Dr Gail Haddock Unpicks Scottish Guidance on the Management of Suspected Bacterial Lower Urinary Tract Infection in Non-pregnant Adult Women

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

In September 2020, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) published a new guideline on the management of suspected bacterial lower urinary tract infection (LUTI) in adult women.1 SIGN 160 replaces SIGN 88, Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults, first published in 2006 and updated in 2012, although it has a narrower remit, focusing on non-pregnant adult women. SIGN 160 also places more emphasis on accurate diagnosis and non-antimicrobial management, in keeping with the prudent antimicrobial prescribing component of the UK’s action plan for reducing antimicrobial resistance (AMR).1,2 This article summarises the recommendations from the SIGN 160 Guideline Development Group (GDG) and learning points for primary care.

The Need for a Guideline

In a population-based survey, over one-third of the adult women who responded reported having had at least one urinary tract infection (UTI) in their lifetime.1,3 Although LUTIs are frequently self-limiting, they can cause significant distress to individuals and have an economic impact as a result of days lost from work. LUTIs are the second most commonly reported indication for an antibiotic prescription in the community (after respiratory infections), accounting for nearly 23% of antibiotic prescriptions.4 These antibiotics are often prescribed empirically to combat the most common uropathogens, which increases the risk of the emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms. The majority of drug-resistant infections are acquired in the community,5 and there is a clear association between prescribing specific antibiotics, such as trimethoprim, for suspected UTI and the development of AMR to those antibiotics.6 For example, surveillance of Escherichia coli (which accounts for the majority of isolates) in Scotland found non-susceptibility to trimethoprim in 33.8% and to nitrofurantoin in 1.8% of isolates; for Klebsiella pneumoniae (which accounts for less than 10% of isolates), non-susceptibility was found to trimethoprim in 23.5% and to nitrofurantoin in 64.4% of isolates.1,7

Diagnosing UTI in Adult Women Aged Under 65 Years

Five urinary symptoms—dysuria, frequency, urgency, visible haematuria, and nocturia—were identified as weak diagnostic indicators of LUTI as diagnosed by laboratory culture.1 Although dysuria was found to be a highly useful single symptom,8,9 it still only exhibited a low likelihood ratio (LR; the effect of a positive test on the change of odds of a disease) of 1.22.8 Haematuria was only found to have a positive predictive value in one meta-analysis.8 In practice, patients tend to have concomitant symptoms, and a single symptom may suggest other diagnoses. Based on this evidence, SIGN 160 recommends that a diagnosis of UTI cannot be confirmed in the presence of a single urinary symptom.1

Multiple symptoms are more predictive of a diagnosis of LUTI, but as UTI symptoms are interdependent, LRs cannot be applied serially. SIGN 160 recommends that a diagnosis of UTI is made in the presence of two or more urinary symptoms (dysuria, frequency, urgency, visible haematuria, or nocturia) and a positive dipstick result for nitrite —this has been highlighted as one of the GDG’s four key recommendations.1

Vaginal discharge is negative predictor of UTI;8,9 other causes of vaginal discharge, such as thrush or urethritis, should be investigated. Suprapubic pain was also a negative predictor in one meta-analysis.8 Therefore, SIGN 160 makes the recommendation: ‘Do not diagnose a UTI in the presence of a combination of new-onset vaginal discharge or irritation and urinary symptoms.’1

