Jemma Lough and the Guidelines in Practice Team Summarise the Findings of a Readership Survey on the State of General Practice, Which Reveal Significant Problems With Workload, Morale, and Primary Care Network Integration

| Read this Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find commentary on the results of the survey from Dr David Jenner at the end of this article. |

The NHS in England is undergoing a restructure intended to transform primary care, enhance connections between local health and care services, and tailor services to local population health needs.1–5 The reforms—which would have been challenging without COVID-19 becoming a priority for the health service—are being implemented at a time when the NHS is overburdened and under-resourced, and when healthcare professionals are also faced with managing the downstream impacts of COVID-19 on patients and on the health system as a whole.

The specifics of the restructure were initially laid out in January 2019, when the British Medical Association and NHS England published a 5-year proposal for GP contract reform,6 which was intended to realise the ambitions of the NHS Long Term Plan in part through the creation of primary care networks (PCNs).7 This intention was further developed in November 2020, when NHS England and NHS Improvement published Integrating care, which established plans for ‘stronger partnerships in local places between the NHS, local government and others with a more central role for primary care in providing joined-up care’.2

Last year, Guidelines in Practice invited its readers to share their views on the NHS reorganisation as it was being enacted (read the 2021 report at: bit.ly/3L1DPkM).8 Many respondents were concerned that the reforms were not going to deliver the intended improvements for healthcare professionals and patients, and were dismayed about the limited time and resources available for implementing change.8,9 There was some optimism, however, about the potential of the restructure to facilitate better and more efficient care for patients across primary, community, and secondary care.8,9

Many GP practices have now been working in PCNs for more than a year, with the aim of delivering the place-based population health strategies of integrated care systems at the primary care level.1–5 Guidelines in Practice conducted a survey in May 2022 to discover how its readers feel about the NHS restructure 1 year on, now that PCNs have evolved and the challenges and opportunities they present have become more apparent. For a breakdown of the respondents, see Box 1.

| Box 1: Breakdown of Survey Respondents by Sector and Role[A] |

|---|

Of the 366 healthcare professionals who responded to the survey:

Of the healthcare professionals surveyed:

[A] Respondents were allowed to skip questions, so the statistics reported in the article refer to the proportion of participants that answered each question AHP=allied health professional; PCN=primary care network |

This summary will focus on three key themes: workload, PCNs, and the future of primary care. A full report will be published online later in 2022.

Workforce and workload

Workforce Shortages and Overwork

Workforce shortages and their impact are central to the findings. Respondents said that unfilled vacancies are widespread, with 64.0% reporting vacancies within their primary care team. These vacancies are predominantly in clinical roles (46.8%), but in many cases affect a combination of clinical, administrative, and Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme posts (44.2%). Participants overwhelmingly believed that these unfilled roles will have a negative impact on:

- team morale (89.7%)

- patient care (84.9%)

- achievement of Quality and Outcomes Framework targets (83.7%)

- clearance of the care backlog generated by the pandemic (79.9%)

More than half also thought that they will affect PCN development (60.6%).

… unfilled vacancies are widespread, with 64.0% reporting vacancies within their primary care team

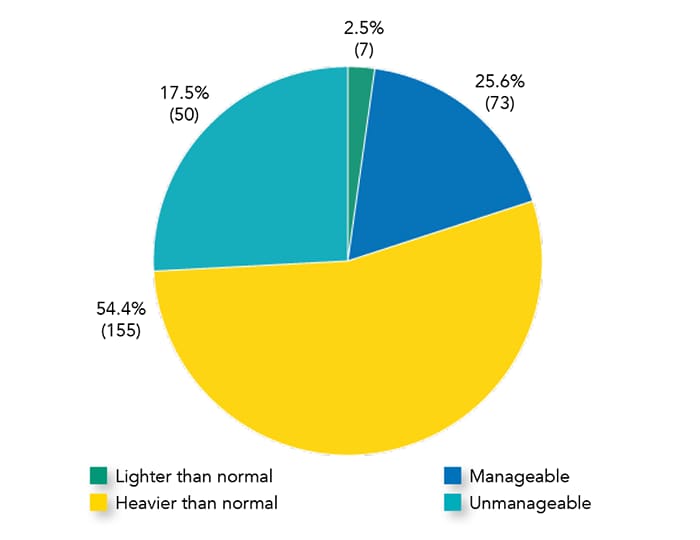

Unfilled vacancies have likely contributed to the workload pressures faced by healthcare professionals currently working in primary care (see Figure 1). Notably, 80.0% of respondents—and 87.6% of participants who are doctors—reported a heavier burden than normal over the past year. Of these, 41.6% of doctors and 25.6% of all respondents said that their workload was unmanageable. This means that, last year, two in every five doctors experienced an unsustainable workload. Furthermore, there was little optimism about workloads improving in future: only 3.2% of those surveyed anticipated that this will reduce, with 20.7% believing that it will stay the same, and 76.1% saying that it is likely to get heavier.

