Dr Toni Hazell Explains why Seizing the Opportunity to Offer Long-acting Reversible Contraception is More Important Now than Ever

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

As I sit down to write this article, I have an uneasy feeling that this is the calm before the storm. It is mid-September 2020—the first wave of COVID-19 has passed and children are back at school, but new restrictions have just been introduced,1 and there is almost certainly another surge in cases to come and a rocky time ahead. This article discusses contraception in the era of COVID-19, considering how best to provide long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) at the current time, and what to do if there is another wave and face-to-face appointments are restricted even further. It is important that we get this right—terminations of pregnancy have already increased since the start of the pandemic,2 and if access to contraception is poor, then there is the potential for termination rates to rise even higher.

1. Always Offer LARC to Every Patient Seeking Contraception

It is common for a patient to open a consultation by saying ‘I’d like to go on the pill, Doctor’. Sometimes, this phrase does what it says on the tin—the patient has been on the pill before and is happy with it, or they have done their research and decided that the pill is the most suitable method for them. However, ‘going on the pill’ is often used as shorthand for contraception in general; if the patient’s request is taken at face value, the opportunity to discuss LARC methods, which are much more reliable, may be lost. The implant and all intrauterine devices (IUDs) are more than 99% effective with real-life use,3 and the depot injection is around 94% effective.3 Methods that rely on user action every day/week, such as the contraceptive pill and patch, are only 91% effective in real life,3 because people forget to use them. The use of male condoms as a sole method of contraception should generally be discouraged, because their real-life efficacy is only 82%,3 and fertility tracking, otherwise known as natural family planning, has the worst efficacy of all at 76%.3

2. Know How Long LARC Methods can Stay in Place

The amount of time that LARC methods can be left in place varies between the different products, and recommendations about how long they can remain have changed with COVID-19. Not every GP will be a LARC fitter, but every GP can have some basic knowledge of these methods and their duration of action. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) now recommends that the implant and the 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (IUSs) can be used for 1 year past their licensed timescale—further information is given in Box 1.4

Note: For off-licence use of medicines, the prescriber should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for the decision. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information.5

| Box 1: Contraceptive Implants, IUSs, and IUDs—Recommended Duration of Use and Risk of Pregnancy with Extended Use |

|---|

Contraceptive Implants

Hormonal IUSs

Cu-IUDs

IUS=intrauterine system; IUD=intrauterine device; FSRH=Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare; HRT=hormone replacement therapy; Cu-IUD=copper intrauterine device |

It is important to inform patients that the risk of pregnancy is very low when LARC is used in this extended way, but it is not zero, and that generally the numbers of patients enrolled in the relevant studies are too small to calculate exact efficacy rates. Most patients who are concerned about using LARC in this way could be given a progestogen-only pill (POP) to take on top of their LARC method until a change can be arranged. There are very few absolute contraindications for the POP, with the notable exception of current breast cancer, but if uncertain, the 2016 UK medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use should be consulted.12

