Dr Patrick Holmes Reviews the Recommendations of NICE Guideline 203, Chronic Kidney Disease: Assessment and Management

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs, ICSs, and clinical pharmacists in general practice at the end of this article |

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a long-term, progressive condition with a variety of causes that is characterised by structural and functional changes to the kidney. It is typically defined as a reduction in kidney function—indicated by a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m² and/or markers of kidney damage (albuminuria, haematuria, or abnormalities detected through laboratory testing or imaging)—that is present for at least 3 months.1

CKD is a common problem. In 2014, Public Health England estimated that 2.6 million people aged 16 years and over were living with stage 3–5 CKD in the UK,2 and the prevalence of CKD has continued to grow in the UK and worldwide.3 It is predicted that, by 2040, CKD will be the fifth-leading cause of death globally.4 The increase in the number of individuals with CKD is partly related to the fact that people are living longer, but is largely due to the rise in diabetes and hypertension in high-income countries like the UK, which account for most cases of CKD.5 Most deaths caused by CKD are attributable to cardiovascular disease (for example, heart failure and myocardial infarction).3,6

The health burden of CKD on the NHS is huge: the most recent National chronic kidney disease audit identified the condition as a major risk factor for hospital admission.7,8 The financial burden of CKD is also high: in 2009–2010, the NHS spent an estimated £1.45 billion on CKD, approximately half of which was attributable to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).9

CKD is progressive and, usually, insidious—the majority of affected individuals are asymptomatic until the disease becomes advanced (for example, at an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2).10,11 Lost kidney function cannot be reversed; therefore, early identification and optimal management with treatments that reduce kidney decline are key in primary care.

Why the Need for New NICE Guidance?

The previous NICE Guideline on CKD was published in 2014. Since then, concerns have been raised regarding the previously recommended adjustment to eGFR based on ethnicity, which may have led to an increase in health inequalities.12,13 In addition, two large kidney outcomes trials demonstrating the benefits of sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is) in selected cohorts of people living with CKD have been published since the previous NICE Guideline on CKD was issued.14,15 Also, better tools, such as the 4-variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation, have since been developed and validated that identify those at risk of developing ESRD.16

The 2021 NICE Guideline on CKD provides updated recommendations that take this new information into account.10 This article discusses the revised NICE recommendations on the identification and management of CKD.

Investigations for CKD

The NICE Guideline on CKD identifies two key tests for assessing the possibility of CKD:10

- creatinine-based estimate of GFR —clinical laboratories should estimate GFRcreatinine in adults using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (or CKD-EPI) Equation. eGFR should be reported as a whole number if it is 90 ml/min/1.73 m2 or less. An eGFR result less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 in an adult not previously tested should be confirmed by repeating the test within 2 weeks

- proteinuria —for the initial detection of proteinuria in adults, children, and young people, urine albumin:creatinine ratio (uACR) should be used rather than protein:creatinine ratio because of its greater sensitivity for low levels of proteinuria. There is no requirement for the first sample to be an early-morning sample. An ACR result of between 3 and 70 mg/mmol should be confirmed using a subsequent early morning sample. A repeat sample is not needed if the initial ACR is 70 mg/mmol or more.

NICE also recommends that renal ultrasound is offered to all adults with CKD who:10

- have accelerated progression of CKD

- have visible or persistent invisible haematuria

- have symptoms of urinary tract obstruction

- have a family history of polycystic kidney disease and are older than 20 years

- have an eGFR of less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m3 (GFR category G4 or G5)

- are considered by a nephrologist to need a renal biopsy.