... 80.0% of respondents—and 87.6% of participants who are doctors—reported a heavier workload than normal over the past year

Measures for Managing Workload

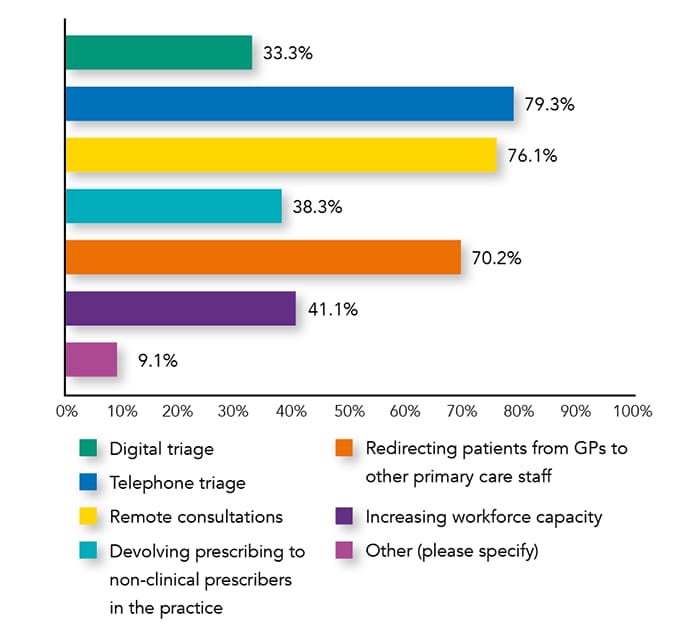

A variety of measures are being used in practices to manage excessive workloads (see Figure 2); the use of some was accelerated during the pandemic and has been retained as the NHS tackles the care backlog. Respondents were, however, equivocal about the effectiveness of these measures. Around two-thirds (60–66%) felt that increasing workforce capacity, devolving prescribing to nonclinical prescribers in the practice, and redirecting patients from GPs to other primary care staff were successful in reducing their workload, whereas relatively fewer (59.4% and 50.0%, respectively) believed that remote consultations and digital triage achieved this.

Clearly, many respondents do not feel that these measures are helping to lighten their workload. For alternative measures suggested by respondents and participants’ reactions to this question, see Box 2.

| Box 2: Suggestions From Respondents for Managing Workload |

|---|

Alternative Measures Volunteered by Respondents ‘ARRS’ ‘Allied health professionals’ ‘Community mobile clinic’ ‘Better organisation of clinics to make the patient journey more efficient and effective, giving the nursing team more time to see different patients and to keep on top of the workload … [resulting in] happier patients and nursing staff, less complaints, [and] less time-wasting’ ‘Direct patients to local pharmacy’ ‘GP+’ ‘Common ailments scheme’ Reactions to Current Measures for Managing Workload ‘They do not appear to be managing it at all’ ‘Would like to recruit, but lack funds and staff with experience; more staff plan to leave’ ‘Expect current staff to work harder’ ‘Whatever we do, there [are] not enough people to work. Politicians are increasingly increasing the expectation[s] of patient[s] without funds’ ‘I work in urgent care where we receive patients from GP surgeries. We may have to send patients to other UTCs or A&E or book to return next day’ ARRS=Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme; UTC=urgent treatment centre; A&E=accident and emergency |

Interestingly, more respondents said that these measures improved patient care (63.9%) than were effective for managing workload (60.9%). Between 60% and 71% of the participants agreed that patient care was improved by any of the measures—except for digital triage, for which the figure was only 53.1%.

Staff Retention and Changing Role

In the context of this increased workload, almost half of those surveyed (47.0% of all respondents and 49.1% of doctors) said that they plan to change their role within the next 2 years. Of these, 17.5% will reduce their hours (25.0% of doctors), 13.4% plan to retire (11.1% of doctors), 10.7% hope to move roles within primary care (9.3% of doctors), and 5.5% intend to leave general practice (3.7% of doctors).

