Dr Maggie Keeble Offers 10 Top Tips on Providing Personalised, Holistic Care for People Living with Frailty at the End of Their Lives

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

The specialty of palliative medicine arose from the work of the pioneers of the UK hospice movement in the 1950s.1 In the UK, palliative medicine became a subspecialty of general medicine in the 1980s, and a specialty in its own right in the 1990s, with associated training roles and its own journal.2 The specialty focuses on providing compassionate, holistic ‘care of the dying’;1 however, this narrow focus risks excluding people with frailty, who can exist in a state of susceptibility to acute deterioration for weeks, months, or even years.

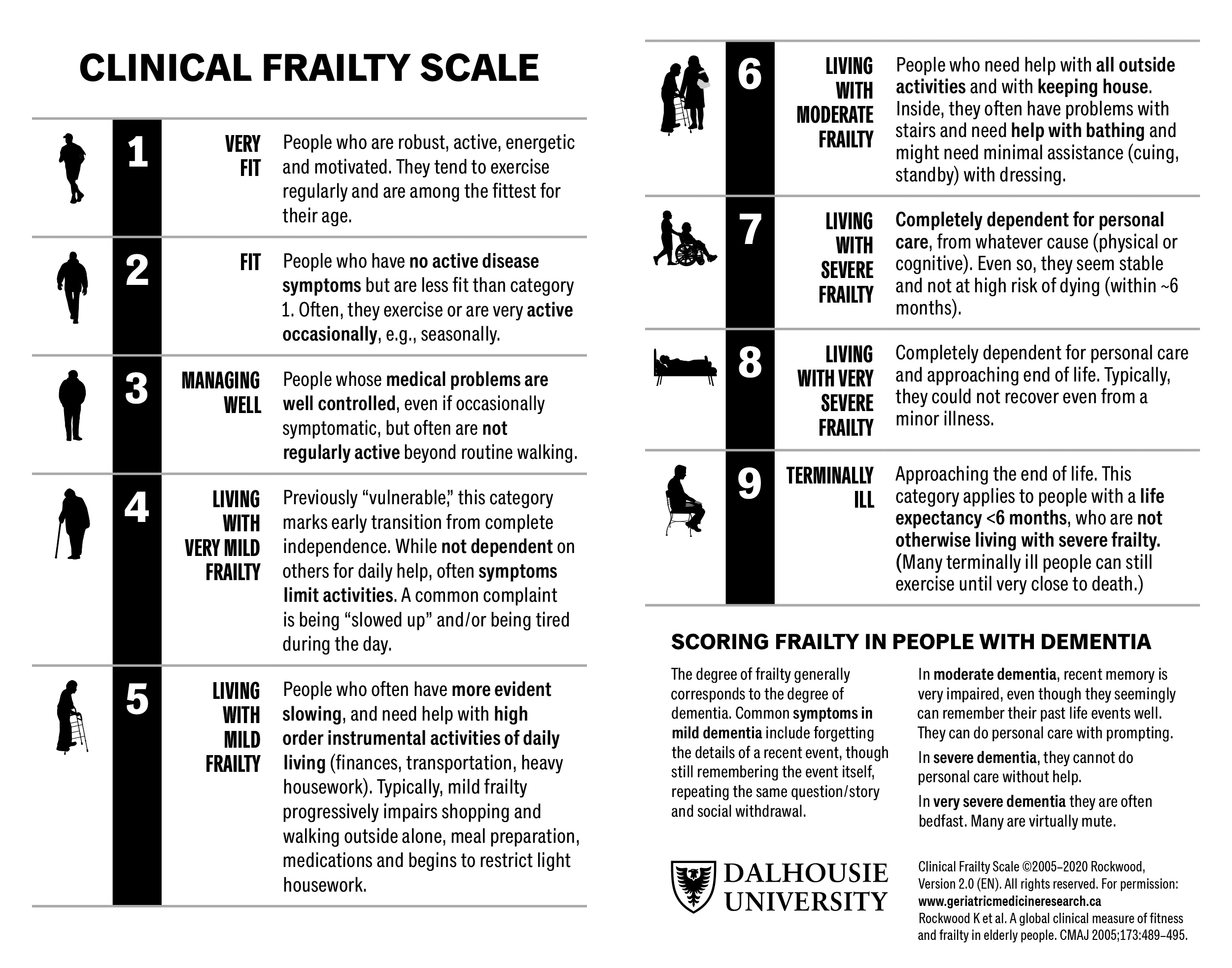

Changes in lifestyle, immunisation, and medical treatment have led to increased life expectancy, in turn swelling the population of people living with frailty. Clinical frailty is a syndrome characterised by vulnerability to sudden deterioration, and is as distinct from the descriptive term ‘frail’ as clinical depression is from feeling ‘depressed’. It is rarely seen in people aged less than 65 years, and although it can overlap with physical disabilities and comorbidities, it is a distinct condition. Clinical frailty can be diagnosed using tools such as the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS; see Figure 1)3,4 and the Edmonton Frail Scale.5 Mild frailty correlates with a CFS score of 5, moderate frailty with a score of 6, and severe frailty with scores of 7, 8, or 9. For the remainder of this article, the term ‘frailty’ implies the syndrome of clinical frailty.

© Dalhousie University

Reproduced with permission

1. Understand that Dying with Clinical Frailty is Different from Dying with Cancer

Traditionally, end of life and palliative care services have focused on people dying with cancer, for whom good-quality care is based on a predictable course of decline. It is important to understand that people dying with frailty do not die in the same manner as those dying with cancer. The trajectories are different, the time scales are much less predictable, and the approach of death is much less obvious.6 Although death is inevitable, its timing in people living with frailty is uncertain.

2. Recognise that the Usual Rules and Frameworks Don’t Apply

Traditional definitions of end of life define this period as the last 12 months of life, and current General Medical Council guidance indicates that patients should be considered to be approaching the end of their lives if they have ‘general frailty and co-existing conditions that mean they are expected to die within 12 months’.7 Similarly, when compiling end of life and palliative care registers, clinicians are advised to use the ‘surprise question’—‘Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?’— to determine eligibility.8 If they would not be surprised, then the patient should be included on the register.

