Dr Kash Bhatti Provides 10 Top Tips for GPs Who Want to Get Started With Dermoscopy and Diagnose Benign Skin Lesions With Confidence

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

Defined as the non-invasive examination of the skin using skin-surface microscopy, dermoscopy is becoming part of the lexicon of general practice. This year, the Royal College of General Practitioners launched a Dermatology toolkit, which champions dermoscopy.1 In an effort to improve the quality of referrals and reduce demand on secondary care, CCGs are investing in dermatoscopes for primary care to upskill GPs and for teledermatology.

This article explains how dermoscopy can help GPs, how to get started, and how to navigate the learning curve, become confident, and reduce skin-lesion anxiety.

NB The term ‘dermoscopy’ is interchangeable with ‘dermatoscopy’; this article uses ‘dermoscopy’ as this term is used more regularly worldwide.

1. What is a Dermatoscope?

A dermatoscope is a tool that facilitates the assessment of skin. Like an ophthalmoscope or an otoscope, a dermatoscope illuminates and magnifies. The difference between a magnifying lens with a light and a dermatoscope is that a dermatoscope reveals subsurface details, whereas examination using the naked eye or a magnifying lens only shows what is on the skin’s surface, via reflected light. A dermatoscope eliminates surface reflections to reveal details from the epidermis and upper layers of the dermis. Because skin lesions have characteristic structures and appearances, visualising these structures helps to build a picture of what a lesion is. Thus, recognising the structures that are present can reveal the diagnosis.

