Dr Emma Dickson Explores the Range of Possible Impacts Tinnitus Can Have on Individuals and Outlines NICE Guidance on Assessing and Managing this Common Condition

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

Tinnitus is the perception of sounds in the ear or head that does not come from an external source. These sounds can include ringing, hissing, humming, buzzing, whistling, sizzling, and even musical tinnitus. Tinnitus is a common condition that will affect 10% of people at some point in their life.1–3 Its impact varies and can range from being moderately annoying to disrupting a person’s ability to live a normal life. Tinnitus can affect concentration and result in insomnia, isolation, anxiety, depression, and even suicide.1,2,4

Types and Causes of Tinnitus

Tinnitus can be classified as subjective tinnitus, whereby the sound can only be heard by the individual, or objective tinnitus, which affects approximately 1% of people and can be heard by the individual and the examiner. Subjective tinnitus is the more common type.1

There are many reasons why tinnitus occurs, as outlined in NICE’s Clinical Knowledge Summary on tinnitus and summarised here in Table 1.1

Table 1: Causes of Tinnitus1

| Type | Cause | Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing loss (most common) | Age-related (common), noise-induced, Meniere’s, impacted wax, and otosclerosis (rare) | |

| Ear | Infections, including otitis media, and otitis externa | |

| Ototoxic medications | Valproate, cytotoxic drugs, loop diuretics such as furosemide and bumetanide, anti-inflammatories such as aspirin and NSAIDs, antimalarials such as quinine and chloroquine, antibiotics such as tetracyclines, macrolides, and aminoglycosides | |

| Neurological | Acoustic neuroma and multiple sclerosis | |

| Metabolic | Thyroid disorders, diabetes, lipid disorders, and zinc deficiency | |

| Psychological | Anxiety and depression | |

| Mechanical | Trauma of the head or neck and temporomandibular joint disorders. | |

| Disorders that cause objective tinnitus | Vascular | Arteriovenous malformation, vascular tumours, carotid/vertebral artery stenosis, dissection, and aneurysm |

| High cardiac output states | Anaemia | |

| Patulous Eustachian tube | Post adenoidectomy and weight loss | |

| Myoclonus | Involuntary jerks of palatal or middle ear muscles. | |

| NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | ||

The Need for a Guideline

Primary care healthcare professionals are often the first point of contact for people with tinnitus; however, currently across the UK there is a lack of standardisation in tinnitus assessment, referral, and management.4 In March 2020, NICE published NICE Guideline (NG) 155 Tinnitus: assessment and management.4 This aims to improve care for all people (adults, children, and young people) with tinnitus, unless otherwise stated, by providing advice to healthcare professionals on the assessment, investigation, and management of tinnitus and also by offering advice on supporting people who are distressed by tinnitus. Tinnitus is often associated with hearing loss and as a result this guideline should be read together with NG98 on hearing loss in adults.5

This article summarises the key recommendations from NG155 and how they apply to primary care, including guidance on:

- support and information for people with tinnitus

- referring people with tinnitus

- assessing the impact of tinnitus using questionnaires

- investigations

- management of tinnitus.

Assessment

NICE Guideline 155 does not include recommendations on clinical history or examination for assessment of tinnitus in primary care. The guideline committee has made a recommendation for further research in this area to determine optimal methods for assessing tinnitus in primary care, including key questions, physical examinations, and questionnaires.4

