Ruari O’Connell and Gupinder Syan Discuss Treatments for Eczema and the Role of the Practice Pharmacist in Managing Patients with Eczema in Primary Care

| Read this Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

This article has been developed in association with Soar Beyond Ltd.

|

Eczema (and/or atopic dermatitis) can be defined as a group of diseases that result in inflammation of the skin. These diseases are characterised by itchiness, red skin, and a rash. Eczema can present at any age and is particularly common in children. An estimated 15 million people in the UK could have eczema, which shows the large caseload that could potentially be well managed in primary care.1 In 2015, GPs wrote around 27 million prescriptions for topical agents used in the treatment of eczema, which equates to a significant prescribing workload at the individual practice level.1

Different types of eczema can co-exist and the main types include irritant, atopic, allergic contact, venous, and discoid. Atopic eczema is the most common type and comprises dry skin as well as infection and lichenification. Lichenification is thick, leathery patches of the skin caused by scratching and rubbing of the affected areas and may complicate chronic eczema.2 The area of skin involved can vary from small to the entire body. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, whereas in long-term cases the skin may become thickened.2

Inflammation can be caused by exposure to a specific allergen or long-term exposure to environmental or occupational factors. Taking a detailed history from the patient can help to identify triggers; however, it is not always possible to identify the allergen or indeed remove exposure to it.

The Role of the Pharmacist

In general practice, chronic disease consultations and medication reviews are increasingly being conducted by clinical pharmacists. Many pharmacists working in general practice come from community pharmacy backgrounds, and will therefore already have experience in supporting patients to manage their eczema. Pharmacists working in general practice typically lead on areas with clinical indicators in the quality and outcomes framework (QOF), and delivery of local prescribing incentive schemes. Although there is no clinical indicator in the QOF for eczema, pharmacists can help with the significant practice workload associated with eczema, while ensuring patients achieve their desired treatment and management outcomes.

Please note: Patients with severe refractory eczema should be referred as it is best managed under specialist supervision. This may require treatment with phototherapy or stronger medications that act on the immune system.2

Eczema Treatment

The primary aim of eczema treatment is to reduce the exposure of the skin to trigger factors by:

- identifying and avoiding trigger factors if possible

- hydrating the skin to provide an effective barrier to prevent the entry of trigger factors.

Emollients are the mainstay treatment of eczema. Topical corticosteroids are also sometimes required, particularly during a flare-up when eczema symptoms worsen.

Emollients

Dryness of the skin and the irritant eczema that ensues require regular and liberal application of emollients at least twice a day to the affected area, which can also be supplemented with bath or shower emollients. Emollients are the mainstay of treatment and should continue to be used alongside other treatments or even if the eczema improves.2

Emollients are typically under-prescribed and under-used.3 The National Eczema society recommends an adult should use at least 500 g of emollient per week (at least 250 g for a child).4 In practice this may not be feasible, so the patient should have had a discussion about what to use and when, and what size the prescribed product should be to reduce waste, e.g. a small tube size to keep in the handbag for work may be appropriate.

The choice of emollient may be a matter of trial and error. The most expensive product is the one that is not used, so it is important to find an emollient that works for the individual patient. Almost every treatment has the potential to cause a skin reaction in a patient with sensitive, inflamed skin. If an emollient causes inflamed skin to sting on initial application, advise the patient to try it for a few days to see if the eczema improves and the stinging stops. If the patient is sensitive to one emollient, try another to see if there is any reaction. It may be necessary for the patient to use more than one emollient, on different parts of their body, depending on what works best for their condition. It may be appropriate to prescribe a small quantity when trialling a new emollient to avoid waste in case it does not work or suit the patient.

Pharmacists should know which emollients are on their local formularies, consider the quality and cost-effectiveness of the products available, and select the product that works best for the individual patient.

It is important to remind patients that emollients can contain a large amount of paraffin; this often soaks into clothing and bedding, which can become a fire hazard. Clothing and bedding should be washed regularly.4

Topical Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are used to relieve symptoms by suppressing the inflammatory reaction when other measures, such as emollient use alone, are ineffective. Topical corticosteroids are not curative and may cause rebound exacerbations of the condition upon discontinuation; it is important to counsel patients appropriately to manage their expectations. The potency of topical corticosteroids should be appropriate to the severity and site of the condition, and treatment should be reviewed regularly. Patients who experience regular flares (two to three per month) can apply a topical steroid on two consecutive days each week to prevent further flares.2

The potency of topical corticosteroid, the area of the body it is applied to, and the duration of treatment will affect the systemic side-effect profile. Rare side-effects include adrenal suppression and even Cushing’s syndrome. All patients using topical corticosteroids must be closely monitored and reviewed at regular intervals in practice. Particular care is required in the use of potent and very potent topical corticosteroids. Mild and moderate potency corticosteroids are associated with fewer side-effects.5

As with any consultation, it is important to manage the patient’s expectations. The potency of topical corticosteroids (except mild) is determined by the severity and extent that they blanch the skin.6 In real terms, this means that the red itchy skin the patient is complaining about will quickly become less red and less itchy on application of a topical corticosteroid, and the stronger the steroid the more quickly this will happen. However, this is not a long-term solution as it can increase the risks of steroid-related side-effects, so it is better and safer to hydrate the skin using emollients.