In a situation where no single condition predominates and frailty is evident, this 12-month cutoff is inappropriate, and the ‘surprise question’ was found to perform ‘poorly to modestly’ as a predictive tool for death.8 People living with a significant degree of clinical frailty can experience acute exacerbations characterised by rapid-onset or worsening confusion (delirium), sudden deterioration in mobility, and an increased rate of falls. The causes of an acute deterioration in frailty are myriad, and include infection, dehydration, constipation, and electrolyte imbalance.

Uncertain Recovery

During an acute deterioration, people with frailty may look very unwell and become ill enough to die, but they can recover and restabilise for weeks, months, or even years. Anyone working regularly with people living with frailty will recognise the experience of being convinced that someone is going to die, only to come back the next day to find them much improved. It’s not the clinician ‘getting it wrong’, but a recognisable pattern of recovery in frailty.

The phrase ‘uncertain recovery’, first used as part of the Amber Care Bundle,9 is incredibly useful when liaising with relatives and other clinicians because it enables a dichotomous approach of ‘hoping for the best while preparing for the worst’. It is helpful to be explicit about the uncertainty. I often use the phrase ‘we are entering a twilight zone’ to describe the period of about 72 hours when things could go either way. Warning family members that someone may die in the next few days, but that you can’t be sure, enables people to travel from a distance if necessary and see their relative before they die. If they then recover, it’s a win–win situation: the family have had an opportunity to gather, you and the team may be seen as having ‘saved the person’s life’, and it’s an ideal chance to talk with the patient and/or their advocates about actions to be taken when, not if, this happens again. It is certain that a further episode of deterioration will occur before long.

At the other extreme, a person living with frailty may deteriorate very suddenly after a long period of stability, and die within 24–48 hours. This may take clinicians and family members by surprise, even if the person is known to be living with frailty. Using narrow parameters to identify a cohort of patients living with frailty who are ‘likely to die within the next 12 months’ is therefore impossible and unhelpful. It effectively excludes people who are living with frailty from being offered the opportunity to discuss their wishes and preferences; this is increasingly the norm for people dying with cancer.