In a recent Royal College of General Practitioners survey, 19% of GP and trainee respondents stated that they were likely to leave the profession in the next 2 years, increasing to 42% at 5 years.10 With vacancies in the primary care team unfilled, the exodus of staff from general practice is likely to exacerbate workforce shortages and excessive primary care workloads. At the same time, 23.0% of fully qualified GPs excluding trainees are aged 55 years or older,11 so can be expected to retire in the next 5 years given that the average age of retirement for GPs is 59 years.12 The results of our survey echo these findings, and show that rapid intervention is needed to retain and increase the primary care workforce.

Primary Care Networks

Meeting PCN DES Requirements

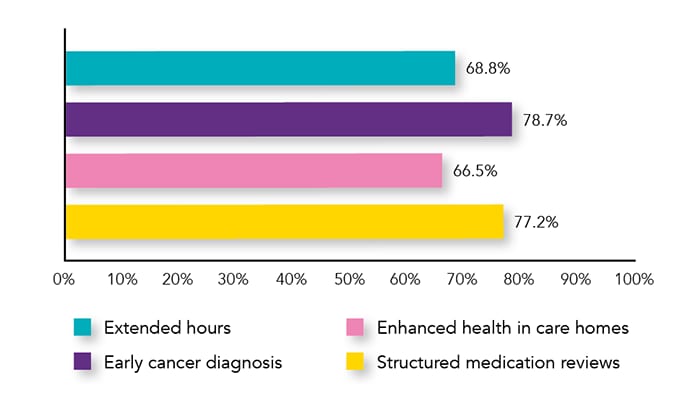

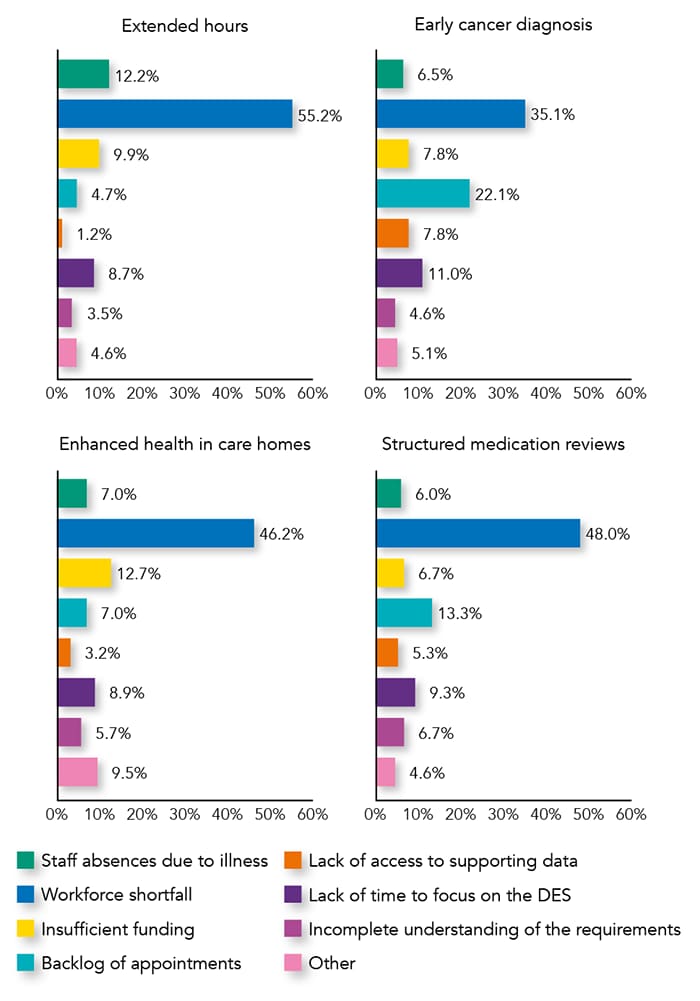

Most participants (79.3%) reported that their practice is part of a PCN, and many expected to be able to meet PCN Directed Enhanced Service (DES) requirements in all four domains: extended hours (68.6%), early cancer diagnosis (78.7%), enhanced health in care homes (66.5%), and structured medication reviews (77.2%; see Figure 3). Consistent with the workforce issues identified earlier in this survey, workforce shortfall was most commonly reported as a perceived barrier to achieving all four requirements (between 35.0% and 55.2%), although 22.1% of respondents also considered a backlog of appointments an obstacle to achieving the requirements for early cancer diagnosis (see Figure 4).

