Dr Natasha Halliwell Offers 10 Top Tips on the Identification and Management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Young People

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common brain development disorder in children and young people (CYP), with a global prevalence in childhood estimated to be around 5%.1 It is thought to be under-identified, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in the UK.2,3

ADHD is defined by age-inappropriate behaviours that emerge as the child grows: severe and persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity that in turn leads to significant impairment in development and function affecting school life, family relationships, friendships, and self-esteem.4 Typically, symptoms appear at 3–7 years of age,5 and between 60% and 70% of patients with ADHD will have persistent functional impairment into adulthood.6 Untreated ADHD can have far-reaching, long-lasting, negative impacts on an individual’s life. In the UK, screening for ADHD in schools is not currently recommended.4

1. Identify ADHD Before it can Present at Crisis Point

Common symptoms associated with ADHD include mood problems, low self-esteem, problems with planning and organisation, and difficulty with peer interactions.6 In adolescents, school absences, lower educational performance and attainment, disruptive behaviours, and teenage pregnancy may denote ADHD.6,7 Identifying CYP with suspected ADHD can be complex. Preschool children with ADHD often present with hyperactivity, whereas inattention is more prevalent among adolescents.6

In addition to the variety of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity symptoms, CYP should also meet specific criteria (see Box 1).8 Three types of ADHD exist, according to the predominant symptom(s): inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity (see Box 2).9

| Box 1: DSM-5 Criteria for the Diagnosis of ADHD8 |

|---|

A. A persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development, as characterized by (1) and/or (2):

Note: The symptoms are not solely a manifestation of oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or failure to understand tasks or instructions. For older adolescents and adults (age 17 and older), at least five symptoms are required. a. often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities (e.g., overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate) b. often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading) c. often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g., mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction) d. often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked) e. often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized work; has poor time management; fails to meet deadlines) f. often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers) g. often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones) h. is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for older adolescents and adults, may include unrelated thoughts) i. is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments)

Note: The symptoms are not solely a manifestation of oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or a failure to understand tasks or instructions. For older adolescents and adults (age 17 and older), at least five symptoms are required. a. often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat b. often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining in place) c. often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate (Note: In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless) d. often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly e. is often ‘on the go,’ acting as if ‘driven by a motor’ (e.g., is unable to be or uncomfortable being still for extended time, as in restaurants, meetings; may be experienced by others as being restless or difficult to keep up with) f. often talks excessively g. often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed (e.g., completes people’s sentences; cannot wait for turn in conversation) h. often has difficulty waiting his or her turn (e.g., while waiting in line) i. often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations, games, or activities; may start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission; for adolescents and adults, may intrude into or take over what others are doing) B. Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present prior to age 12 years C. Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms are present in two or more settings (e.g., at home, school, or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities) D. There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, academic, or occupational functioning E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, personality disorder, substance intoxication or withdrawal). DSM-5=Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fifth edition; ADHD=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Box 2: ADHD: How Common is it?9 |

|---|

There are three different subtypes of ADHD:

The global prevalence of ADHD in children is estimated to be around 5%, while studies based on US populations (where rates of diagnosis and treatment tend to be highest) estimate the rate at between 8% and 10%. ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in boys than girls. Prevalence ratios are generally estimated at between 2 and 5 to 1, while clinic populations show the ratio as high as 10 to 1. This sex difference may be due to the fact that boys present more often with disruptive behaviour that prompts referral, whereas girls more commonly have the inattentive subtype and have lower comorbidity with ODD and conduct disorder. In the UK, prevalence of ADHD in adults is estimated at 3% to 4%, with a male to female ratio of approximately 3 to 1. ADHD=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder © NICE 2019 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Available from cks.nice.org.uk/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

2. Keep Inattentive ADHD in Mind, Particularly in Girls

The predominantly inattentive presentation of ADHD often presents later than other types.6 Inattention is difficult to control, but may respond to high levels of instant reward or reinforcement, such as online gaming. However, attention at school is usually more challenging, because rewards are often less immediate.

ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in boys than girls, and UK prevalence ratios are around 2–3 to 1,2 whereas in clinic populations the ratio can be as high as 10 to 1.9 However, ADHD may be under-recognised and underdiagnosed in girls.2 This may be because boys present more often with disruptive behaviour that prompts referral, whereas girls more commonly present with inattention, and have lower comorbidity with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder.9 Additionally, girls may be more likely to receive an incorrect diagnosis of another mental health or neurodevelopmental condition.4

3. Be Alert for Groups at High Risk of ADHD

The cause of ADHD is unknown, but involves genetic and environmental factors thought to lead to altered brain neurochemistry and structure. Certain groups of CYP may have increased prevalence of ADHD compared with the general population (see Box 3).4 Heritability for ADHD has been shown to be more than 70%, and family members of CYP with ADHD may have similar symptoms, although not always with a diagnosis of their own.10

| Box 3: Groups with an Increased Prevalence of ADHD4 |

|---|

Be aware that people in the following groups may have increased prevalence of ADHD compared with the general population:

ADHD=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder © NICE 2019 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/ng87 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Key risk factors for ADHD include low birth weight and maternal smoking during pregnancy.10 Other risk factors include lead exposure, iron deficiency, maternal alcohol use during pregnancy, psychosocial adversity, and adverse maternal mental health.10 A 2012 report for the Children’s Commissioner found that there was an increased ADHD prevalence of 11.7% for male young offenders and 18.5% for female young offenders.11

4. Determine the Severity of Impairment

Assessment of CYP who present in primary care with symptoms of ADHD should explore the severity and impact on the person and their family.4 This includes the extent of symptoms, level of functional impairment, adverse effects on family and peer relationships, psychological impact, and pervasiveness across settings—most commonly home and school (see Table 1).

Table 1: Assessing the Extent of Functional Impairment

| Stage of Development | Examples of Functional Impairments |

|---|---|

| Primary school |

|

| Secondary school |

|

| Older adolescence |

|

If symptoms are causing an adverse impact on a patient’s development or family life, consider:4

- a period of watchful waiting of up to 10 weeks

- offering parents or carers a referral to group-based ADHD-focused support (this should not wait for a formal diagnosis of ADHD).

Persistent problems causing moderate impairment should inform a referral to secondary care, and those with severe impairment should also be directly referred for secondary care assessment.4

5. Explore Local Referral and Diagnostic Pathways

Referral to secondary care can be via health, education, social care, or youth justice professionals, and preferably by someone with day-to-day knowledge of the individual affected. Care pathways can vary locally, and should aim to transition seamlessly into adult ADHD services.

Diagnosis of ADHD in pre-school children is not considered to be reliable because current behavioural symptom questionnaires are not sensitive at this stage.12 Standardised questionnaires tend to be valid from 6 years of age, and ADHD medication is not licensed for children under 6 years.

Formal ADHD diagnoses should be made by a healthcare professional with training and expertise in diagnosing ADHD.4 Symptoms should fulfil the criteria specified in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.8 Children must have at least six of nine inattentive or hyperactive–impulsivity criteria or both, whereas in older adolescents at least five criteria must be met (see Box 1).8

6. Gather Information to Support Referral

Symptom questionnaires, completed by parents/carers and teachers, provide valuable adjuncts to ADHD diagnosis and, when submitted with the referral, can help to speed up the process in secondary care. These include the Conners Rating Scale, SNAP-IV Teacher and Parent Rating Scale, and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, depending on local preferences, and may be supplemented with a young person’s self-assessment, school reports, and ADHD-relevant information from other sources, such as educational psychology assessment reports.

