICE Guideline 80. Tools and resources. Algorithm D: Pharmacological treatment of chronic asthma in children under 5. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/ng80 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

SABA=short-acting beta2 agonist; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; LTRA=leukotriene receptor antagonist

De-escalating/Acute Escalation of treatment

NICE recommends that maintenance therapy should be decreased if asthma control is maintained for at least 3 months. The guideline also recommends that if maintenance therapy needs to be escalated for 7 days in patients aged 5 years and over as part of self-management, the ICS dose should be quadrupled (rather than doubled as is often recommended). The maximum licensed daily dose should not be exceeded.4

Conclusion

The development of NG80 has been hampered by controversy, especially surrounding the recommendations concerning diagnosis. These recommendations emphasise the importance of objective tests in adults and children aged 5 and over in establishing a diagnosis of asthma, but concerns have been expressed about the availability and cost of FeNO testing in particular.

Recommendations regarding the diagnosis and management of asthma (e.g. the first addition of LTRA to ICS versus addition of LABA) conflict with those of more established national and international asthma guidelines and the confusion this creates is an additional barrier to the implementation of NG80.

In order for these barriers to be overcome, commissioners need to ensure that there is timely access, for all patients, to the recommended tests. Confusion concerning the different guidelines could be further addressed by consensus between NICE and BTS/SIGN.

Dr Kevin Gruffydd-Jones

GP, Box, Wiltshire

| Key Points |

|---|

ICS=inhaled corticosteroid |

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; NG=NICE Guideline; QOF=quality and outcomes framework |