PCN=primary care network; DES=Directed Enhanced Service

PCN=primary care network; DES=Directed Enhanced Service

However, more than half of those surveyed thought that meeting PCN DES requirements is a hindrance to providing other services. In the opinion of more than two-thirds of respondents (67.2%), the introduction of further PCN service specifications—tackling neighbourhood inequalities, personalised care, anticipatory care, and diagnosis of cardiovascular disease—should be delayed. The launch of these four additional service specifications has already been postponed from April 2021 to allow practices to focus on responding to the pandemic, with a new date yet to be announced.5

Are PCNs Working?

The majority of participants felt that the advent of PCNs has not led to a smoother transition for patients between care teams (59.8%), faster patient access to the appropriate healthcare professional (58.2%), improved communication between healthcare professionals dealing with different care needs (53.9%), or care adapted to patients’ specific needs (52.8%). Despite being able to meet PCN DES requirements, there was a degree of frustration about the failure of PCNs to improve these core aspects of patient care—epitomised by this response: ‘I feel there are too many box-ticking exercises, workload [is] becoming far more task-orientated, [and there are] so many new roles appearing that no-one knows who is doing what.’ This was reflected recently at the British Medical Association annual representative meeting, at which delegates passed a motion calling for the withdrawal of GP practices from PCNs by the end of 2023.13

… workforce shortfall was most commonly reported as a perceived barrier to achieving all four [PCN] requirements

Practices may implement a variety of measures if unable to meet PCN DES requirements. In our survey, many suggested that they will prioritise workload (65.4%). Others (33.0%) will begin auditing workload, 28.0% intend to stop taking work from other parts of the health service, and 28.0% said that they hope to divert resources from other services. Some cited more drastic measures, such as closing registration lists to new patients (13.0%), and even resignation from the PCN DES (9.9%).

What Does the Future Look Like for Primary Care?

Challenges Facing Primary Care

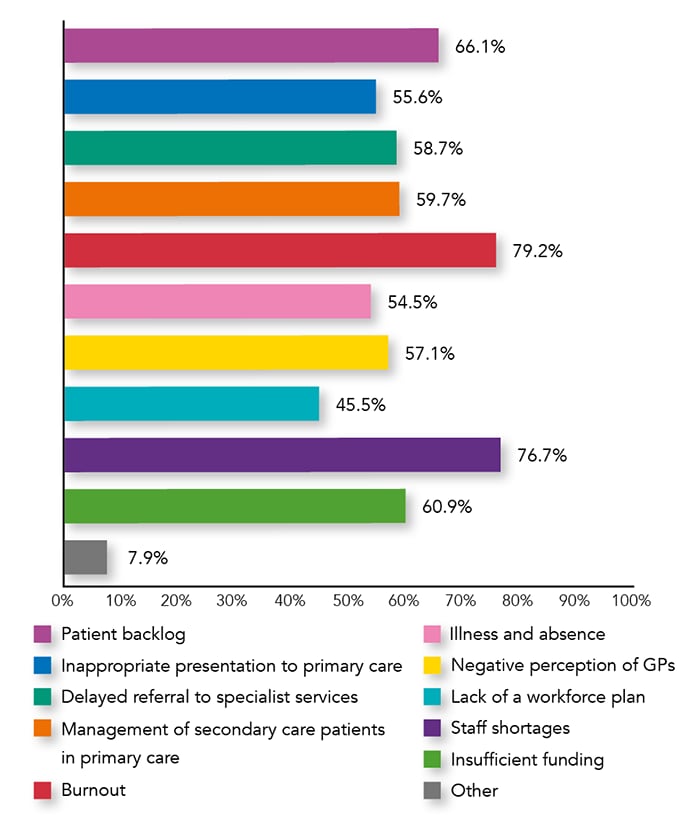

More than 45% of respondents selected all challenges listed in the survey, indicating that many still face considerable obstacles in their working lives (see Figure 5). The most commonly reported challenges facing primary care were burnout (79.2%), staff shortages (76.7%), the patient backlog (66.1%), and insufficient funding (60.9%).