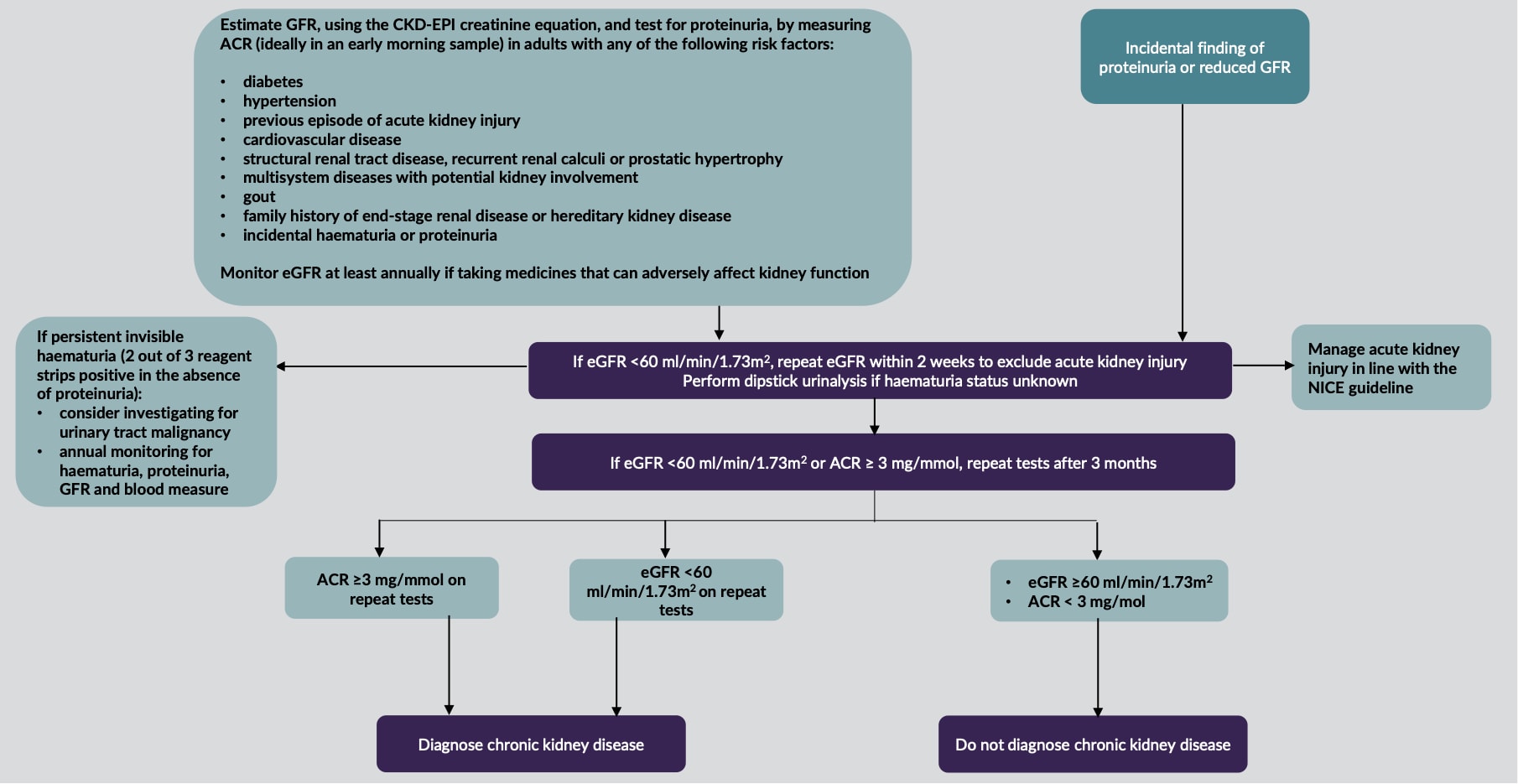

Figure 1 shows NICE’s visual summary of the process of identifying CKD in adults.17

CKD=chronic kidney disease; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; CKD-EPI=Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; ACR=albumin:creatinine ratio; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate

© NICE 2021. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management. NICE Guideline 203. Visual summary: identifying chronic kidney disease in adults. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203/resources/visual-summary-identifying-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults-pdf-9206256493