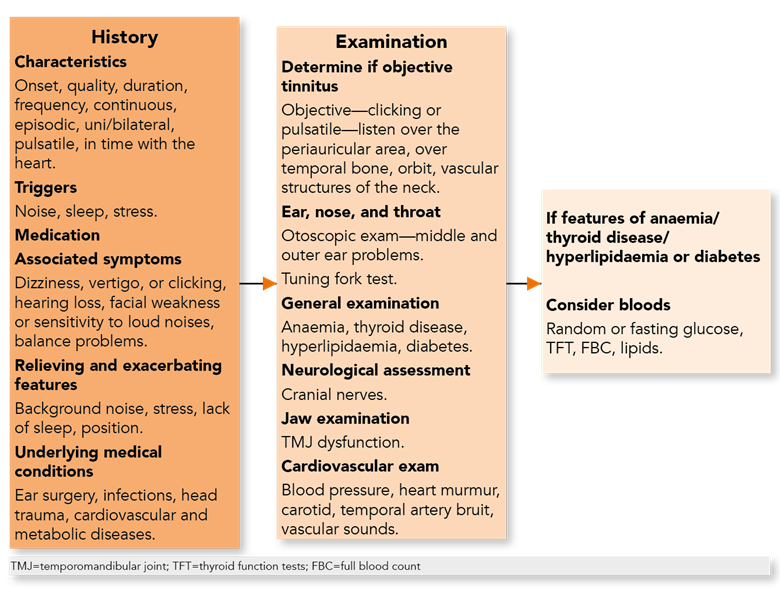

For the benefit of the primary healthcare practitioner, however, this article would not be complete without a reminder of current best practice in assessing tinnitus in day-to-day practice. A summary drawn from the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on tinnitus1 is therefore provided here on key history taking, examination, and investigation, which aims to uncover potential causes (see Figure 1).

Support and Information for People with Tinnitus

One of the key recommendations from NG155 is the importance of providing tinnitus support and information at all stages of care.Tinnitus support4 is clearly defined by the guideline committee as:

‘… a 2-way process of information-giving and discussion to help the healthcare professional understand the difficulties and goals of the person with tinnitus. This discussion occurs between the person with tinnitus, and their family members or carers if appropriate, and the healthcare professional. A management plan is also jointly developed and the person is supported to continue with the plan or modify it as necessary. This process is sometimes known as tinnitus counselling.’

The guideline recommends that this can be provided by:4

- discussing with the person with tinnitus, and their family members or carers if appropriate, their experience of tinnitus, including its impact and any concerns

- identifying needs and agreeing a management plan with the person, taking into account their preferences. The plan should include information about tinnitus and opportunities for discussion about different management options

- discussing with the person the results of any recent assessments and their impact on the management plan

- sharing the management plan with relevant health, education, and social care professionals. This should be done with consent from the person or their parent or carer, as appropriate.

There are times in primary care when people with tinnitus can delay accessing care. It is important when this occurs to ask the patient key questions, for example about lifestyle factors or changes in health, in order to understand the reason for the delay in access to care and why they are accessing care now.

Tinnitus Information

Giving information is a crucial element of the job as a healthcare professional and an essential element of good tinnitus care. NG155 highlights that the provision of information is an important part of tinnitus care and recommends providing the following key information at first point of contact to reassure the person:4

- tinnitus is a common condition

- it may resolve itself

- it is commonly associated with hearing loss. It is not commonly associated with other underlying physical problems

- there are a variety of management strategies to help people live well with tinnitus.

It is important that information is tailored to the individual needs of the person, and their family members or carers if appropriate. The information provided should include:4

- what tinnitus is, what might have caused it, what might happen in the future

- what can make tinnitus worse, for example stress, exposure to loud noise

- safe listening practices, for example noise protection

- impact of tinnitus (for example, it can affect sleep)

- investigations

- self-help and coping strategies, for example self-help books, relaxation strategies

- management options

- local and national support groups

- other sources of information.

NG155 does not make recommendations about any specific sources of information; for the primary healthcare professional, however, suitable voluntary resources that may be helpful include the British Tinnitus Association6 or Action on Hearing Loss.7

Referring People with Tinnitus

The intended outcome from the recommendations in NG155 about referrals is that appropriate intervention will reduce distress and repeated requests for referrals.4

In the guideline, referral of people presenting with tinnitus is either:

- immediate (NICE defines this as ‘to be seen by the specialist service within a few hours, or even more quickly if necessary’) or

- urgent (to be seen within 2 weeks), or

- non-urgent (where the timescale is not considered immediate or urgent).