Participants were also invited to identify other challenges, and their responses mirror the findings on overwork and understaffing identified in this survey (see Box 3). Low morale was evident in responses such as ‘overworked, underpaid’; poor communication, fragmented care, media denigration, high patient expectations, and unrealistic Government rhetoric were also recurring themes.

| Box 3: Other Challenges Facing Primary Care Volunteered by Respondents |

|---|

Systemic Issues 'Poor primary and secondary care communication’ ‘COVID-19 only highlighted the dysfunction of the NHS. Nurses’ priority now is better work–life balance, and managers who refuse to accommodate this will keep losing staff’ ‘Nurses’ pay should be increased for the amount of work we do’ ‘The exodus of GPs’ ‘Overworked, underpaid’ ‘Staff morale/poor communication’ External Issues ‘The media’ ‘Unrealistic patient expectations generated by ridiculous rhetoric by Government’ ‘Increased population due to new housing with no new GP facilities’ Combination of Issues ‘Excessive adminand paperwork; science and medicine rapidly evolving—challenge to keep up with knowledge, patient demand outstripping supply, social problems, lack of joined up care and thinking, fragmented services and care’ |

Opportunities for Primary Care

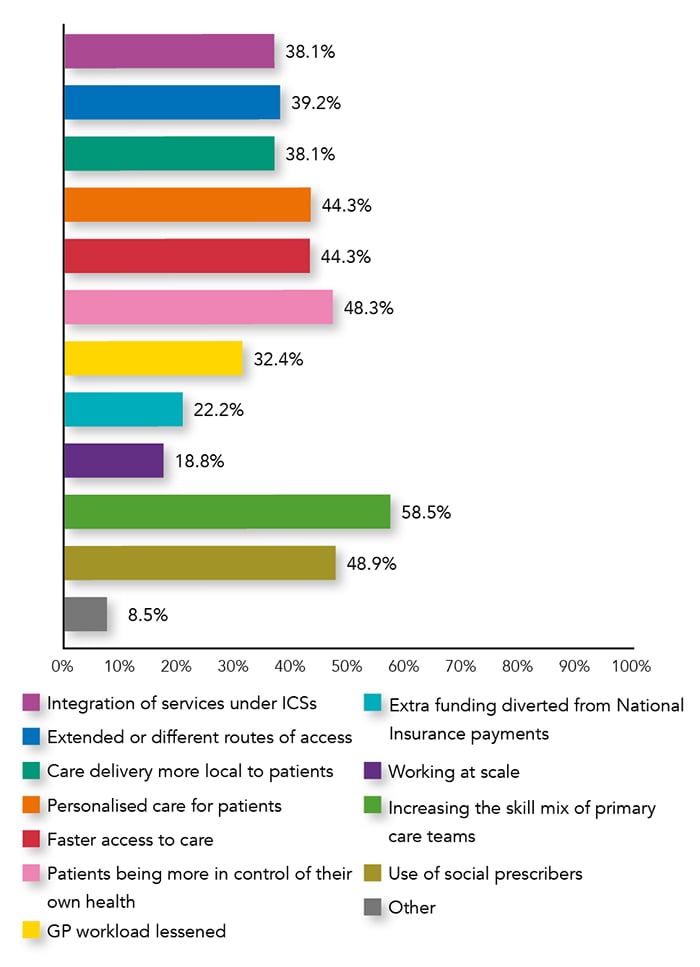

Despite these challenges, many identified opportunities for primary care (see Figure 6). Most commonly reported was the potential to increase the skill mix of primary care teams (58.5%). Others highlighted the use of social prescribers (48.9%), with one respondent observing that it ‘has made a difference in achieving some element of personalised care’. Patient-related opportunities also scored quite highly, including the expectation that patients would exercise greater control of their own health (48.3%), receive more personalised care (44.3%), and experience faster access to care (44.3%).