7. Consider Differential Diagnoses and Comorbidities

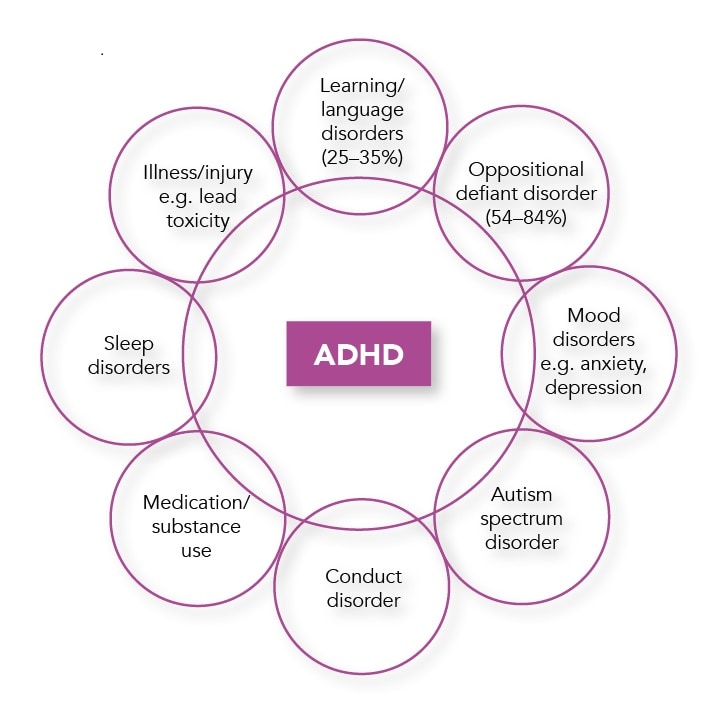

Symptoms of ADHD overlap with other disorders such as autistic spectrum disorder,13 and access to care pathways may differ. About two-thirds of CYP with ADHD have comorbidities, most commonly ODD and conduct disorder (see Figure 1).6 Comorbidities can develop alongside or as a consequence of ADHD, and vigilance for ADHD symptoms as a possible explanation for other problems is recommended. Be aware that conditions such as traumatic brain injury, lead exposure, thyroid disorder, absence seizures, and intoxication or withdrawal from substances can mimic ADHD symptoms.6,10

ADHD=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Consider referring infants and toddlers with inattentiveness for auditory or visual testing to exclude hearing or vision problems.6 Symptoms of comorbidities themselves may also overlap with the symptoms of other comorbidities, adding to the complexity of diagnosis.6

8. Offer Lifestyle Advice and Signpost to Support Groups

There are several useful strategies to implement during ‘watchful waiting’ or after a referral is made while waiting for an appointment, and for those with symptoms that do not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD.

Lifestyle Advice

Encourage regular exercise and a balanced diet.4 Offer referral to a dietitian if there appears to be a clear link between specific foods or drinks and hyperactivity.4 Fatty acid supplements, ‘few food’ diets, or elimination of artificial colouring and additives are not recommended treatments for ADHD.4

Offer advice to families and carers about maintaining positive interactions with CYP with ADHD, structure in daily activities, clear and appropriate rules about behaviour, and consistent management.4

Refer for ADHD-focused Group Parent Training

ADHD-focused group parent training can be offered without an ADHD diagnosis to parents/carers of CYP whose symptoms are suggestive of ADHD and adversely impact the person’s development or family life.4 This entails education about the causes and potential impacts of ADHD, and offers advice on parenting strategies. Reassure parents/carers that this does not imply bad parenting; the aim is to optimise parenting skills to meet the above-average parenting needs of CYP with ADHD.4

This is the first-line option for parents/carers of children aged under 5 years with suspected ADHD.4

Signpost to Local and National Support Groups

Parents, carers, and young people can access self-help and support groups online, which offer practical advice to implement at home and resources covering a wide range of topics, including parenting tips, education, disability allowance, driving, and employment. Some examples of helpful support groups can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: ADHD Information and Support Groups

| Organisation | Services |

|---|---|

| ADHD Foundation www.adhdfoundation.org.uk | Information and support for parents and carers including tips on behaviour management and information for UK professionals |

ADDISS Email: info@addiss.co.uk Phone: 020 8952 2800 | Information and resources for parents and carers, children and young people, teachers, and professionals |

| Young Minds www.youngminds.org.uk | Accessible information for young people with ADHD and signposts to further support and support for siblings. Includes a section for parents and carers with tips on behavioural strategies and self-care, and a parent/carer helpline |

| Contact www.contact.org.uk | Information and support for families including advice about education, benefits, social care, and local support |

| NHS website www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd | Includes information about medication and side effects, parenting tips, and coping strategies |

| ADHD=attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADDISS=Attention Deficit Disorder Information and Support Service | |

Specialist Interventions

There are also several nonpharmacological interventions available through specialist services.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation helps CYP with ADHD and their parents/carers to understand the condition and how it will affect their lives. Children with ADHD can be supported to anticipate developmental challenges as they enter adolescence and young adulthood,14 including the increased risk of substance misuse and self-medication, and possible effect on driving.4

Environmental Modifications

Specialists may advise schools or colleges to consider reasonable adjustments and environmental modifications, including seating arrangements, written instructions, laptops, extra time in exams, headphones, frequent movement breaks, and teaching assistant support.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Young people with ADHD who benefit from medication but have persisting significant impairment can be offered cognitive behavioural therapy. This aims to address social skills with peers, problem solving, self-control, how to deal with and express feelings, and active listening skills.4