3. Many Contraceptive Methods can be Prescribed Remotely

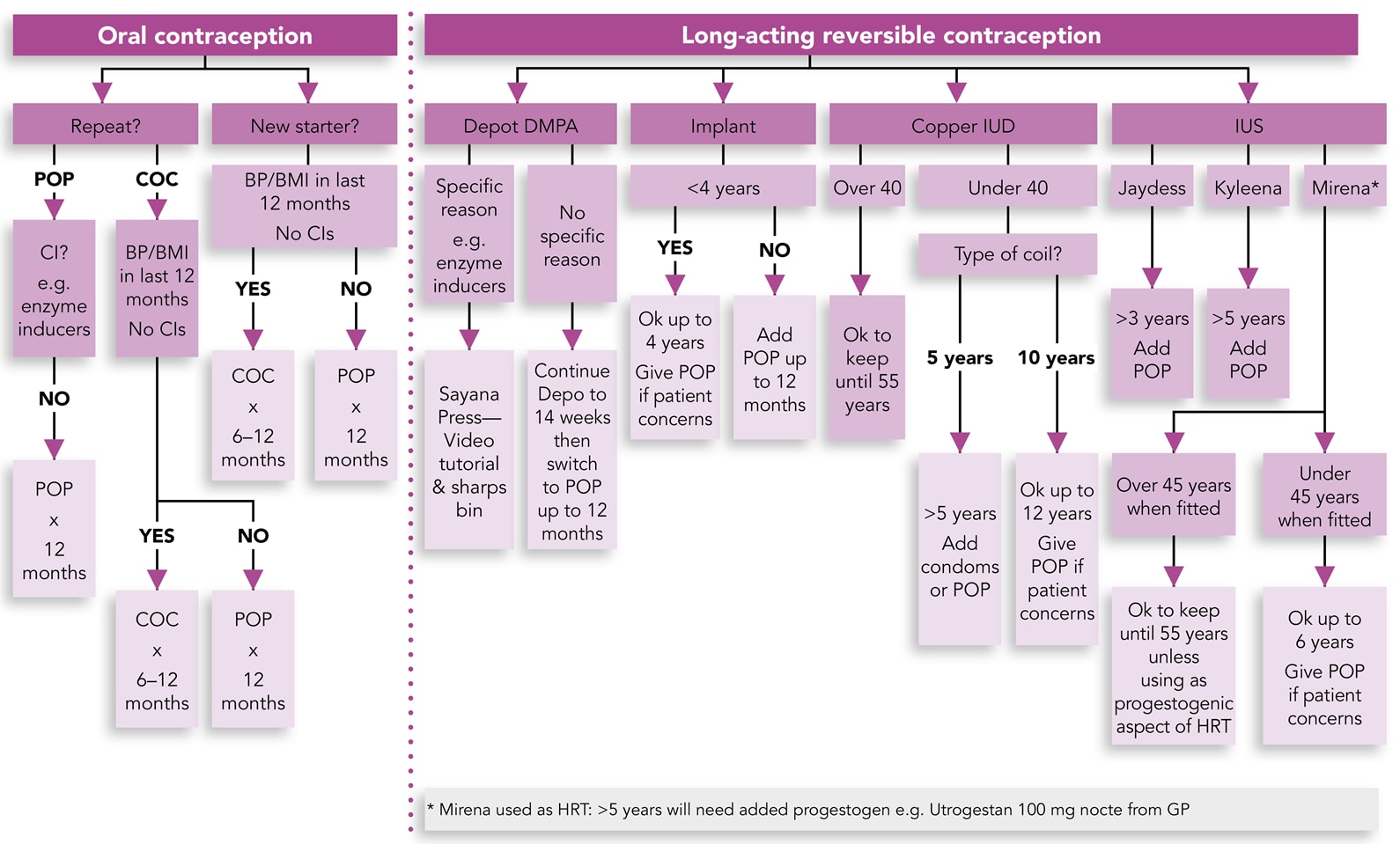

The Primary Care Women’s Health Forum (PCWHF) has produced a useful flowchart to help with the online provision of contraception (see Figure 1).11

Primary Care Women’s Health Forum. PCS C-19 community contraception guide. London: PCWHF, 2020. Available at: pcwhf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/C-19-Community-Contraception-Guide.pdf

Reproduced with permission.

DMPA=depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD=intrauterine device; IUS=intrauterine system; POP=progestogen-only pill; COC=combined oral contraceptive; CI=contraindications; BP=blood pressure; BMI=body mass index; HRT=hormone replacement therapy

Broadly speaking, almost any patient can be prescribed the POP over the phone, unless they have an absolute or strong relative contraindication. Therefore, the POP can be used as a ‘fall-back’ method to provide contraception for people who, for whatever reason, cannot access or use their normal method during COVID-19. It is also fine to prescribe the combined oral contraceptive (COC) over the phone; a history of contraindications can be elicited on the phone and documented in the notes.13 It is necessary to have body mass index and blood pressure measurements taken within the preceding year, but if the patient cannot attend the surgery for this and is unable to perform these measurements at home, then it is safer to prescribe the POP. Written information should be sent to the patient by text or email—good sources of advice include the Family Planning Association14 and University College London’s Contraception choices website.15