Lack of Financial Support

Funding is usually available from the NHS to support end of life care for people dying of cancer who meet the eligibility criteria of sufficient primary health need and a rapidly deteriorating condition leading to a terminal phase.10 This Continuing Health Care (CHC) funding is rarely available to people with frailty. In order to qualify, there must be a specific requirement for either high-level physical or mental healthcare (as opposed to social support and accommodation), or a state of rapid and predictable deterioration. This is often not the case for people living with frailty. If someone is living with frailty and/or mild-to-moderate dementia, either in their own home or in a care home but without nursing, they are unlikely to meet the threshold for CHC funding. A sudden, acute episode and deterioration in a person with frailty followed by a period of uncertain recovery may prompt a request for CHC funding, but their recovery and restabilisation will mean that they are no longer eligible for financial support, even though they appeared to be close to death.

3. Avoid Labels and Pathways, and Embrace a Palliative Approach

In England, the average life expectancy is 79.3 years for men and 83.1 years for women.11 Although the timing of the last days of life is unpredictable, there is no escaping the fact that anyone aged more than 80 years is approaching the end of their lives. Some people may not want to accept that they are going to die in the not-too-distant future, but the fact that they are coming towards the end of their life is indisputable, even if they go on to live for another 10 years. Changing our language and highlighting the inevitable enables individuals and their clinicians to recognise that the end of life is approaching. Conversations about this subject are therefore appropriate for anyone aged older than 80 years, irrespective of whether they are living with frailty, but everyone should be encouraged to consider their own mortality with a view to making the most of their lives.

Understand Patients’ Preferences

Having acknowledged that the end of life is approaching, and taken the opportunity to discuss their priorities and wishes, some people living with frailty may decide that they do not want to undergo certain interventions. This decision, made by the person with frailty or on their behalf by an advocate, enables clinicians to adopt a ‘palliative approach to care’, avoiding certain interventions (such as resuscitation or hospital admission) but continuing to offer wanted and appropriate interventions (such as antibiotics or subcutaneous fluids). Other people living with the same degree of frailty may make a different decision, and want all appropriate interventions to be undertaken, including admission, but may draw the line at intensive care.

Avoid Labels and Pathways

Labelling someone as ‘an end of life patient’ or ‘a palliative patient’ may result in failure to offer entirely appropriate interventions, such as hospital admission or administration of subcutaneous fluids, when the aim of the intervention is to improve comfort. Examples include withdrawal of nutrition or hydration by drip or tube without explanation or consultation, or denial of oral fluids to patients who are able to swallow without serious risk of choking or aspiration.12

An ‘end of life pathway’ is a one-size-fits-all process. Pathway-driven care, determined by the degree of frailty or by labels such as ‘palliative patient’ or ‘end of life patient’, prohibits patient choice and should be avoided. Lack of flexibility, failure to recognise uncertain recovery in noncancer situations, and the inability to respond to a nuanced situation or personal preferences risks inappropriate and potentially harmful outcomes, as demonstrated by the storm surrounding the well-intentioned Liverpool Care Pathway.12

Adopting a palliative approach to care and avoiding labels and pathways facilitates discussion and shared decision making with the person and/or their advocate.

4. Master the Building Blocks of Good-quality End of Life Care

The Gold Standard Framework,13 RCGP Daffodil Standards,14 and similar high-quality initiatives highlight the importance of a set of building blocks that, if used routinely, can enhance the quality of end of life and palliative care. Examples of these building blocks are provided in Box 1. These steps are identical when dealing with someone living with frailty. The first step is always to recognise that someone is approaching the end of their life. With a cancer-related illness, there are often clear triggers for recognition, such as a dramatic diagnosis, recurrent or metastatic disease, or failure of treatment. In a situation where frailty is the underlying cause of decline, if the approach of the end of life isn’t recognised and the person isn’t identified as being at risk, then subsequent steps on the path to quality end of life care don’t happen, and opportunities for discussions and making plans are missed.15

| Box 1: Building Blocks of Quality End of Life and Palliative Care |

|---|

|

5. Identify When End of Life is Approaching in Patients with Frailty

There are three useful markers that can help to identify when a person with frailty is approaching the end of their life:

- degree of clinical frailty

- extreme old age

- hospital admission in patients aged more than 85 years.