All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

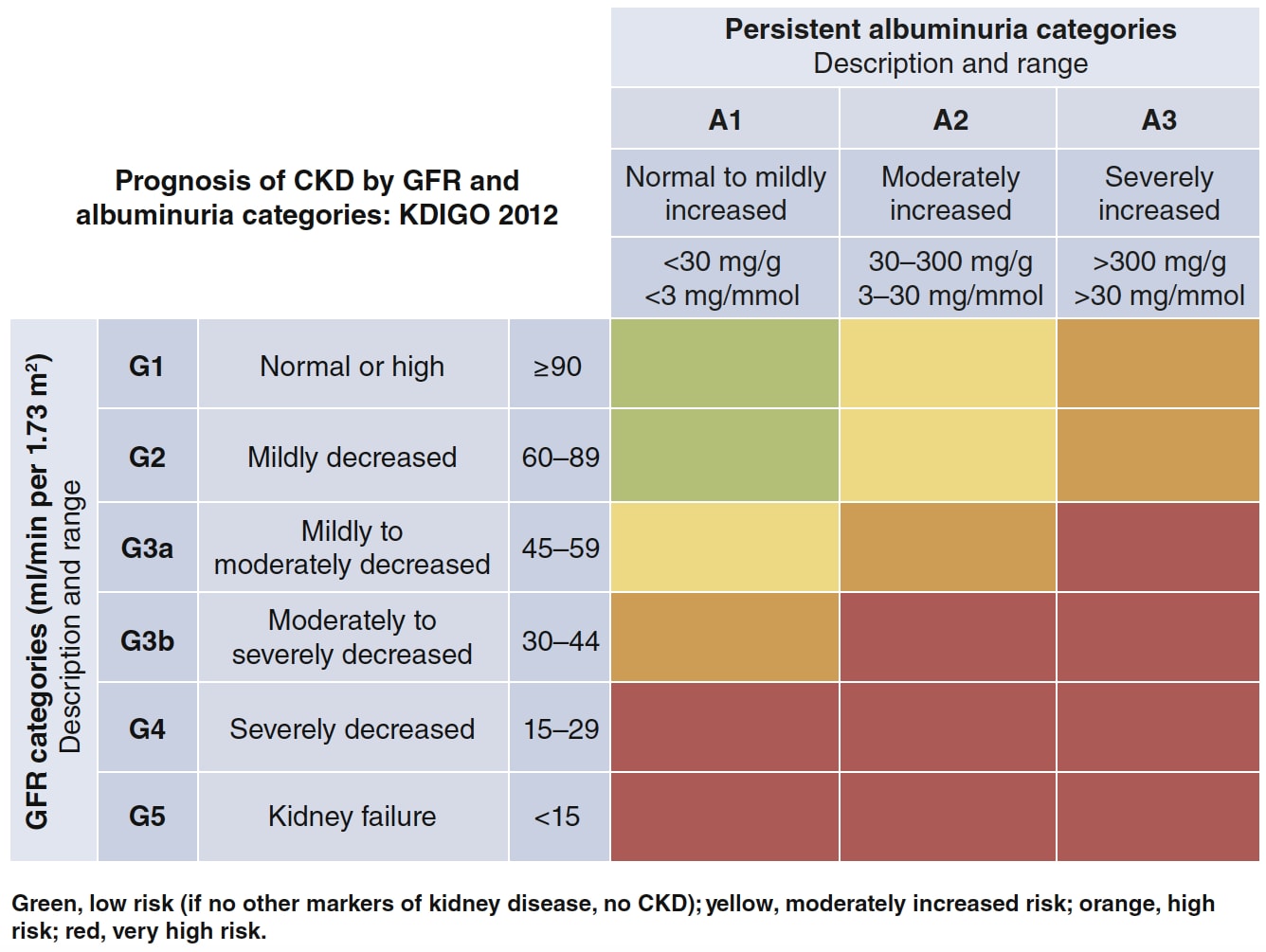

Table 1: KDIGO Nomenclature for Classifying CKD18

KDIGO=Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; CKD=chronic kidney disease; GFR=glomerular filtration rate

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl 2013; 3 (1): 1–150. Available at: kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf

Reproduced with permission.

The advantage of the KDIGO-derived table adopted by NICE is that it is much easier to see which individuals are at risk of CKD progression and harm by integrating both tests for CKD. This, in turn, makes it easier to identify the minimum frequency of eGFR testing (see Table 2).

Table 2: Minimum Number of Monitoring Checks (eGFR:creatinine) Per Year for Adults, Children, and Young People With or At Risk of CKD10,[A]

| ACR Category A1: Normal to Mildly Increased (< 3 mg/mmol) | ACR Category A2: Moderately Increased (3–30 mg/mmol) | ACR Category A3: Severely Increased (> 30 mg/mmol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFR category G1: normal and high (90 ml/min/1.73 m2 or over) | 0 to 1 | 1 | 1 or more |

| GFR category G2: mild reduction related to normal range for a young adult (60 to 89 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 0 to 1 | 1 | 1 or more |

| GFR category G3a: mild to moderate reduction (45 to 59 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| GFR category G3b: moderate to severe reduction (30 to 44 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 1 to 2 | 2` | 2 or more |

| GFR category G4: severe reduction (15 to 29 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| GFR category G5: kidney failure (under 15 ml/min/1.73 m2) | 4 | 4 or more | 4 or more |

Note A: ACR monitoring should be individualised based on a person’s individual characteristics, risk of progression, and whether a change in ACR is likely to lead to a change in management | |||

CKD Progression

NICE defines accelerated progression of CKD in adults as:10

- a sustained decrease in GFR of 25% or more and a change in GFR category within 12 months, or

- a sustained decrease in GFR of 15 ml/min/1.73 m2 per year.