4. Consider using Sayana® Press Instead of Depo-Provera®

Anecdotally, the depot injection seems to have become less popular since the implant became available. This is not too surprising, because attending the GP every 12–14 weeks for an intramuscular injection may not be high on a patient’s list of priorities. Sayana® Press (medroxyprogesterone acetate; Pfizer Limited, Tadworth, UK) is the only subcutaneous depot contraceptive injection on the market, and can be safely self-administered at home. The FSRH advises that someone else is present during administration in case of anaphylaxis,16 although this is very rare and it would seem common sense that, after the first few injections, there is unlikely to be such a severe reaction. Sayana® Press should be injected into the abdomen or anterior thigh. The patient can be taught to use it by a healthcare professional (in the same way that patients with diabetes are taught to inject), or they can watch an online video that teaches them how to do it.17 The FSRH-recommended dosing interval is 13 weeks for both intramuscular Depo-Provera® (medroxyprogesterone acetate; Pfizer Limited) and Sayana® Press, but either can be given for up to 14 weeks without the need for additional contraception. Patients who are late with their next injection (up to 16 weeks) can be reassured that the risk of pregnancy is less than 1% and that World Health Organization guidance allows for injection intervals of up to 16 weeks, but UK guidance is more cautious.16 The FSRH gives clear guidance about the provision of a depot injection if more than 14 weeks has passed since the last injection, including considerations of whether unprotected sex has occurred and whether extra contraceptive precautions are needed (see Table 1).16

Table 1: FSRH Advice in Relation to Late Progestogen-only Contraceptive Injections16

| Timing of Injection | Has UPSI Occurred? | Is There a Risk of Pregnancy? | Can EC be Offered? | Can the Injection Be Given? | Is Additional Contraception Required? | Is a Pregnancy Test Required? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Up to 14 weeks since last DMPA injection or Up to 10 weeks since last NET-EN injection | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | No | No |

14 weeks + 1 day or more since last IM or SC DMPA injection or 10 weeks + 1 day or more since last NET-EN injection | No (no sex or used barrier method) | No | N/A | Yes | Yes (7 days after injection) | No |

| Yes, but only in the last 5 days (sex that occurs up to Week 14 or Week 10 is protected) | Yes | Yes. Consider Cu-IUD or LNG EC. The effectiveness of UPA EC could theoretically be reduced by residual circulating progestogen.[A] | Yes* (if bridging method not acceptable).[A] * After LNG EC injection can be given immediately. After UPA EC, delay injection for 5 days.[A] | Yes (until 7 days after injection) | Yes ≥3 weeks since last episode of UPSI | |

| Yes —multiple episodes <5 days ago and >5 days ago | Yes | Yes. The effectiveness of UPA EC could theoretically be reduced by residual circulating progestogen.[A] | Yes* (if bridging method not acceptable).[A] * After LNG EC injection can be given immediately. After UPA EC, delay injection for 5 days.[A] | Yes (until 7 days after injection) | Yes, prior to administering the injection and ≥3 weeks since last episode of UPSI | |

| Yes —multiple episodes >5 days ago and ≤3 weeks ago | Yes | No | Yes (if bridging method not acceptable). | Yes (if bridging method not acceptable). | Yes, prior to administering the injection and ≥3 weeks since last episode of UPSI | |

| Yes —multiple episodes >3 weeks ago | Yes | No | Perform a pregnancy test and if negative administer injectable | Yes (until 7 days after injection) | Yes, prior to administering the injection | |

| [A] See FSRH clinical guideline: emergency contraception (www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/) | ||||||

| FSRH=Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare; UPSI=unprotected sexual intercourse; EC=emergency contraception; DMPA=depot medroxyprogesterone; NET-EN=norethisterone enanthate; N/A=not applicable; IM=intramuscular; SC=subcutaneous; Cu-IUD=copper intrauterine device; LNG=levonorgestrel; UPA=ulipristal acetate | ||||||

| Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Progestogen-only injectable contraception. London: FSRH, 2014 (updated 2020). Available at: www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/cec-ceu-guidance-injectables-dec-2014/ Reproduced with permission. | ||||||

5. Share Information and Bust Common Myths

The internet is a valuable source of advice, but it also allows for easy propagation of myths; it is always useful to remind patients that those who are happy with their contraception form the silent majority who don’t tend to go online and talk about it! Common myths and responses to them are listed in Box 2.