Dipstick Testing

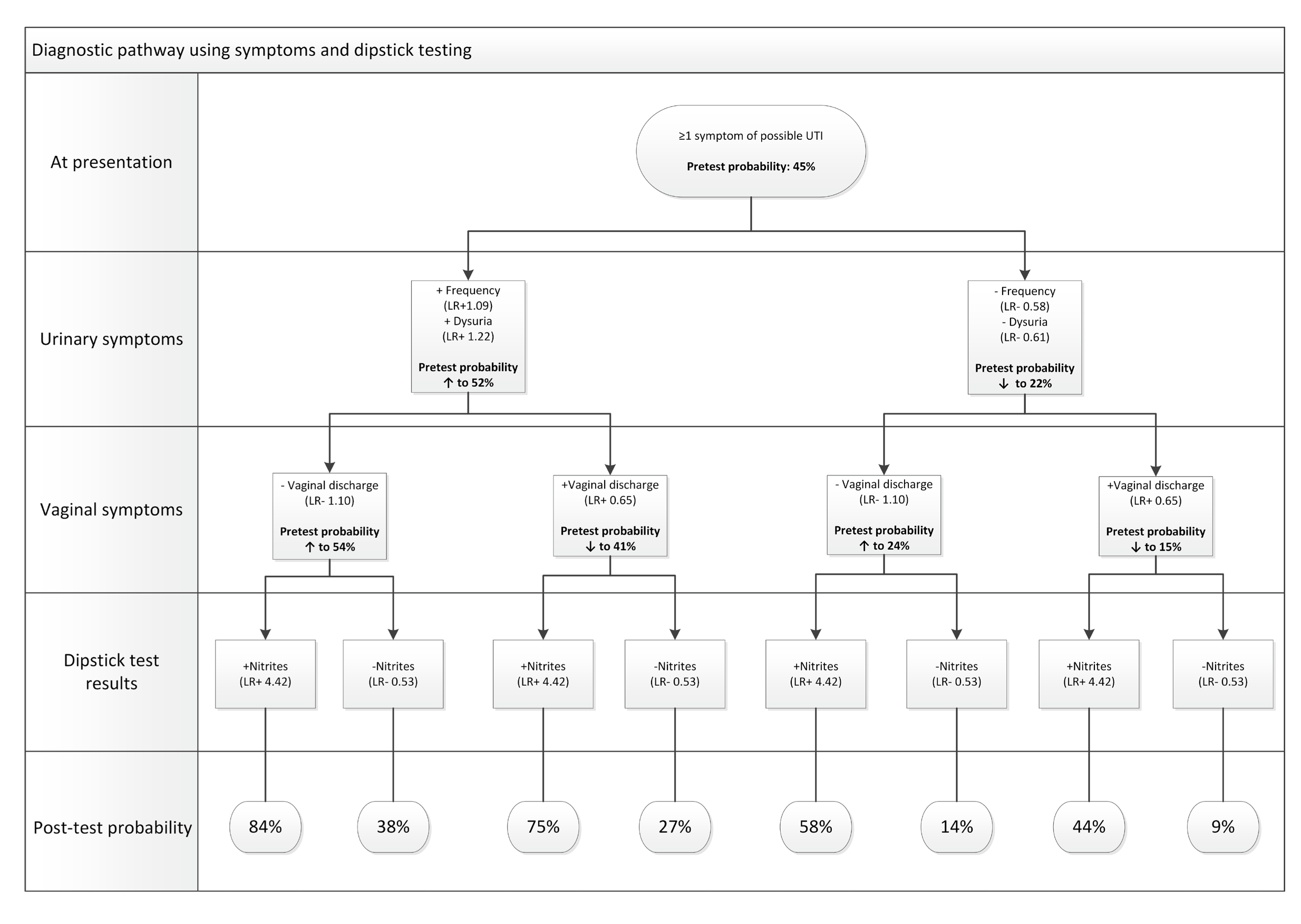

Three meta-analyses showed that dipstick testing significantly increased the accuracy of diagnoses of LUTI.8–10 Table 1 shows the post-test probabilities of infection based on symptoms alone with positive or negative dipstick tests.1,8 Figure 1 provides a decision tree for urinary symptoms and tests in women aged <65 years.1,8

The bacteria E. coli, Klebsiella, and Proteus account for the majority of LUTIs in women aged under 65 years. They reduce urinary nitrates to nitrites, as long as the urine has been in the bladder for more than 4 hours.11 Dipstick tests can detect sodium nitrite at very low levels, acting as a marker for either the presence or absence of the most common bacteria.1 A positive nitrite test significantly helps to rule in a LUTI,8–10 but because bacteria such as Enterococcus and Staphylococcus, although rare, do not convert nitrates, a negative test cannot rule out all pathogens. A positive leucocyte-esterase test gave a moderate increase in post-test probability of LUTI,8–10 but other conditions can cause pyuria. Overall, an economic evaluation showed that dipstick testing in parallel with positive symptoms marginally increased costs, but meant that more women received the correct diagnosis.8,12