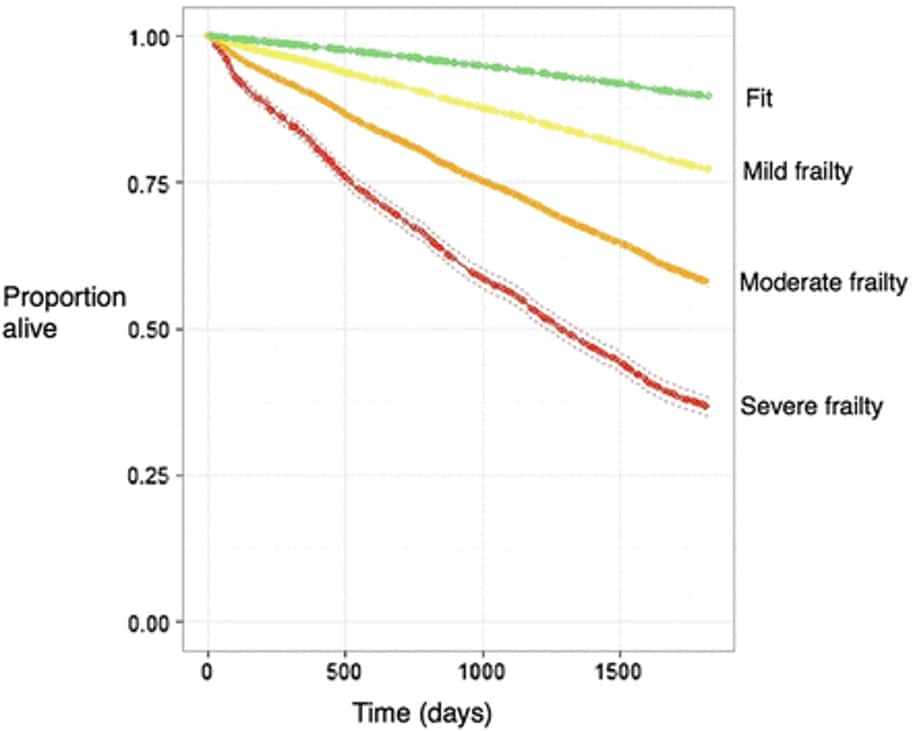

The more severe someone’s frailty, the more likely they are to die. The Electronic Frailty Index (eFI) is a useful screening tool to identify people at risk of clinical frailty.16 Analysis of populations using this risk scoring system has demonstrated that risk score and mortality are closely related (see Figure 2).16 Someone with an eFI indicating severe frailty has an average life expectancy of 3.5 years, regardless of their age.16 Anyone living with severe frailty should be considered as approaching the end of their life, and offered the opportunity to discuss their wishes and preferences about future care.

Five-year Kaplan–Meier survival curve for the outcome of mortality for categories of fit, mild frailty, moderate frailty, and severe frailty (internal validation cohort)eFI=electronic frailty indexClegg A, Bates C, Young J et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016; 45 (3): 353–360.

Reproduced with permission

Those living with moderate frailty at particular risk can be identified using additional measures, such as extreme old age (the average life expectancies of men and women aged 90 years are 4.02 years and 4.58 years, respectively),17 and one or more hospital admissions (in people aged more than 85 years, one or more admissions is associated with a mortality rate approaching 46% at 12 months).18 Additional warning signs include persistent and recurrent infections, episodes of delirium, weight loss of greater than 10% in 6 months, exacerbation of falling, and escalating patient, family, or service provider distress.15

6. Start Conversations About Advance Care Planning Early

A significant number of people living with frailty have acute or chronic cognitive impairment due to delirium or dementia. As a result, they may lack the mental capacity to make decisions about their care in the future. Knowing someone’s wishes and preferences in advance, and having legal advocates who are aware of them, enables a Best Interest Decision to be made for people who lack mental capacity as defined by the Mental Capacity Act.19 In addition, the delivery of appropriate care in an emergency becomes much more straightforward and less stressful if clinicians are working with this knowledge to hand. This re-emphasises the importance of early conversations about advance care planning, particularly when someone is known to be living with dementia.