9. Be Aware that Medications Offer a Good Balance of Benefits and Costs

Medications should be initiated by a specialist, and may help to create a window of opportunity for nonpharmacological strategies to work. They offer a better balance of benefits and costs than nonpharmacological interventions,4 shown across several long-term outcomes, including academic success, antisocial behaviour, driving, substance misuse, obesity, employment, self-esteem, and social function.15 ADHD medication can also reduce the risk of reoffending in adults by approximately one-third.16

Stimulant medications (for example methylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine, and dexamfetamine) work within minutes, and are effective in up to 85% of individuals to reduce ADHD symptoms and improve function. Prolonged use does not increase risk of addiction and may actually reduce it.6

Nonstimulants (atomoxetine, guanfacine) require several weeks’ use for the full effect.6

In CYP aged 5 years or older, methylphenidate is offered first line, with lisdexamfetamine offered to those who do not derive sufficient benefit after a 6-week trial of methylphenidate.4 Dexamfetamine, atomoxetine, or guanfacine are third-line options, and tertiary services may offer other medications, such as clonidine for coexisting tics and insomnia, and atypical antipsychotics for coexisting ODD.4

Note that use of medicines for treating ADHD is off-label in children aged 5 years.4

Encourage parents/carers to oversee compliance with ADHD medication, and suggest that patients take it as part of a daily routine, for example after brushing teeth, or using visual reminders such as apps and alarms.4

Try to address misconceptions about ADHD medication—for example, provide reassurance that it does not change the patient’s personality.4

10. Monitor Side Effects, Adherence, and Risk of Misuse

Prescribing and monitoring of ADHD medication are usually carried out under shared care protocol arrangements with primary care once the medication dose has been stabilised.4

Prescribing

As preparations can vary in bioavailability, prescribe the brand initiated by the specialist. The specialist should review medication at least once a year.4

Monitoring of ADHD Medication

Along with medication effectiveness, sleep pattern, adherence, and diversion risk, monitor:4

- height—6-monthly

- weight

- 3-monthly in children aged 10 years and under

- 3 and 6 months after treatment starts, then 6-monthly in children and young people aged over 10 years

- Heart rate and blood pressure—before and after each dose change, and 6-monthly

- Side effects, such as headache, anxiety, sleep problems, decreased appetite, arrhythmia, and tics.

Discuss any concerns, such as worsening behaviour, seizures, or sexual dysfunction with the specialist, and stop ADHD medication if psychosis or mania occurs.4 A planned break in treatment may be considered over the school holidays to allow ‘catch up’ growth if an individual’s height is causing concern.4

If weight loss is of clinical concern, advise those with a poor appetite to take medication after food and to add snacks in the early morning or late evening when medication effects are lowest.4 Referral to a dietician for advice about increasing healthy high-calorie food intake may help.4

Sleep hygiene techniques are a good starting point for those with sleep problems. These can be exacerbated by stimulant medications, and specialists may initiate adjuvant medications, such as melatonin and clonidine.

Risk of stimulant diversion and misuse can be reduced by prescribing long-acting preparations and keeping close track of prescriptions.6,17 Atomoxetine has low abuse potential and may be preferred for young people or families with potential for substance misuse or abuse.18

Summary

ADHD is a common disorder where persistent inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity lead to developmental and functional impairments, which may continue into adulthood. Early identification and appropriate referral can greatly improve long-term outcomes for those with significant impairment of day-to-day life.

The symptoms of ADHD can be easily missed in children and young people or confused with other conditions, such as ODD and autistic spectrum disorder. ADHD is more prevalent in certain high-risk groups, such as those born preterm, looked after children and young people, and those with a family history of ADHD. Girls with ADHD commonly present with inattentiveness symptoms, and ADHD should be considered in girls diagnosed with other mental health conditions.

It is helpful to offer lifestyle advice and signpost parents, carers, and young people to support groups. ADHD-focused group support helps parents and carers to optimise their parenting skills to meet the above-average needs of a child with ADHD. Although secondary care specialists diagnose ADHD and initiate ADHD medication, prescribing and monitoring of medication is usually carried out in primary care under shared care arrangements.

There is, however, wide variability in service provision, and there is an ongoing need for seamless transition of care into adult ADHD services for young people approaching 18 years of age.

Dr Natasha Halliwell

GP with ADHD tertiary care experience, Guildford

| At the time of publication (July 2021), some of the drugs discussed in this article did not have UK marketing authorisation for the indications discussed. Prescribers should refer to the individual summaries of product characteristics for further information and recommendations regarding the use of pharmacological therapies. For off-licence use of medicines, the prescriber should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for the decision. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information. |