Risk Assessment, Referral Criteria, and Shared Care

One major change that NICE has made is to recommend that healthcare practitioners (HCPs) use the 4-variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation,16 which uses the variables age, sex, eGFR, and uACR, both when communicating risk to adults with CKD and their family members or carers, and when identifying adults with CKD who would benefit from referral for specialist assessment.10 The rationale is simple: the equation is more sensitive and more specific than the previous eGFR threshold that was central to the 2014 NICE guidance.10 This means that people who will progress to needing renal replacement therapy (defined as the need for dialysis or transplant) are identified earlier. Full referral criteria can be found in Box 1.10

| Box 1: Referral Criteria for Specialist Assessment of Adults with CKD10 |

|---|

Refer adults with CKD for specialist assessment (taking into account their wishes and comorbidities) if they have any of the following:

[A] NICE. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE Guideline 136. NICE, 2019. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng13 |

When discussing referral, it is important that this is done in the spirit of the recently published NICE Guideline 197, Shared decision making.19 Use everyday, jargon-free language to communicate information on risk, and explain any technical and medical terms clearly.10 In addition, allow enough time during the consultation to give information on risk assessment and to answer any questions.10

Treatment to Prevent Further Decline in Kidney Function

Lifestyle Advice

It is essential to reinforce the importance of taking exercise and achieving a healthy weight, and to emphasise the significance of smoking cessation to smokers.10 It is also important to give dietary advice regarding potassium, phosphate, calorie, and salt intake appropriate to the severity of CKD.10 Low-protein diets should not be offered to adults with CKD.10 Because chronic use of NSAIDs may be associated with CKD progression, and acute use with a reversible decrease in GFR, caution should be exercised when giving NSAIDs to people with CKD for prolonged periods, and their effects on GFR should be monitored.10

Blood Pressure Control

While bearing in mind the degree of frailty and multimorbidity (see also NICE Guideline 136, Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management20), blood pressure (BP) targets in patients with CKD are driven by the degree of albuminuria, as follows:10

- in adults with CKD and an ACR under 70 mg/mmol, aim for a clinic systolic BP below 140 mmHg (target range 120–139 mmHg) and a clinic diastolic BP below 90 mmHg

- in adults with CKD and an ACR of 70 mg/mmol or more, aim for a clinic systolic BP below 130 mmHg (target range 120–129 mmHg) and a clinic diastolic BP below 80 mmHg

- in children and young people with CKD and an ACR of 70 mg/mmol or more, aim for a clinic systolic blood pressure below the 50th percentile for height.

The choice of BP-lowering medication will depend on the level of albuminuria and on whether the individual has diabetes.10,20