… more than half of those surveyed thought that meeting PCN DES requirements is a hindrance to providing other services

The opportunities cited by participants reflect some of the key aims of PCNs—to provide integrated services for local populations, and to deliver healthcare that is more personalised, varied, and coordinated across services.3,5 However, the survey responses suggest that there is scepticism about this, with many respondents not considering the options provided to be opportunities. In fact, some felt that genuine opportunities are currently lacking or unachievable (see Box 4), reflected in responses such as ‘I am not sure any of the above represent opportunities [that] will result in improvements’, and ‘I can’t see any opportunities without massive investment in the whole NHS’. Just two participants considered that there were further opportunities outside of those provided in the survey.

| Box 4: Other Opportunities for Primary Care Volunteered by Respondents |

|---|

Opportunities ‘Encourage partnerships’ ‘Patient education’ Other Opinions on Opportunities ‘None of these above options are opportunities. They are proposals, but all rely on having the workforce and capacity to change yet again. There are no realistic opportunities on the horizon’ ‘I don’t know—I’ve resigned from my partnership to go elsewhere as [a] salaried GP before the overload and burnout permanently damages my mental and physical health’ ‘Cannot see that more change is going to help primary care’ ‘We need more trained and skilled staff for all of the above’ ‘Time to have an improved model of care that looks after staff too’ ‘I can’t see any opportunities without massive investment in the whole NHS: a very long-term commitment to it with more, much more money’ ‘Working at scale is damaging for practices and patients—patients get less continuity [and] less care, professional [s] become depersonalised, and morale is low’ |

Summary

The findings of the 2022 Guidelines in Practice readership survey reflect an NHS that is still dealing with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, compounded by staff shortages and financial hardship. Workforce shortages and staff burnout are recurring issues—reflected in the many respondents who felt overworked, had current vacancies in their practices, and intended to change role in future.

This is impacting PCN development: although most said that their practices are able to meet the requirements of the PCN DES, practices are struggling as a result, and more than half of those surveyed thought that further service specifications should be postponed. Enacting PCN service specifications seems to have added to the pressure on an already overburdened primary care workforce, forcing many to make compromises that affect patient care and staff wellbeing.

There appear to be more challenges ahead than there are opportunities for primary care, and the responses reflected a strong cynicism about the future of PCNs. Current initiatives to support primary care within the restructured NHS seem to be inadequate, and measures to reduce the unsustainable pressure on healthcare workers in primary care are falling short. Urgent action is needed to tackle the impact of these issues on both healthcare professionals and patients.

Jemma Lough

Independent Medical Writer

George Burnett

Primary Care Content Editor

Nina Buchan, PhD

Editor, Guidelines in Practice

| Commenting on the Results of the Survey, Dr David Jenner (GP, Cullompton, Devon) said: |

|---|

‘This survey reconfirms the biggest challenge facing primary care teams and PCNs at present: the lack of a sufficient, qualified workforce to undertake the challenges of the PCN DES contract and to cope with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The 5-year GP contract deal apportioned most resources through reimbursement of a tightly defined group of healthcare staff, but brought many new extra work requirements through the PCN DES. There was no published workforce or premises plan to accompany the new service specifications, and PCNs have found it difficult both to recruit and accommodate new ARRS staff. ‘The survey respondents did identify benefits conferred by ARRS staff in terms of increasing the skill mix within primary care teams and improving patient care, but felt that their workload remained excessive. Doctors in particular acknowledged this, likely because they spend more time supervising and training new staff who, when recruited, are not always ready for the roles envisaged for them. In addition, the staff reimbursed are not necessarily those needed to deliver the PCN DES specifications, yet also do not free up enough time to enable GPs to do this. ‘There appears to be significant support for the concepts of PCNs, but frustration with the specific requirements of the DES. A real challenge for PCNs is that practices do not get a large proportion of the additional ARRS funding if they cannot recruit the staff, yet they must still meet all of the requirements of the PCN DES. In my experience, those PCNs that have been able to successfully recruit to most of the ARRS roles feel generally positive, whereas those who cannot feel very differently. ‘Many participants also stated that the PCN DES has brought “tick-box” elements to their workload, alongside top-down micromanagement that is restricting the ability of PCNs to tailor services around the local population. ‘PCNs have had to establish themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many PCN DES and QOF requirements have until this year been suspended or delayed. It is therefore likely that 2022 will pose extra challenges for PCNs and their already depleted workforces—primarily, the provision of new enhanced-access elements of the DES from October 2022 (which were defined but not as yet required at the time of this survey).’ PCN=primary care network; DES=Directed Enhanced Service; ARRS=Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme; QOF=Quality and Outcomes Framework |

A full report of all of the findings from the survey will be published online later in 2022. The winner of a £50 Amazon voucher for participating in our survey is: Shona Daly, Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Lanarkshire Ten readers also won a free subscription to Guidelines in Practice |