Assessment and management of a person with tinnitus may still need to continue following an immediate referral.4 Table 2 provides up-to-date guidance4 on who should be referred and within what timescale.

It is important to note there were no recommendations made in NG155 about where these referrals should be made to, due to the variation in pathways throughout the UK.

The recommendations for referrals for persistent pulsatile tinnitus and persistent unilateral tinnitus were made in line with the NICE guideline on hearing loss in adults.4,5 The committee noted that these types of tinnitus can be associated with vascular or neurological abnormalities. Onward referral for further investigations to detect these abnormalities may prevent the development of significant pathologies such as vestibular schwannoma.4

Table 2: Referring People with Tinnitus4

| Time Scale | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Immediate | Within a few hours—patient ‘to be seen by the specialist service within a few hours, or even more quickly if necessary’4

Within 24 hours—patient ‘to be seen within 24 hours’4

|

Urgent | Within 2 weeks—patient ‘to be seen within 2 weeks for assessment and management’4

|

| Non-urgent | Patient to be referred ‘for tinnitus assessment and management in line with local pathways’4

|

Assessing the Impact of Tinnitus

Assessing the Impact Using Questionnaires

In primary care it is not currently common practice to use questionnaires to assess how tinnitus affects a person; in secondary care, however, the Tinnitus Functional Index is used to provide a broad assessment of the impact of tinnitus and NICE recommends that practitioners consider using this as an evaluation tool for adults.4 The use of a visual analogue scale is a suitable alternative when questionnaires are not suitable to assess how tinnitus affects a person.4 The following key questions can also be used to assess the impact of tinnitus:

- how much does the tinnitus bother you?

- how much does the tinnitus interfere with what you do?

The guideline committee felt there was a need for further research into examining the optimal method for assessing tinnitus in general practice to help inform management.4

Assessing How the Tinnitus Affects Quality of Life

As is often the case with those presenting with medical problems, people with tinnitus tend to seek help when the condition affects their quality of life. The guideline recommends that during history taking and discussion it is important to discuss the impact of tinnitus on home, social, leisure, work, and school so that this can help shape the clinical management plan.4

Assessing How Tinnitus Affects Sleep

Insomnia is common in people with tinnitus and can have a psychological impact. The guideline recommends asking patients whether they have problems sleeping because of tinnitus and that practitioners should consider the use of a questionnaire (such as the Insomnia Severity Index) to understand the effect tinnitus has on the patient if sleep is affected. Understanding and addressing this issue in primary care may have impact on those with tinnitus and be useful when developing a management plan with them.

Assessing the Psychological Impact

Tinnitus is known to cause depression and anxiety and can exacerbate the symptoms of anxiety and depression. As a part of the assessment of someone with tinnitus it is important to ask about anxiety and depression. The guideline recommends being alert at all stages to the impact of tinnitus on mental health.4

Where there are concerns in adults, assessment should be considered using the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation—Outcome Measure10 or by following recommendations on assessment in the NICE guideline on common mental health problems.11 Use of the tinnitus questionnaire (TQ) and/or mini TQ alongside the Tinnitus Functional Index can be considered in adults if further psychological evaluation is needed.4 These are commonly used in tinnitus-specific services and there are no current specific recommendations for them to be used in primary care.

If a mental health problem is diagnosed, an action plan should be put in place in line with the recommendations on assessment in the NICE guideline on common mental health problems.11

Children and young people should be assessed and managed in line with the NICE guideline on depression in children and young people.4,12

Investigations

Primary care access to investigations for tinnitus is variable throughout the UK. Some healthcare practitioners working in these areas may have access to in-house audiological assessment but for most, onward referral is required. It is important for the healthcare practitioner to understand what investigations may happen on referral so that they can inform the person with tinnitus. When onward referral for a person with tinnitus is made to ear, nose, and throat (ENT), audiology, or audiovestibular medicine, the guideline recommends an audiological assessment. It is known that hearing loss commonly coexists with tinnitus and can go undetected. If the audiometric assessment identifies suspicion of middle ear or Eustachian tube dysfunction or other causes of conductive hearing loss are suspected, tympanometry may be considered.4

While GPs are often not involved in organising imaging for people with tinnitus, it is important to understand when imaging may be offered. First line is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), while computed tomography (CT) may be offered for those who are unable to have an MRI. Table 3 gives guidance on which people with tinnitus would be referred for imaging.