Table 1: Post-test Probabilities of Infection Based on sSymptoms Alone and With Positive or Negative Dipstick Tests (at 105 CFU/ml Threshold)1,8

| Symptom (LR+) | Pretest Probability Based on Single Symptom | Post-test Probability of Symptom With a Positive Dipstick Test Result (LR+ 4.42) | Post-test Probability of Symptom With a Negative Dipstick Test Result (LR− 0.53) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysuria (1.22) | 50% | 82% | 35% |

| Frequency (1.09) | 47% | 80% | 32% |

| Urgency (1.17) | 49% | 81% | 34% |

| Vaginal discharge (0.65) | <35%[A] | <70%[A] | <22%[A] |

Note: Pretest probability on presentation (population prevalence) is 44.8%. [A] values reported for threshold of ≥102 CFU/ml, therefore probabilities at higher reference standards are lower. LR=likelihood ratio; CFU=colony-forming units Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of suspected bacterial lower urinary tract infection in adult women. SIGN 160. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2020. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/management-of-suspected-bacterial-lower-urinary-tract-infection-in-adult-women/ Giesen L, Cousins G, Dimitrov B et al. Predicting acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs. BMC Fam Prac 2010; 11: 78. Reproduced under the terms of the CC-BY 2.0 licence. | |||

This sample decision tree displays changes in probability of UTI associated with urinary symptoms (presence or absence of frequency and dysuria), vaginal symptoms (presence or absence of vaginal discharge) and dipstick test result (presence or absence of positive nitrite test). As frequency and urgency have a higher sensitivity than specificity, they are more useful for ruling out UTI when absent than ruling in when present. The reverse is true for positive dipstick results, which strongly increase the probability of infection where present. Likelihood ratios for urinary symptoms are based on a diagnostic threshold of 105 CFU/ml. Likelihood ratio for vaginal symptoms is based on a diagnostic threshold of 102 CFU/ml.UTI=urinary tract infection; LR=likelihood ratio; CFU=colony forming unitsScottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of suspected bacterial lower urinary tract infection in adult women. SIGN 160. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2020. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/management-of-suspected-bacterial-lower-urinary-tract-infection-in-adult-women/

Giesen L, Cousins G, Dimitrov B et al. Predicting acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs. BMC Fam Prac 2010; 11: 78.

Reproduced under the terms of the CC-BY 2.0 licence.

Laboratory Urine Culture

Sending urine specimens to the laboratory for microscopy will give a more accurate diagnosis than dipstick testing alone, but is much less cost-effective and can cause delays.1,12 The GDG’s pragmatic advice is to send urine samples to the lab when:1

- there is a history of antibiotic-resistant urinary isolates

- the patient has taken any antibiotic in the preceding 6 months

- the symptoms fail to respond to empirical antibiotics

- there are two or more urinary symptoms and a negative nitrite dipstick test result (to avoid false-negative dipstick test results, when the urine may not have been held in the bladder for the 4 hours or the pathogen is one of the 5% that cannot convert nitrates).