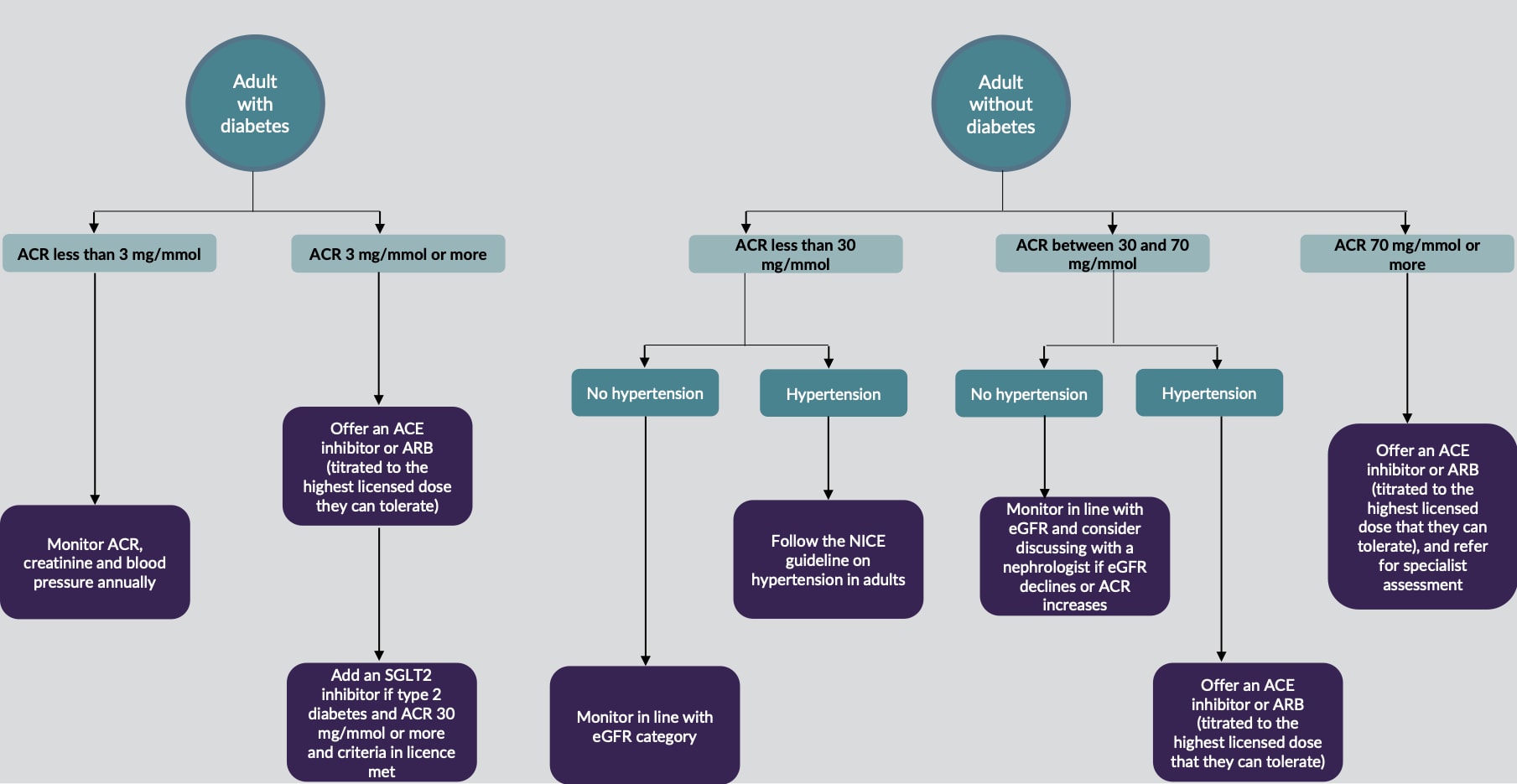

Figure 2 is NICE’s visual summary of the process of managing proteinuria.21

CKD=chronic kidney disease; ACR=albumin:creatinine ratio; ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; SGLT2=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2

© NICE 2021. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management. NICE Guideline 203. Visual summary: chronic kidney disease (G1–5, A1–3)—managing proteinuria. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203/resources/visual-summary-chronic-kidney-disease-g15-a13-managing-proteinuria-pdf-9206256495

All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Antagonists

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) antagonists are frequently indicated in CKD because they are renoprotective.22 When using RAAS antagonists in people with CKD, it is important that the optimal tolerated dose is used, and that eGFR and serum potassium are monitored before starting treatment and within 1–2 weeks of starting or uptitrating the dose.10 If an adult’s eGFR falls by 25% or more, or if serum creatinine rises by 30% or more, it is important to investigate other causes of deterioration in kidney function, such as volume depletion or concurrent medication use. If none are found, the RAAS antagonist should be stopped or reduced to a previously tolerated dose, and an alternative antihypertensive medication added if needed.10 Do not offer a combination of RAAS antagonists to adults with CKD.10 See the guideline for more information.10

Sodium–Glucose Co-transporter-2 Inhibitors

Over the past 2 years, SGLT-2is, originally developed for the treatment of raised blood glucose in type 2 diabetes, have been demonstrated to reduce the rate of eGFR decline and adverse kidney and cardiovascular outcomes.14,15 This has led to a paradigm shift in the role of SGLT-2is—for example, a licence change for dapagliflozin reflects its new indication in the management of CKD.23