The potency of topical corticosteroid also affects the area of the body it can be safely used on, for example, mild corticosteroids are usually used on the face and on flexures, and potent corticosteroids are generally used on the scalp, limbs and trunk, or for discoid or lichenified eczema in adults.2 Very potent preparations should not be used in children without specialist dermatological advice.7

The formulations of topical therapies are also an important consideration; for example, water-miscible corticosteroid creams are more suitable for moist or weeping lesions whereas ointments are generally chosen for dry, scaly, or lichenified lesions, or where a more occlusive effect is required. When minimal application to a large or hairy area is required, or for the treatment of exudative lesions, then a lotion may be more useful or appropriate.2

For a list of topical corticosteroid preparations by potency, see the NICE BNF treatment summary on topical corticosteroids.5

Using the finger-tip unit (FTU) to describe the amount required for treating different areas may help patients to understand appropriate quantities to ensure they do not overuse topical corticosteroids:3

- one adult FTU is the amount of ointment or cream expressed from a tube with a standard 5 mm diameter nozzle, applied from the distal crease to the tip of the index finger

- one FTU is equivalent to about 500 mg and is sufficient to treat a skin area about twice that of the flat of the hand with the fingers together.

Table 13 details the quantity of topical corticosteroid in FTUs to apply for one application, and Table 25 details suitable quantities of corticosteroid preparations to be prescribed for specific areas of the body.

Table 1: Quantity of Topical Corticosteroid to Apply For One Application3

| Body area | Number of Finger-tip Unitsa for Aadults and Children | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | ||||||

| 6–10 years | 3–5 years | 1–2 years | 3–12 months | ||||

| Face and neck | 2.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| Arm and hand | 4 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| Leg and foot | 8 | 4.5 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| Trunk (front) | 7 | 3.5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Trunk (back) including buttocks | 7 | 5 | 3.5 | 3 | 1.5 | ||

| a One adult finger-tip unit (FTU) is the amount of ointment or cream expressed from a tube with a standard 5 mm diameter nozzle, applied from the distal crease to the tip of the index finger | |||||||

| © NICE 2018. Eczema—atopic. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/eczema-atopic All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this publication. | |||||||

Table 2: Suitable Quantities of Corticosteroid Preparations to be Prescribed for Specific Areas of the Body—Adults5

| Area of the Body | Creams and Ointmentsa (g) |

|---|---|

| Face and neck | 15 to 30 |

| Both hands | 15 to 30 |

| Scalp | 15 to 30 |

| Both arms | 30 to 60 |

| Both legs | 100 |

| Trunk | 100 |

| Groins and genitalia | 15 to 30 |

| a These amounts are usually suitable for an adult for a single daily application for 2 weeks | |

| © NICE British National Formulary. Treatment summary—topical corticosteroids. bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/topical-corticosteroids.html All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this publication. | |