| Box 2: Common Myths About Long-acting Reversible Contraception |

|---|

‘IUDs shouldn’t be used in teenagers or nulliparous people.’ There is no lower age limit, and these devices can easily be fitted in nulliparous individuals or those who have only delivered by caesarean section.18 ‘All patients must have a chlamydia swab before fitting.’ The risk of pelvic infection is highest in the first few weeks after IUD fitting, but the absolute risk remains low. The FSRH advises that a sexual history should be taken, and a screen offered to all patients who are identified as being at risk of a sexually transmitted infection,18 usually consisting of a single swab for gonorrhoea and chlamydia. There is no need to screen for other organisms using a high-vaginal swab. If the patient has no symptoms of pelvic infection, then the IUD can be fitted before the swab results are back as long as the patient can be contacted if necessary with the swab result. ‘IUDs cause ectopic pregnancies/patients with a previous ectopic pregnancy should not have an IUD.’ IUDs drastically reduce the number of pregnancies overall, and they also reduce the number of ectopic pregnancies. If the IUD fails and a pregnancy occurs, then the relative risk of this pregnancy being ectopic is greater than in a patient with no IUD, but the absolute risk of an ectopic pregnancy is still much lower than in a patient using no contraception.18 Past ectopic pregnancy is not a contraindication for the use of an IUD.12 ‘If my periods stop with the implant, I won’t be able to conceive in the future.’ Some anovulatory methods can cause amenorrhoea. Patients can be reassured that this has no impact on their future fertility, and that ovulation returns rapidly when an implant is removed. The only contraceptive method with a known delay in return to fertility is the depot injection, with an average delay of 6–7 months up to a maximum known delay of 1 year, before first ovulation,16 although patients must not rely on this for contraception after the injection is stopped. IUD=intrauterine device; FSRH=Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare |

6. Don’t Be Afraid to Start Fitting LARCs Again

Although there is still a need to reduce footfall in our surgeries, this must be balanced with the risks to patients of being unable to access appropriate contraception. This may be particularly important for those patients in abusive relationships—we know that domestic abuse has increased during the pandemic19 —for whom contraception that their partner doesn’t know about may be particularly important.

It is sensible to take some basic precautions when restarting LARC fittings. Do as much as you can on the phone to reduce face-to-face time—this can include full counselling, and documenting of it, establishing where the patient is in their cycle and answering their questions. You can then text or email a leaflet for the patient to read before they come in. Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (gloves, apron, surgical mask, and visor)20 and make sure that the patient knows in advance to wear a mask. The patient should attend alone unless there is a good reason to have a friend with them (reasons may include the patient being young, having learning difficulties, or needing an interpreter), and it must be confirmed on the day of the appointment that they do not have any symptoms of COVID-19. After the fitting has been done, clean any surfaces that the patient has touched with an antiviral spray before seeing the next patient. A deep clean of the room between patients is impractical. Further information can be found on the websites of the FSRH21 and PCWHF.22 If demand outstrips supply of appointments, consider prioritising those who are vulnerable, for example those who are aged under 18 years, are homeless, are sex workers, have learning difficulties, or are known to be in abusive relationships. You may also want to prioritise those whose LARC methods are the most out of date, and in particular anyone approaching 4 years for an implant or approaching 6 years for a 52-mg IUS.

Remember that most LARC can be quick-started at any time in the cycle if ‘it is reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant or at risk of pregnancy from recent unprotected sexual intercourse’,23 using the FSRH criteria in Box 3. Even if these criteria are not met, the implant, COC, POP, and depot injection can be started as long as the patient understands that there is a risk that they may be in early pregnancy and commits to doing a pregnancy test 3 weeks after the last episode of unprotected sex. More details on quick starting LARC are in the FSRH guidance on the subject.23

| Box 3: FSRH Criteria for Reasonably Excluding Pregnancy23 |

|---|

Healthcare practitioners can be reasonably certain that a patient is not currently pregnant if any one or more of the following criteria are met and there are no symptoms or signs of pregnancy:

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Quick starting contraception. London: FSRH, 2017. Available at: www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/fsrh-clinical-guidance-quick-starting-contraception-april-2017/ Reproduced with permission FSRH=Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare; CG=human chorionic gonadotropin |

Summary

Termination rates increased during lockdown and it is vital that we continue to provide good access to contraception in the likely turbulent months ahead. This article discusses the safe remote provision of contraception, when a long-acting method can be left for longer than its licensed period of use, and how to safely restart fitting long-acting methods of contraception for those who have not yet restarted.

Dr Toni Hazell

Part-time GP, Greater London

Declaration of interest

Dr Hazell is on the executive committee of the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, a role that involves both paid and unpaid work.