Lasting Power of Attorney registrations are increasing, but all too often, even when these are in place, families haven’t had a conversation about what a person would want if they become unwell and are unable to decide for themselves. Families can be prompted to consider and discuss the options through the use of recognised online resources, such as those on the Compassion in Dying website around creating Advance Statements or Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment.20 Completion of a ReSPECT (Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment) form21 or DNACPR (do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation) order may be part of this discussion, or may come at some time in the future when all parties have had time to consider. Unless raised by healthcare professionals (HCPs), families may not be aware of their options, and may be reluctant to start the conversation. It is important for HCPs to understand the practical and legal aspects of advance care planning, and support families looking for advice. In my practice, the use of Care Coordinators to work with families has transformed the team’s ability to ensure that these conversations are held routinely on admission to a care home.

Although planning for a funeral is not uncommon, planning for the stage before death is very rare. Despite being fit and well at the current time and hoping to live for many more years, I already have an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment in place. In the words of Ira Byock, an American physician and advocate for palliative care: ‘I have an Advance Statement not because I have a chronic illness—I have an Advance Statement because I have a family.’ 22 It’s never too soon to think about it and discuss it—it’s going to happen to all of us, not just our patients.

7. Appreciate that Symptom Control has Different Focuses and Challenges in People with Frailty

The most common symptom experienced by people dying with cancer is pain, followed by breathlessness, nausea, and vomiting. The symptoms experienced by people dying with frailty may be less dramatic, but can be equally distressing. Constipation,23 delirium,24 and general weakness are the most common, but often go unrecognised and may therefore be poorly managed.

There are particular challenges when managing symptoms in people living with frailty:

- knowing what the symptoms are

- a high risk of side effects with medication

- problems with swallowing—‘can’t swallow’

- problems with compliance—‘won’t swallow’.

The Difficulty of Elucidating Symptoms and Signs

Pain may be poorly or uncharacteristically expressed by people living with frailty, particularly those with dementia. In these situations, use of a recognised tool, such as the Abbey Pain Scale,25 and a high index of suspicion are important to ensure that people don’t have pain that goes unrelieved. A trial of analgesia when pain is suspected is worth considering, taking into account the risks associated with analgesic medication.

Constipation may manifest as overflow diarrhoea or poor appetite. The only way to really assess whether someone has significant constipation is to examine them both abdominally and rectally.23 Failure to do so, or to adequately manage constipation with a range of laxatives, is a common reason for hospital admission.

Risk of Side Effects with Medication

Any medication administered for symptom control in frailty has a high chance of causing side effects, such as drowsiness, constipation, confusion, and an increased risk of falls. This applies in particular to analgesics, antihypertensives, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and any medication with anticholinergic effects.26 When prescribing any new medication, the risk–benefit ratio needs to be considered, and any potential risks explained to the patient, their family, and their carers. It is also worth reviewing the requirement for all nonessential medications (for example, anticoagulants and statins) to assess whether they are still appropriate or could be discontinued.

Problems with Swallowing

Swallowing is often impaired in the later stages of frailty and dementia for reasons such as general weakness, poor positioning, and impaired neuromuscular mechanisms. Aspiration is common, and a wet cough or frequent chest infections should alert clinicians to this possibility.27 Changing the texture of fluids by adding thickeners to drinks and taking medication with yoghurt or jam can improve the situation considerably, as can ensuring that the individual is as upright as possible while eating, drinking, and taking medication. When a patient is known to have a swallowing problem, the use of straws and lidded beakers should be discouraged because they increase the risk of aspiration. Liquid preparations can be useful, and subcutaneous injections or infusions of medication can be used when appropriate. Patches should be considered a last resort when swallowing is an issue, because drug levels are slow to accumulate and stabilise, and difficult to titrate. High-dose opioid patches, such as fentanyl patches, should not be used first line for older people living with frailty who are opioid naïve.

Problems with Compliance

Compliance with medication in long-term conditions is known to be low.28 There are particular challenges when cognition is impaired,29 such as when a person living with dementia refuses to take medication orally. Under these circumstances, a mental capacity assessment is required. If the individual is thought to retain capacity, and can understand the rationale for prescribing and the pros and cons of taking medication, then they have the right to refuse to take it. If, however, they are deemed not to have capacity, then it is important to consult the multidisciplinary team and health attorney(s) to consider which medications are essential and how they should be administered. Under these circumstances, a systematic medication review using a recognised tool (for example, the STOPP [screening tool of older people’s prescriptions] and START [screening tool to alert to right treatment] Criteria)30 can whittle down the medication burden to an absolute minimum. A Best Interest Decision needs to be recorded and, ideally, a Covert Administration of Medication document should be completed. Options for covert medication include application of patches for pain relief and/or liquid medication concealed in food or drinks. Low-dose 7-day patches may be useful when chronic pain is a problem and compliance an issue. To prevent the patch from being removed, it may be helpful to locate it on an area of skin that the patient can’t reach, such as between the shoulder blades. Pharmacist colleagues are particularly helpful when it comes to discussing and planning covert administration of medication.