Table 3: Imaging for Tinnitus4

| Tinnitus Characteristics | Imaging Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-pulsatile tinnitus | Non-pulsatile tinnitus with neurological, otological, or head and neck signs and symptoms | Offer MRI (IAM) or contrast-enhanced CT (IAM) |

| Unilateral or asymmetrical non-pulsatile tinnitus with no associated neurological, audiological, otological, or head and neck signs and symptoms | Consider MRI (IAM) or contrast-enhanced CT (IAM) | |

| Pulsatile tinnitus | Synchronous pulsatile tinnitus if clinical examination and audiological assessment are normal | Consider magnetic resonance angiogram or MRI of head, neck, temporal bone, and IAM or contrast-enhanced CT of head, neck, temporal bone, and IAM |

| Pulsatile tinnitus if an osseous or middle-ear abnormality is suspected (e.g., glomus tumour) | Consider contrast-enhanced CT of temporal bone followed by MRI if further investigation of soft tissue is required | |

| Non-synchronous pulsatile tinnitus (e.g. caused by palatal myoclonus) | Consider MRI of the head, or if they cannot have MRI, contrast-enhanced CT of the head. | |

| MRI=magnetic resonance imaging; IAM=internal auditory meati; CT=computed tomography | ||

Management of Tinnitus

There are no medications that currently help in the management of tinnitus. While betahistine is licensed for the management of Meniere’s disease, of which tinnitus is a symptom, the evidence suggests it does not improve symptoms and should not be offered for management of tinnitus. There is evidence it may cause adverse effects.4 Current guidance recommends the use of amplification devices and/or psychological therapies for persons with tinnitus.4

Amplification devices are recommended for people with tinnitus who have a hearing loss that affects their ability to communicate.4,5 If a person with tinnitus has a hearing loss but no communication issues, an amplification device should be considered.4

Psychological therapies are recommended for people with tinnitus-related distress. The evidence suggests benefit from psychological therapies for tinnitus. For adults whose distress from tinnitus continues to impact on their emotional and social wellbeing, consider providing psychological therapies in a stepped manner in the following order:4

- digital tinnitus-related cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) provided by psychologists

- group-based tinnitus-related psychological interventions including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (delivered by appropriately trained and supervised practitioners), acceptance and commitment therapy or CBT (delivered by psychologists)

- individual tinnitus-related CBT (delivered by psychologists).

Evidence for and access to psychological therapies for children and young people is limited. In preparing NG155, no evidence was identified that evaluated psychological therapies in children and young people, and as a result, the committee made a recommendation for further research in this area.4

Summary

The NICE guideline discussed in this article provides recommendations to improve care for people with tinnitus by providing advice to healthcare professionals on the assessment, investigation, and management of tinnitus. It also offers advice on supporting people who are distressed by tinnitus, and on when to refer for further assessment and management. The overarching aim is for the healthcare professional to provide standardised high-quality tinnitus care from the first point of contact in order to help people manage their tinnitus and/or the impact of their tinnitus. Providing information and support at all stages of care is key. Referring people with tinnitus to specialist services in line with NG155 will reduce distress and repeated requests for referrals. It is important to assess the impact of tinnitus on a person, their quality of life, and how tinnitus affects their sleep, as well as any psychological impact. Investigations and management are tailored to the individual and amplification devices and psychological therapies are recommended as possible options for management.

Dr Emma Dickson

GP with a special interest in ENT, Northern Ireland

Member of the NG155 guideline development group

The guideline referred to in this article was produced by the National Guideline Centre for NICE. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of NICE. NICE. Tinnitus: assessment and management. NICE, 2020. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng155 |

| Key Points |

|---|

|

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system |