Management of LUTI in Women Aged Under 65 Years

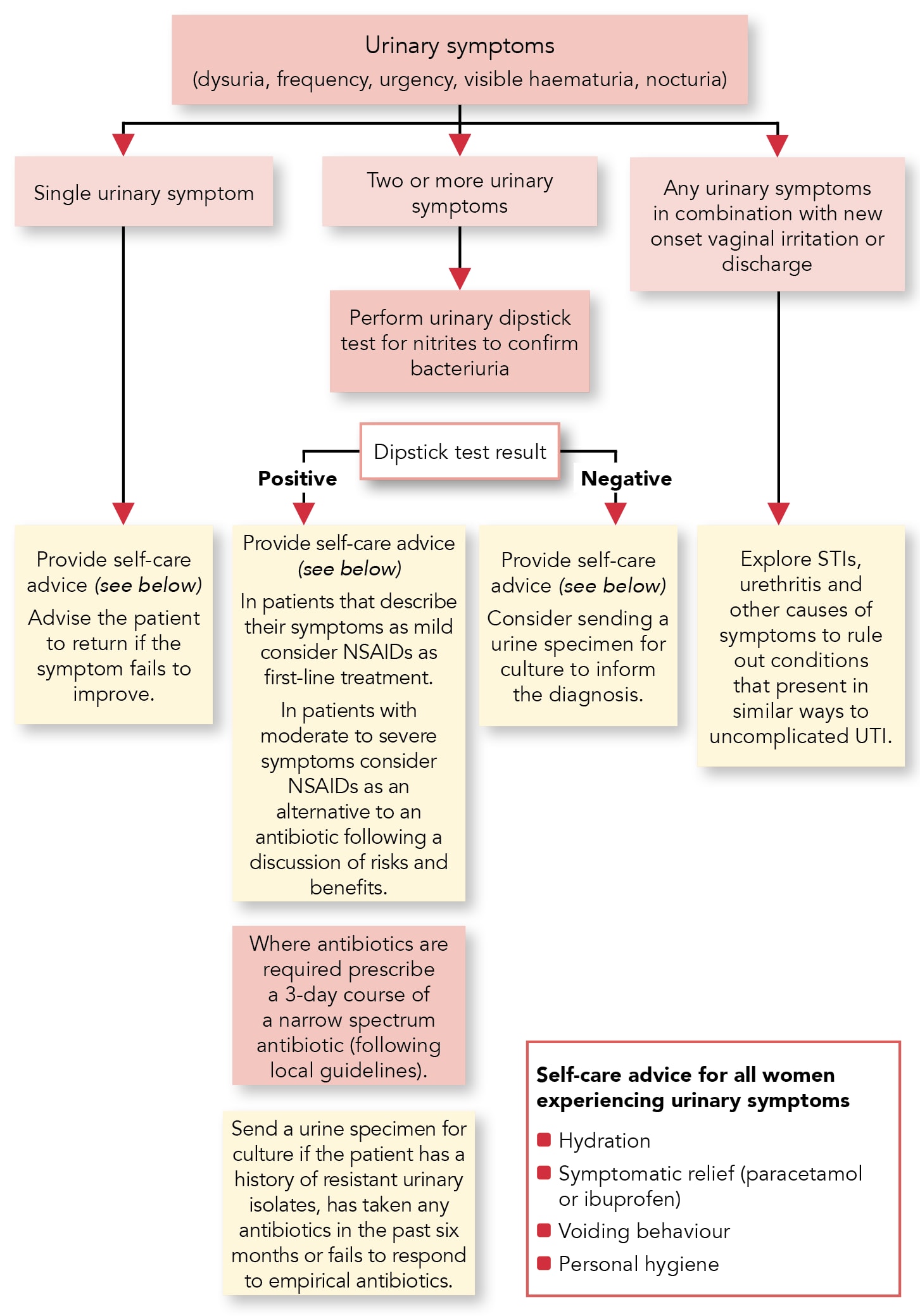

Figure 2 shows an algorithm for diagnostic and management options in non-pregnant women aged <65 years presenting with a suspected LUTI.

LUTI=lower urinary tract infection; NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; STI=sexually transmitted infection; UTI=urinary tract infectionScottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of suspected bacterial lower urinary tract infection in adult women. SIGN 160. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2020. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/management-of-suspected-bacterial-lower-urinary-tract-infection-in-adult-women/

Reproduced with permission

Decisions on managing LUTI should take into account the symptom burden and impact. Explaining the natural history of LUTI will help with shared decision making. For example, if left untreated:13

- increased daytime frequency lasts on average 6.3 days

- dysuria lasts on average 5.25 days

- urgency lasts on average 4.71 days

- feeling generally unwell lasts on average 5.33 days.

No specific evidence was found to support the commonly given advice of increasing fluid intake, but the GDG considered it a low-cost intervention without evidence of harm that could theoretically improve clearance and reduce symptoms by dilution of bacteria and growth nutrients.1 Urinary alkalisers are still recommended in some formularies in other countries for symptomatic relief, but their safety and efficacy are unknown;14 in addition, they may theoretically interfere with the effectiveness of nitrofurantoin by increasing urine pH.15

SIGN 160 recommends that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered as first-line treatment in women aged <65 years with suspected uncomplicated LUTI who describe their symptoms as mild. The rationale for the use of NSAIDs is to minimise self-limiting symptoms. In three studies cited in the guideline, the use of an NSAID was associated with a significant reduction in total antibiotic use.16–18 Symptom resolution occurred within 4–6 days in patients receiving an NSAID compared with 2–5 days in those receiving antibiotics. There was a small increased risk of pyelonephritis in the NSAID group, but the GDG considered that this risk could be mitigated by discussion of the risks and benefits of treatment with an NSAID with the patient (including the normal cautions for NSAID use), restricting NSAID use to 3 days, and a strong statement on contacting their prescriber if their symptoms persist or worsen.1

If antimicrobials are indicated for treatment of LUTI, SIGN 160 recommends the use of short (3-day) courses, as this is clinically effective and minimises the risk of adverse events. The choice of agent should take into account the risks and benefits in the individual and local antimicrobial guidance. See Table 2 for a comparison of selected antimicrobial agents.

A Cochrane review comparing treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) with antimicrobials or placebo reported an increased risk of adverse events associated with antimicrobial treatment.24 ASB rates vary depending on the study, but tend to increase with age, frailty, and co-morbidity.1,24 SIGN 160 recommends that treatment is not offered for ASB in non-pregnant women of any age.

Table 2: Comparison of Selected Antimicrobial Agents for Treatment of LUTI1

| First-line/Empirical Agents | Comments |

|---|---|

| Nitrofurantoin | First-line treatment option. Narrow-spectrum agent with low rate of resistance. Not suitable for patients with eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73 m2. Efficacy reduced when taken concurrently with over-the-counter urinary alkalinising remedies containing citrate. |

| Trimethoprim | First-line treatment option. Narrow-spectrum agent. Dose adjustments required in patients with renal impairment. Resistance rate for E. coli 33.6% in Scotland.7 |

| Alternative agents | Comments |

| Amoxicillin | Second-line treatment option but high rate of resistance in E. coli (52.8% in 2018)7 so only suitable for targeted treatment. |

| Pivmecillinam | Second-line treatment option which is useful for targeted treatment (against organisms sensitive to pivmecillinam). Narrow-spectrum agent. |

| Fosfomycin | Second-line treatment option which is useful for targeted treatment (against organisms sensitive to fosfomycin). Broad-spectrum agent. Single-dose treatment. |

| Restricted agents | Comments |

| Cefalexin | Broad-spectrum agent. 0.5–6.5% of penicillin-sensitive patients will also be allergic to the cephalosporins. If a cephalosporin is essential in patients with a history of immediate hypersensitivity to penicillin, because a suitable alternative antibacterial is not available, then cefixime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, or cefuroxime can be used with caution; cefaclor, cefadroxil, cefalexin, cefradine, and ceftaroline fosamil should be avoided.19 Cephalosporins are associated with an increased risk of CDI.20,21 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Use only where other antibiotic choices are unsuitable. Adverse safety profile—MHRA warning; do not use for LUTI unless all other agents unsuitable.22 Fluoroquinolones are associated with an increased risk of CDI.20,21 |

| Co-amoxiclav | Restricted treatment option. Less effective in achieving cure than other classes. Broad-spectrum agent. Contraindicated in patients with history of co-amoxiclav-associated jaundice or hepatic dysfunction and those with history of penicillin-associated jaundice or hepatic dysfunction.19 Resistance rates for E. coli around 25% in Scotland.23 Co-amoxiclav is associated with an increased risk of CDI.20,21 |

Local formularies will determine the dose and duration of individual antimicrobials used for treatment of UTI. LUTI=lower urinary tract infection; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; E. coli =Escherichia coli; CDI=Clostridioides difficile infection; MHRA=Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of suspected bacterial lower urinary tract infection in adult women. SIGN 160. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2020. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/management-of-suspected-bacterial-lower-urinary-tract-infection-in-adult-women/ Reproduced with permission | |

Diagnosis and Management of Suspected UTI in Women Aged Over 65 Years

Although the age of 65 years has been used as a cut-off for research, women aged over 65 years comprise a diverse population that includes fit and healthy women as well as frail and elderly women with co-morbidities. Most of the evidence found by a large meta-analysis of diagnostic indicators that led to the recommendations in SIGN 160 applied to women aged over 65 years in long-term care.25 Healthcare professionals will need to use their clinical judgement in this age group and tailor care to the individual.

It is important to be aware that women aged 65 years and over, especially those in long-term care facilities, may not display the usual symptoms and signs of UTI that are seen in younger women.1 Functional deterioration and/or changes to performance of activities of daily living may be indicators of infection in frail older people.1 A holistic assessment is needed in frail elderly people to rule out other causes of both urinary symptoms and functional decline; for example, urinary retention, metabolic abnormality, constipation, dehydration, pain, and polypharmacy.1

SIGN 160 recommends that dipsticks are not used for the diagnosis of UTI in women aged 65 years and above in long-term care facilities or in frail elderly people requiring assisted living services. Nitrites are only a marker for the presence of certain bacteria; testing for nitrites is unhelpful in this group, in which the incidence of ASB can reach 70%.1 Also, the causal urinary pathogens tend to be atypical in older patients, including those that may not convert nitrates.26 Urine specimens should only be sent for culture to confirm the pathogen and antibiotic sensitivity in women aged 65 years and above prior to starting antibiotics for a UTI.

There was no evidence for the use of NSAIDs in women aged over 65 years. In the absence of studies to guide choice of antimicrobial agent in this age group, the SIGN 160 recommendation was extrapolated from the under 65 years age group, with more emphasis placed on individual patient factors, such as impaired renal function, polypharmacy, and an increased risk of adverse effects, including incidence of Clostridioides difficile infection.1 One randomised controlled trial (RCT) suggested that 3-day courses were as effective as 7-day courses in controlling most symptoms in this age group, with fewer adverse effects.27

Management of Recurrent UTI

Recurrent UTI is defined as at least three UTIs per year, or two UTIs in the past 6 months. Recommendations include that women with a history of recurrent UTI should increase their fluid intake to around 2.5 litres per day.1,28 The evidence for the benefits of cranberry products and probiotics was conflicting, so no recommendation was made.1 One Cochrane review suggested that vaginal (not oral) oestrogens reduced the proportion of postmenopausal women with UTIs,29 but the differing application methods used in the studies analysed meant that their results could not be pooled, so the GDG made no recommendations about their use.1

Prophylactic antimicrobials should only be considered after discussion of self-care approaches and the risks and benefits of the antimicrobial treatment involved, particularly in the over 65 years age group. To minimise the development of resistance, antimicrobial prophylaxis should be used as a fixed course of 3–6 months, then reviewed.1,30 This should allow time for the bladder to heal.

Catheter-associated Lower Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary catheterisation provides easier access for uropathogens to the bladder and interferes with host defences. The most important risk factor for infection is the duration of catheterisation,1,31 which supports the necessity of regular review of the need for a catheter. Health Protection Scotland uses a National Catheter Passport to provide education for patients and families, and to facilitate communication between healthcare teams.32

The presence of cloudy or odorous urine or pyuria are not indicators of catheter-associated lower urinary tract infection (CA-UTI) and dipsticks should not be used in this group.1,33 Clinical signs and symptoms, including fever, rigors, altered mental state, acute haematuria, pelvic discomfort, or costovertebral angle tenderness, should be used to diagnose CA-UTI and, if present, urine culture should be employed to confirm the diagnosis and causal pathogen. If antibiotics are required, broader-spectrum treatment is usually needed in line with local antimicrobial guidelines. There is insufficient evidence to support a recommendation either in favour of or against the replacement of catheters before prescribing antimicrobials, but the guideline acknowledges that this is current practice and that there are theoretical reasons for doing so.1

In patients with an indwelling urinary catheter, antibiotics do not generally eradicate ASB. A smaller group of patients use intermittent self-catheterisation, and the recommendation here is that antibiotics should not be used to prevent UTI without full discussion of risks and benefits to the individual—although prophylactic antibiotics may reduce the incidence of UTI by approximately half, the consequences are increased costs and increased development of AMR.1,34

Practical Implications with Implementing the Recommendations

The two most significant new recommendations provided in SIGN 160 are:1

- in women aged under 65 years, diagnose a UTI in the presence of two or more urinary symptoms (dysuria, frequency, urgency, visible haematuria or nocturia) and a positive dipstick result for nitrite

- consider NSAIDs as first-line treatment in women aged <65 years with suspected uncomplicated lower UTI who describe their symptoms as mild.

The increased use of dipsticks in most symptomatic patients will have practical ramifications,especially given the increasing number of patients seeking UTI treatment from community pharmacists who can provide a supply antibiotics, if appropriate, under Patient Group Directions, which has implications for training, toilet facilities, and testing facilities. The risks and benefits of bringing patients to healthcare facilities for dipstick testing during the coronavirus pandemic (rather than evaluating them via remote consultation based on history alone) will also have to be assessed.

The feasibility of the need for urine to have been in the bladder for 4 hours (not always easy if a woman has significant urinary frequency) is not widely understood and this is important for an accurate nitrite result. SIGN is developing a patient version of the guideline, which will provide information for women on how best to provide a urine sample that can be used in testing for a UTI. It will also include patient information on when to use NSAIDs for symptomatic relief.

Summary

Lower urinary tract infection in women is common, often unpleasant, but usually self-limiting. One of SIGN 160’s main aims is to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing for LUTI. This can be achieved by patient education, accurate diagnosis, symptomatic management where appropriate, and—if antibiotics are necessary—the shortest course possible from local formulary guidance.

Dr Gail Haddock

GP, Highland

Vice Chair, Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group

Member of the Guideline Development Group for SIGN 160

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; UTI=urinary tract infection |