8. Prescribe Anticipatory Medication

The uncertain and sudden nature of deterioration in frailty means that it is important to prescribe ‘just-in-case medication’ in a timely manner. Waiting until you think that the person has days or hours left to live will mean leaving it too late for many. An acute deterioration is much more likely to occur ‘out of hours’, when access to medication will be challenging and slow. Consider prescribing anticipatory medication routinely when discussing advance care planning in severe frailty, especially for those living in care homes. The standard quartet of analgesics, antiemetics, anxiolytics, and antisecretory medication should be prescribed—although, in my experience, the anxiolytics and antisecretory medications are those most commonly indicated.

Anyone with an Advance Care Plan that recommends maintaining the person in their home in the event of a deterioration, if symptoms can be controlled, should have anticipatory medication prescribed. When writing an administration chart for anticipatory medication, only prescribe individual doses of subcutaneous injections, which can be given quickly by nursing colleagues without consultation with a prescriber. It is important to prescribe low doses, particularly in opioid- and benzodiazepine-naïve patients. A syringe driver prescription can be written at a later stage, but having ready access to the medication enables a syringe driver to be sited in a timely manner when necessary. The cost of prescribing possibly unneeded medication is greatly outweighed by the emotional and financial gains of preventing an inappropriate and unwanted admission due to an inability to maintain comfort. The medication doesn’t need to be reissued until it approaches its use-by date. Care homes should have adequate facilities to store this medication for their residents, and robust controlled drug protocols.

9. Accept that Informal Carers are a Vital Part of the Team Around the Patient

No one knows the person living with frailty better than the partner, family member, or friend who is their main source of support. They may have known the individual for many years, and will be able to offer valuable insights into their personality, history, and current presentation. It is vital to get to know their opinions, which are usually—if not always—aligned with those of the patient. If a person lacks the mental capacity to make decisions, the informal carers or family will only have the legal authority to make Best Interests Decisions on their behalf if they have Lasting Power of Attorney for Health. If not, it is important that they are consulted by clinicians when making Best Interest Decisions. As already stated, Care Coordinators can be used to liaise directly with older people and their family members. They can gather information about past and more recent medical history, family, and social background, as well as introducing the topic of advance care planning.

10. Record Clinical Frailty as an Underlying Cause of Death

Dementia was the leading cause of death in the UK in 2018.31 In my opinion, this is because frailty is not accepted as a primary cause of death, whereas dementia is. Therefore, when someone living with dementia and frailty dies without any other obvious or single cause of death, dementia is selected as the cause. This masks the contribution that frailty is making to our changing mode of death. People living with frailty don’t tend to die of frailty, but with frailty. Coroners are, not unreasonably, unwilling to accept ‘old age’ or ‘frailty of old age’ as a primary cause of death, but suggest that frailty appears as a contributory factor, particularly when the primary cause is not usually fatal.32 When an older person living with frailty dies of an apparently treatable condition (for example, a chest infection or sepsis due to cellulitis), the addition of frailty as a contributory cause is particularly important—it helps to reassure family members that they weren’t let down by the system, and that the person died a natural death despite the care given. By recording clinical frailty as a contributing factor, its significance will become more obvious.

Summary

People living with frailty can exist in a state of vulnerability to acute deterioration for a long time, and are at risk of being excluded from good-quality end of life care as a result of narrow definitions of care for the dying. Better recognition and understanding of frailty, and the contribution it makes to cause of death, will enable a greater awareness of how best to support older people with frailty approaching the end of their lives.

| Key Points |

|---|

|

Dr Maggie Keeble

Care Home GP and Clinical Lead for Integrated Care for Older People, Worcester