Developing the Relevant Competencies

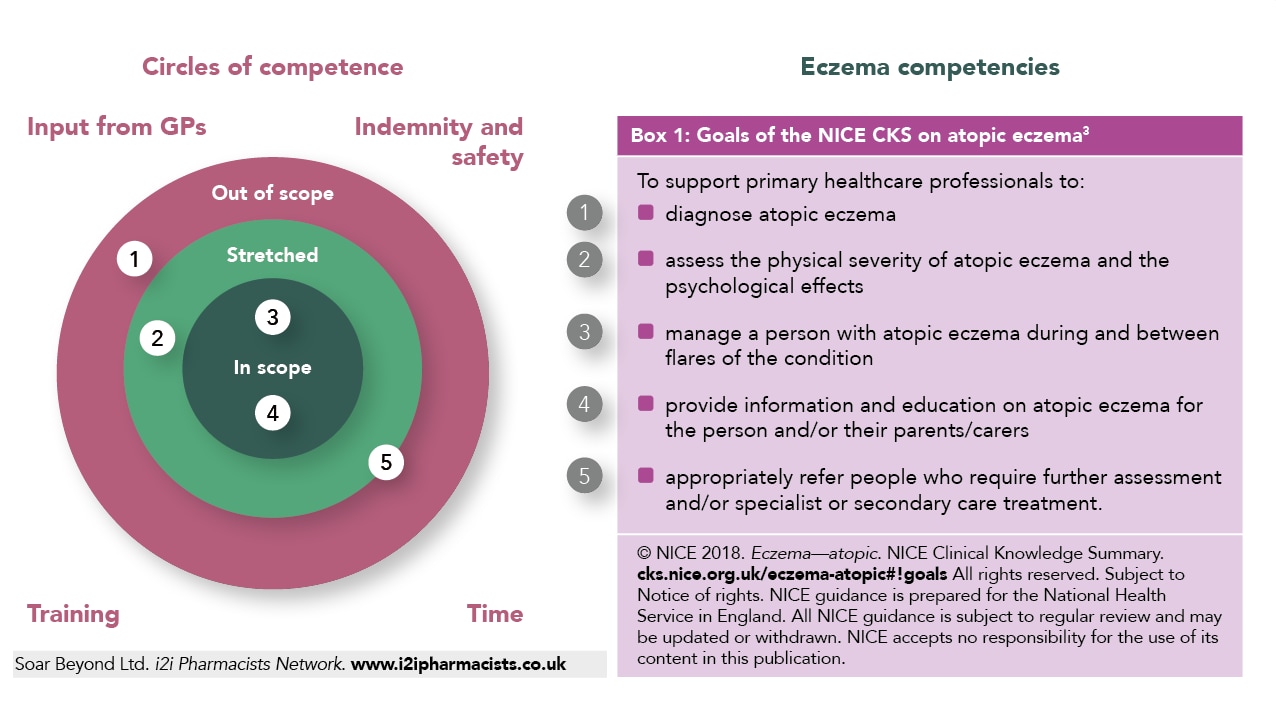

When deciding whether it is appropriate for the clinical pharmacist to take on the management of eczema for the practice, it is important to understand the goals for primary care healthcare professionals (HCPs) in caring for patients with atopic eczema, and how they align with the pharmacist’s existing skillset.

The NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary (CKS) on atopic eczema3 states the goals for managing atopic eczema (see Box 1). The i2i circle of competence tool (Figure 1)8 describes how the goals for managing atopic eczema can be mapped to the pharmacist’s competencies. The pharmacist defines whether each goal is

- within their scope of practice—something they can do now, and do well and safely

- in ‘stretch’ scope—something that can be achieved with some further training, support from GPs, or indemnity where required. This can usually be reached within 2–4 months, depending on the nature of the work and risk involved

- outside of their scope of practice—something they cannot do without considerably more training, support, and evaluation, for example, diagnosis.

After assessing the goals and competencies, a development plan is agreed between the pharmacist and supervising GP, detailing any necessary support and training requirements for the pharmacist to competently and effectively manage patients with eczema in the practice. The case study in Box 2 describes the practical steps to setting up a pharmacist-led eczema clinic in general practice. With more exposure and experience, clinical pharmacists working in general practice can become skilled to specialise and even diagnose long-term conditions such as eczema within their scope of practice.

By working with the clinical pharmacist to map current competencies and by supporting a development plan, GPs can quickly reduce their workload associated with eczema, while ensuring patients achieve their desired treatment and management outcomes. Eczema is an ideal area for involvement of clinical practice pharmacists as it is often linked to prescribing incentive schemes and can therefore provide both clinical and financial gains for the practice.

| Box 2: Practical Steps to Setting up a Pharmacist-led Eczema Clinic in General Practice—Sase Study | |

|---|---|

Situation: A clinical pharmacist, who has recently made the transition from a community pharmacy setting into general practice, has taken on an emollient prescribing audit, which includes carrying out switches from certain emollients to more cost-effective alternatives, as part of a local CCG incentive scheme. Task: In addition to leading on the scheme and improving on cost-effective prescribing of emollients, the clinical pharmacist proposes that they are well-placed to support a review of patients, which will:

Action:

Table 3: Audit Performance Metrics | |

| Proposed Audit Outcome | Metric |

| Improved patient clinical outcomes in eczema management |

|

Help with GP workload |

|

| Reduction in medicines wastage by appropriate counselling and prescribing of steroids and emollient use |

|

| Support the practice to achieve the income from the incentive scheme |

|

| CCG=clinical commissioning group; CKS=clinical knowledge summary; SNOMED CT=Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms | |

Ruari O’Connell

Senior Clinical Pharmacist

Gupinder Syan

Senior GP Pharmacist; Clinical Outcomes and Training Manager for i2i Network by Soar Beyond Ltd.

To find out more about how Soar Beyond and the i2i Network can help your practice achieve better management of long-term conditions through supporting clinical pharmacists working in general practice, please get in touch by emailing: i2i@soarbeyond.co.uk