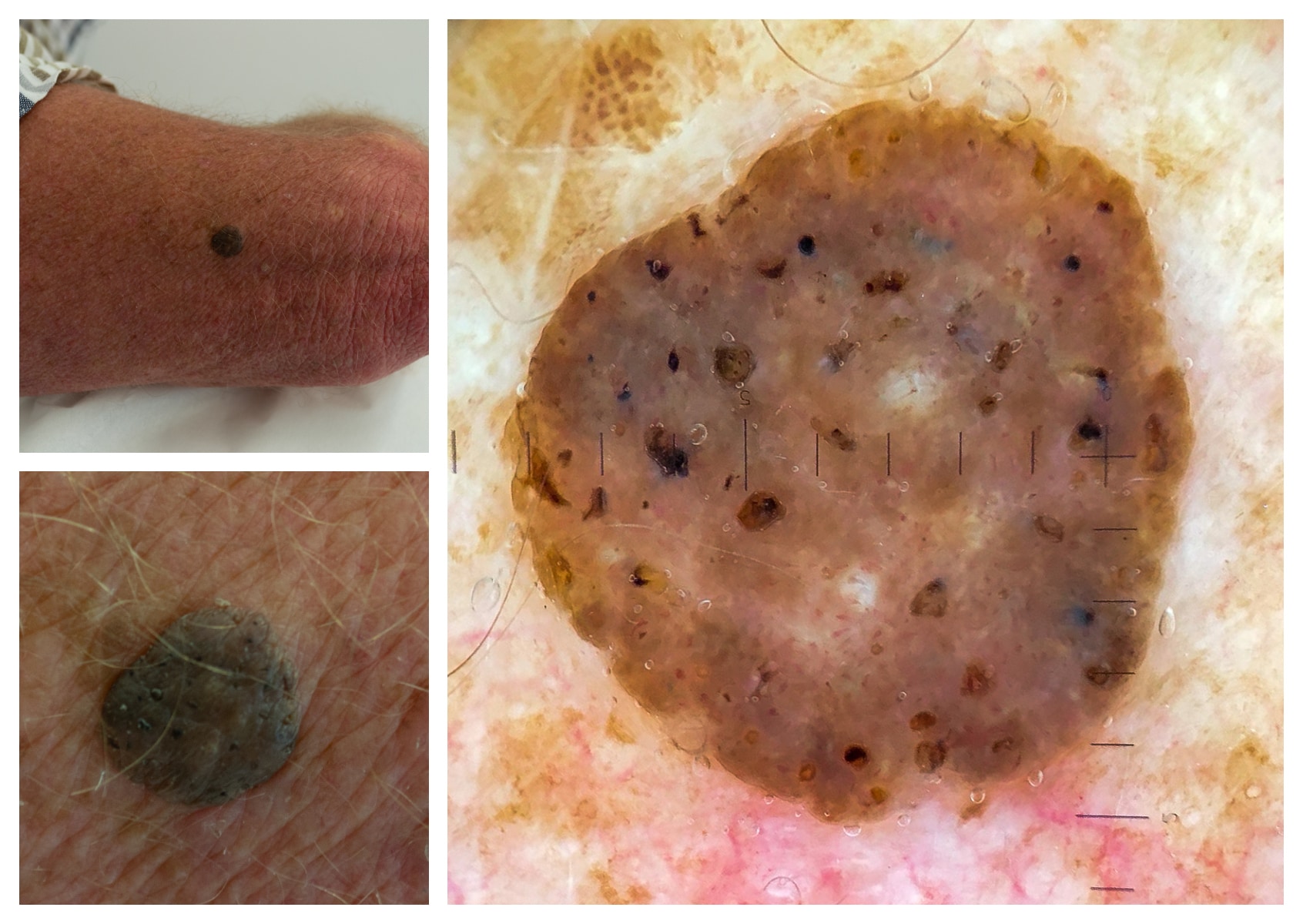

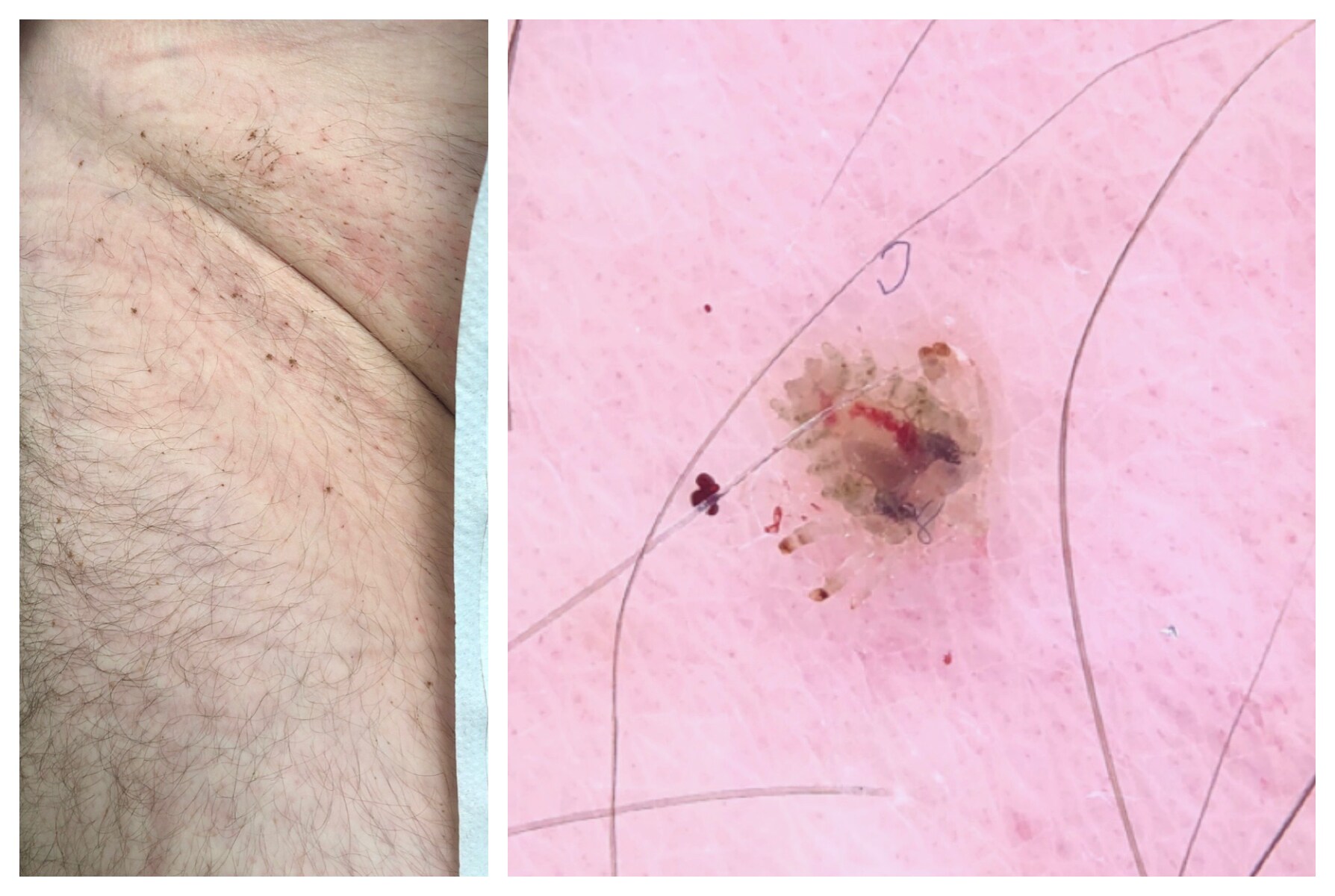

Figure 1 shows a lesion simply magnified and then visualised dermoscopically. Dermoscopy reveals characteristic structures to allow a confident assessment.

A solitary lesion was brought to our attention because of its dark colour (top left, lesion on arm; bottom left, zoomed-in). The history suggested a lesion present for several months at least, without change, and not causing symptoms. This lesion had a warty feel and a ‘stuck-on’ appearance. On dermoscopy (right), a sharp border was visible, the colour was a structureless greyish-brown, and there were numerous scattered, grainy brown and orange clods (also known as pseudocysts). There were similar lesions on the patient’s back, but smaller and not as dark. Putting all the clues together allowed a confident diagnosis of seborrhoeic keratosis.© Bhatti K, 2019.

2. How Will Dermoscopy Help Me?

The majority of skin lesions are benign. On average, a GP will diagnose one basal cell carcinoma a year, one squamous cell carcinoma every 1–2 years, and one melanoma every 3–5 years.2 Compare these frequencies with the vast number of lesions seen that will be benign. Hence, the role of dermoscopy in primary care is to assist with the confident diagnosis of benign lesions. Any patient with a lesion that cannot be diagnosed as clearly benign, or that raises suspicions of cancer, must be referred or treated as appropriate.

Often, a patient will present with a changing lesion, a brand-new lesion, or a lesion that they had never noticed before. A lesion may be symptomatic, such as being itchy or crusty. Many patients are anxious. Rightly, patients seek medical advice for anything new, changing, or concerning. Dermoscopy helps to make our evaluation that much more thorough, and that much more reassuring, when we are diagnosing a benign lesion.

3. What Should I Buy and What Else May I Need?

Most dermatoscopes magnify skin 10 times: this is the standard level of magnification that should be used. Older dermatoscopes require a fluid such as alcohol or ultrasound gel between the skin and the dermatoscope. This leads to time-consuming examinations if a patient has multiple lesions scattered around the body, because fluid or gel must be applied to each lesion before the lesion can be checked.

Newer dermatoscopes allow non-contact dermoscopy by employing polarising lenses that negate the need for a contact fluid. This is called polarised dermoscopy. Older dermatoscopes that require contact fluid have simpler lens arrangements and are termed non-polarised. Some devices are hybrid devices that allow polarised non-contact dermoscopy, which is valuable to rapidly scan the skin, while also allowing use of a contact fluid to permit non-polarised dermoscopy. The differences between non-polarised and polarised dermoscopy are few; some structures (such as white lines, which can be an important indicator of malignancy) are only highlighted by polarised dermoscopy, whereas other structures (such as the bright, shiny, white dots of seborrhoeic keratoses) can only be seen using non-polarised dermoscopy. Neither type of dermatoscope is an absolute must-have; either type will help GPs to confidently diagnose benign skin lesions.

Dermatoscopes vary in quality, build, and features, and hence in cost. There are several manufacturers and suppliers of dermatoscopes.3 Prices generally start from the hundreds. For the beginner, it is not necessary to spend a lot; simple, effective tools can be purchased for less to start off with. An illuminated loupe magnifier (10 times magnification), using alcohol gel as contact fluid, is a good starting point for non-polarised dermoscopy.4

Ask about obtaining a dermatoscope from your CCG. There may be a push to do so, or a local enhanced service, or a campaign to get GPs using dermatoscopes in your area. If you have to buy a dermatoscope, contact manufacturers and try out different dermatoscopes over a period of time. Explore what suits you and your budget.

In addition to a dermatoscope, think about a camera. Record what you see, firstly for patients’ notes, but also for your own learning. Numerous manufacturers have adaptors for their devices. Again, there is a range of equipment to suit every budget. Often, I use a patient’s smartphone, so that they have a copy of the picture and can bring it with them to a review appointment or if seen in hospital. However, it is important to be aware of patient confidentiality and safe use of images.1,5

4. I Have Got the Dermatoscope; How Do I Get Started?

Dermoscopy is a new skill that requires a degree of understanding and time to practise and master. Seeing lesions for the first time will be an illuminating experience, revealing structures not previously encountered before and different to any past dermatology teaching. The excitement comes in understanding that benign lesions have several repeatable and characteristic structures and features which, over time, become easily recognisable, permitting rapid diagnosis. Given that the majority of lesions encountered will be benign, there is an abundant pool of patients to see and learn from.

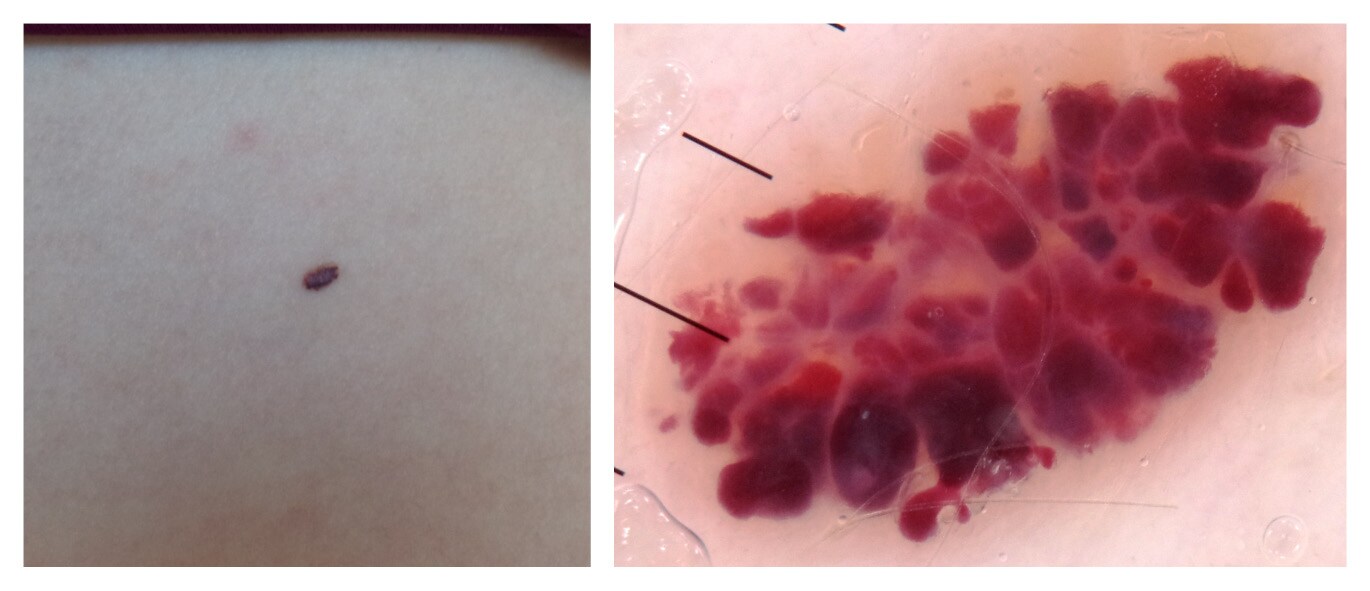

The ideal lesions to start with are seborrhoeic keratoses (Figure 1) and angiomas (Figure 2). Most patients from middle age upwards will have several cherry angiomas or seborrhoeic keratoses. The history will be of long-standing, static lesions. If a GP sees 10 patients a week and examines their backs, with multiple similar lesions per patient, it is possible to rapidly form a database of images of just these two diagnoses. Seborrhoeic keratoses are the most common benign lesions referred to skin cancer clinics. Recognising more seborrhoeic keratoses alone will improve the quality of referrals. From there, and armed with more knowledge, it is possible to move on to dermatofibromas and naevi. Over time, a GP can build a knowledge base of patterns and structures, start to confidently separate the definitely benign from the uncertain and the definitely-not-benign, and manage accordingly.

This is an example of an angioma. Angiomas are thought to be ubiquitous from the age of 50 onwards. This isolated lesion down the dermatoscope (right) demonstrates red globules in varying shades, well demarcated from each other. Dermoscopy allows a confident diagnosis and the patient can be reassured that this is a benign lesion. © Dr Stephen Hayes, 2019

Reproduced by kind permission

Dermoscopy brings a new language that can seem daunting. Initially, dermoscopic structures were named metaphorically.6 The disadvantage is that a metaphoric term makes sense to the beholder, but not necessarily to others. Subsequently, a unified language was created, based upon descriptive geometric terminology, to describe all dermoscopic features.7 This universal language means that descriptions can be understood and recognised by anyone, so reducing confusion.

5. What Should I Know About Skin Lesions?

Dermoscopy is only a tool to aid in skin lesion recognition: it is still necessary to know the basics about skin lesions. The overall diagnosis and decision should be reached using clues in the history, general examination, skin lesion assessment, and dermoscopy. For example, moles, or melanocytic naevi, change over time. They emerge, grow, stabilise, then over time involute and disappear. We tend not to develop new naevi after the age of 45, with rare exceptions. So a new, bland-looking naevus in a 65-year-old should be concerning, however benign it looks, because biologically it is unexpected. Long-standing lesions on the trunk that do not change over time and look and feel warty, like seborrhoeic keratoses, are likely to be benign, especially if there are several that are dermoscopically similar. But a new nodule—solitary, growing, firm, possibly with bleeding—should be referred urgently, regardless of what dermoscopy suggests, because this may be any kind of tumour. Always take a new, changing, growing, or bleeding lesion seriously. It is necessary to be sure of benign features in the history, as well as in the examination, to arrive at a benign diagnosis.

6. How Do I Assess a Skin Lesion?

A skin lesion assessment begins with addressing the patient’s concerns and expectations, investigating the history of the lesion, and assessing risk factors.

Clues in the history that are important regardless of lesion type include the age of the patient, lesion history, any recent change, and symptoms such as bleeding or non-healing. Other clues in the history relate to the background risk of the patient: the skin type of the patient (how likely they are to tan or burn: the risk of skin cancer is highest in those most likely to burn easily), and any previous personal or family history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, or excessive sun exposure, any of which should raise suspicion. It is important to find out what concerns the patient has. These can provide further insight and also guide the consultation.

A general examination is next. The skin should be assessed to look at any other lesions and assess the lesion in the wider context of the other lesions present. A standout lesion (‘ugly duckling’) is more likely to be concerning and warrants careful assessment. Look for signs of sun damage that may suggest a high-risk patient.

The lesion of concern is assessed next. Is the lesion on a sun-exposed site (e.g. face) or high-risk site (e.g. genitals)? The site, size, feel, and macroscopic features should be documented, followed by dermoscopic evaluation and documentation. Assess the lesion in the context of other lesions, both macroscopically and dermoscopically. A concerning naevus will be much more reassuring if there are several other naevi that look similar; look for biological similarity, not architectural or mirror-image lesions. Similar lesions may vary in size or shape, but overall their dermoscopic colours and structures should be alike.

7. How Do I Make Sense of What I See?

Dermoscopy opens a world of colours and structures, which organise into patterns. One way to learn dermoscopy is to learn the various geometries and recognise lesions, over time, by pattern recognition. The other way, which is more powerful, is to understand how colours and structures form and assemble to reveal the diagnosis. This is called pattern analysis. Evidence suggests that beginners perform equally well whichever method they choose.8

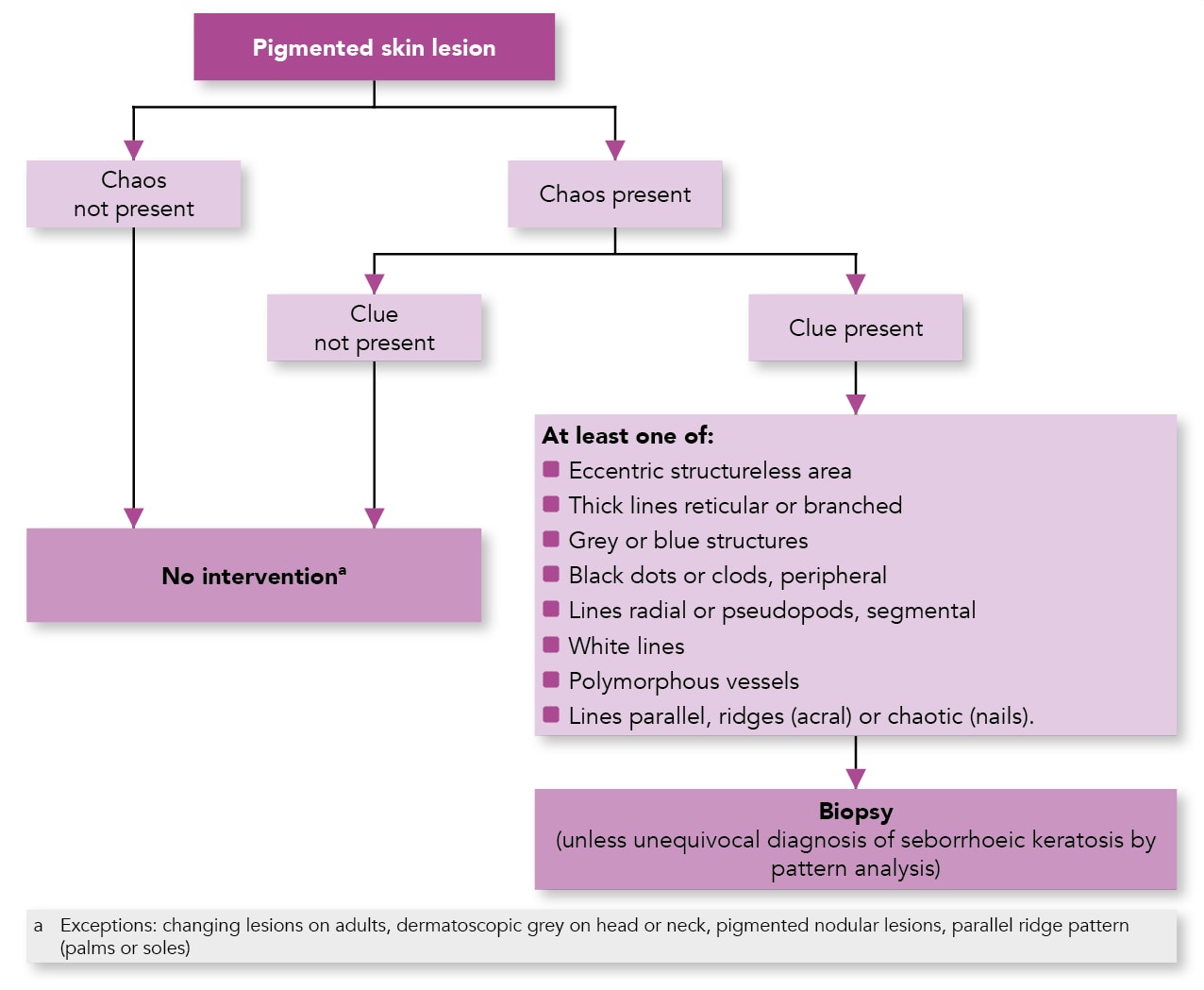

To start making sense of what you see, numerous algorithms exist for triaging lesions.9 Two general, all-purpose algorithms for beginners are Chaos and clues10 (Figure 3) for pigmented lesions and Prediction without pigment11 (Figure 4) for non-pigmented lesions. These will help triage the majority of lesions, but there are important exceptions to note. No single algorithm is foolproof enough to diagnose all lesions. Over time, you will develop your own algorithm; essentially, you will advance to using pattern analysis and pattern recognition interchangeably to assess and triage all lesions.

Adapted with permission from The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners from: Rosendahl C, Cameron A, McColl I, Wilkinson D. Dermatoscopy in routine practice - ‘Chaos and clues’. Aust Fam Physician 2012; 41 (7): 482–487. Available at: www.racgp.org.au/afp/2012/july/dermatoscopy-in-routine-practice/

.png)

Adapted from Rosendahl C, Cameron A, Tschandl P et al. Prediction without pigment: a decision algorithm for non-pigmented skin malignancy. Dermatol Pract Concept 2014; 4 (1): 9.© 2014 Rosendahl C et al. Reproduced under the terms of the CC-BY 4.0 licence.

8. How Can I Avoid Missing a Cancer?

It is to normal to feel nervous about a new method of assessing skin lesions given the high stakes. The good news is that the majority of skin lesions are benign; remember, assess lesions in the context of other lesions. A solitary lesion is concerning, but a lesion present for several years, without dramatic change and similar to other lesions, is likely to be benign. There are of course exceptions—a lentigo maligna on the face can be slow growing, often to the point of escaping detection, and appear bland.

Over time, the more that you see and recognise benign features, the more that lesions with questionable features will start to stand out. When suspicious of cancer, refer. Short-term photography can be used for flat lesions that you suspect are very likely to be benign. An example may be a lesion either present for several years or newly noticed, but that macroscopically and dermoscopically looks benign, in a young patient. Short-term photography can be employed and reviewed for any change in 3 months’ time. In this case, robust methods are needed to ensure that the patient will re-attend. If this is not guaranteed, then refer. Monitoring should never be used for raised or nodular lesions, because these lesions are already growing; similarly, do not use monitoring just to put off a decision to refer until a later date or in the hope that, in 3 months’ time, you will be able to assess the lesion better and give a diagnosis.

9. What Else Can Dermoscopy be Used For?

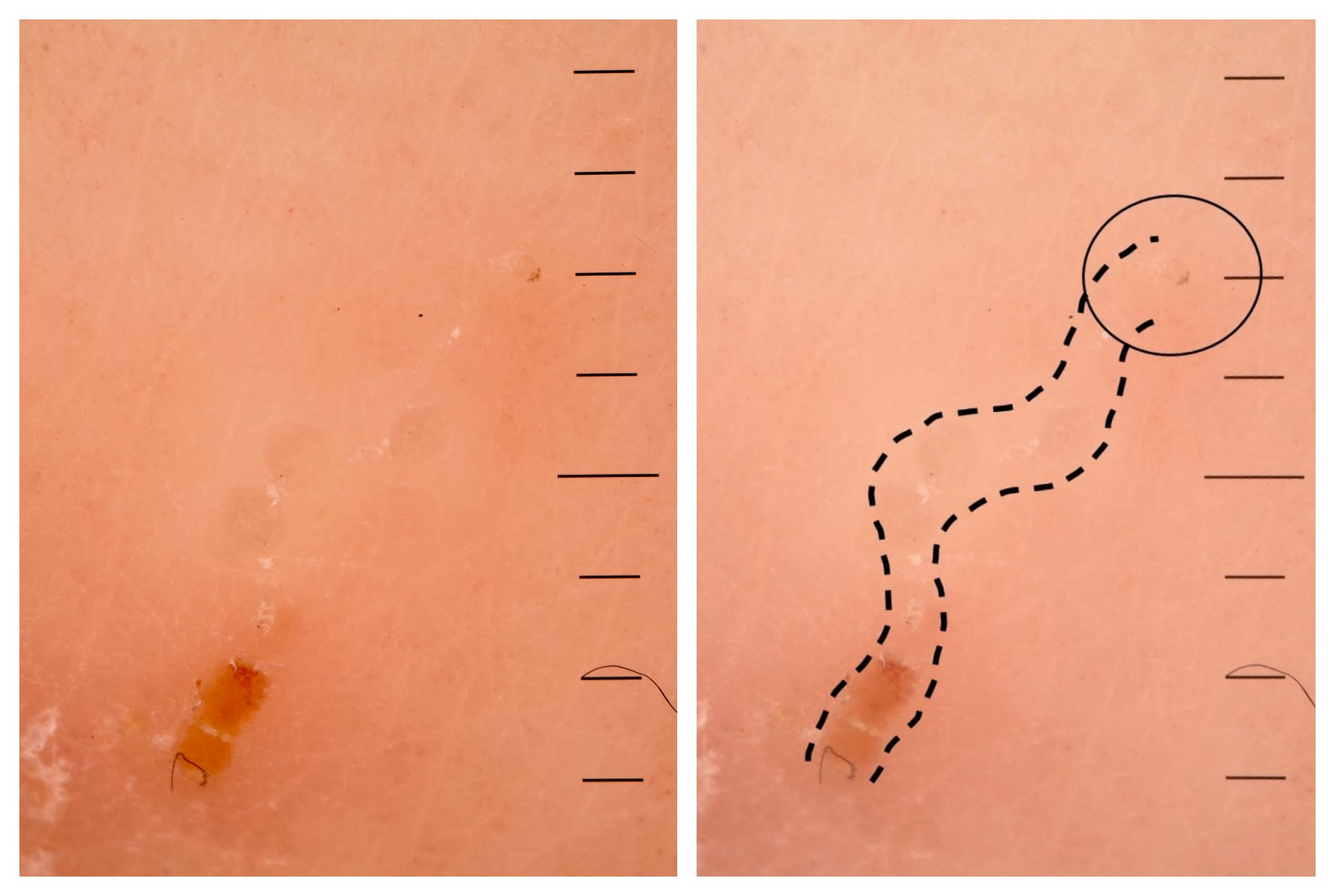

Research into dermoscopy is increasing exponentially. Dermoscopy can be used for general dermatology and helps in the diagnosis of inflammatory conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, and lichen planus. It can be used to assess pityriasiform conditions such as rosea, guttate psoriasis, and lichenoides. It is also used to assess hair conditions such as alopecia areata, hair loss, and scarring alopecia. In addition, dermoscopy can be used to monitor treatments such as in psoriasis or alopecia areata, and in several conditions it can replace a biopsy. Once you start using dermoscopy to see scabies (Figure 5), you can never ‘un-see’ it, and diagnosis becomes easier over time. Similarly, other infections and infestations can be diagnosed using dermoscopy (Figure 6). Finally, dermoscopy can also be used for nail disorders and can identify superficial foreign bodies in the skin.

These are dermoscopic images of a single burrow on the foot of a child taken after several months of uncontrollable itching and presumed eczema (left). The burrow shows a weaving track, which commenced with an orange serous crust, featured a whitish scale (‘contrails’ metaphorically) on the route, and culminated in a triangular shape (‘delta wing’ metaphorically), which is the head of the scabies mite. The panel on the right clarifies the structures seen. Instant diagnosis was possible with no need for biopsy.© Bhatti K, 2019.

A middle-aged patient presented with a short history of itchy skin. He remarked that he saw black spots on his skin wherever he was itchy (left). The black dots were scattered over his body. Dermoscopy revealed the diagnosis: body lice (right). The dermoscopic picture captures a louse staying still for the picture owing to it feeding.© Bhatti K, 2019.

10. Where Can I Learn More?

There is a vast array of information available to get started and excel in dermoscopy.1 The International Dermoscopy Society (IDS) offers free membership, videos suiting all levels hosted on YouTube, and e-learning modules.12 Dermoscopedia is an encyclopaedic resource from the IDS authored by leading dermoscopists.13 Numerous blogs are present online that go through cases.1 In addition, the Primary Care Dermatology Society runs several courses for beginner, intermediate, and advanced dermoscopists and allows face-to-face interaction with experienced tutors.14 Likewise, the University of Cardiff hosts a 12-week online learning course for dermoscopy.15 Ask local GPs with a specialist interest in dermatology if it is possible to attend clinics and look at lesions together, or attend suspected skin cancer clinics in hospital.

Dr Kash Bhatti

GP and GP trainer, GPwSI Dermatology; Leeds, UK

Executive committee member, Primary Care Dermatology Society