The updated NICE guidance on CKD recommends that, in addition to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) at an optimised dose, an SGLT-2i should be offered to patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes if ACR is greater than 30 mg/mmol and if they meet the criteria (including relevant eGFR thresholds) of the marketing authorisation of the specific drug used.10 These patients should also be monitored for volume depletion and eGFR decline.10 However, NICE is reviewing the evidence on the use of SGLT-2is in people with CKD and type 2 diabetes, and may revise the related recommendations in an update due to be published on 24 November 2021.10

Diagnosing and Managing Anaemia in CKD

The kidney plays an important role in the production of red blood cells by secreting the hormone erythropoietin.24 As kidney function deteriorates, so does its ability to produce this hormone, resulting in an increased risk of anaemia.24 If eGFR is greater than 60 mg/mol/1.73 m2, anaemia is unlikely to have been caused by CKD, and other causes should be investigated.10 However, if eGFR is less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, other causes of anaemia should be investigated appropriately, but CKD is likely to be the cause.10

NICE recommends using the percentage of hypochromic red blood cells (target more than 6%) or, if this is not possible, reticulocyte haemoglobin content (target less than 29 pg), to determine response to iron therapy every 3 months (every 1–3 months in individuals receiving haemodialysis).10 If these tests are unavailable or the person has thalassaemia/thalassaemia trait, then a combination of transferrin saturation (target less than 20%) and serum ferritin (target less than 100 mcg/l) should be used to assess the response.10 Erythropoietic-stimulating agent therapy should not be started in the presence of absolute iron deficiency without also managing the iron deficiency.10

What Changes are Likely in the Expected update to NICE Type 2 Diabetes Guidance?

NICE is currently developing its guidance Type 2 diabetes in adults: management—SGLT2 inhibitors for chronic kidney disease (update).25 NICE proposes to extend the recommendation on the use of SGLT-2is as kidney-protection agents in type 2 diabetes. The draft guidance reaffirms the advice of NICE Guideline 203 that patients with CKD A3 (ACR more than 30 mg/mmol) who meet the marketing authorisation criteria should be offered an SGLT-2i, but also asks HCPs to consider an SGLT-2i, in addition to an ARB or ACEi, in people with CKD A2 (ACR 3–30 mg/mmol) who meet the marketing authorisation criteria.25

Summary

The updated NICE guidance on CKD affirms the importance of early detection for this clinically and economically important cluster of conditions. The most eye-catching changes are the addition of an SGLT-2i as a specific therapy for the prevention of CKD progression (the first new therapy since the development of ARBs), and the introduction of the 5-year risk of needing renal replacement therapy to identify people suitable for specialist referral.

| Useful Resources |

|---|

|

| Key Points |

|---|

CKD=chronic kidney disease; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; uACR=urine albumin:creatinine ratio; BP=blood pressure; SGLT-2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; ACEi=angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker |

Dr Patrick Holmes

GP Partner, St George’s Medical Practice, Darlington; local clinical commissioner for diabetes; trustee and committee member for the Primary Care Diabetes Society; Primary Care Diabetes NIHR Research Lead for the North East

| At the time of publication (November 2021), some of the drugs discussed in this article did not have UK marketing authorisation for the indications discussed. Prescribers should refer to the individual summaries of product characteristics for further information and recommendations regarding the use of pharmacological therapies. For off-licence use of medicines, the prescriber should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for the decision. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information. |

| Implementation Actions for Clinical Pharmacists in General Practice |

|---|

Written by Ziad Laklouk, Senior Clinical Pharmacist, Soar Beyond Ltd and Didcot Primary Care Network The following implementation actions are designed to support clinical pharmacists in general practice with implementing the guidance at a practice level.

[A] NICE. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE Guideline 5. NICE, 2015. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng5 [B] NICE. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical Guideline 181. NICE, 2014 (last updated 2016). Available at: www.nice.org.uk/cg181 [C] NICE. Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management. NICE Guideline 196. NICE, 2021. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng196 [D] NICE. Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. NICE Guideline 158. NICE, 2020. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng158 CKD=chronic kidney disease; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; uACR=urine albumin:creatinine ratio; DOAC=direct oral anticoagulant; NSAID=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ACEi=angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; COX-2=cyclo-oxygenase-2; SMR=structured medication review; CVD=cardiovascular disease; CHD=coronary heart disease; PAD=peripheral arterial disease; MHRA=Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; SGLT-2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor |

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; CKD=chronic kidney disease; SGLT-2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor |