Dr Jenny Bennison Summarises the SIGN Guideline on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Highlights the Role of Primary Care in Identifying Children who are At Risk

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) published SIGN 156, Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol1 in January 2019. SIGN 156 is the first UK guideline on prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE); it covers a spectrum of conditions that can have a huge impact on neuropsychological development but frequently go unrecognised. It is therefore essential for GPs across the UK to be alert to the possibility of PAE in patients of all ages; recognition and identification of specific problems can lead to targeted help and better outcomes for those affected.

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) was first described in 1973 as a pattern of physical defects, growth deficiency, developmental delay, and cardiac anomalies caused by PAE.2 Traditionally, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) has been used as a collective term to describe a range of conditions with different patterns of effects caused by exposure to alcohol during pregnancy. Other than fetal alcohol syndrome, none of these conditions have specific diagnostic criteria or are coded in the International classification of disease (ICD) or Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM).3,4 The use of FASD as a single umbrella term to describe a range of different conditions is one of the reasons behind healthcare professional confusion, artificially low diagnostic rates, and poor epidemiological data.

SIGN 156 recommends that FASD should be used as a diagnostic term.1 This means that individuals who might previously have been coded as FAS, partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopment disorder (ARND), alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD), or fetal alcohol effects (FAE) will now only be coded as FASD (with two subdivisions). By reporting clear and specific diagnostic criteria and by no longer using FASD as an umbrella term, SIGN hopes that this new approach will help:

- healthcare professionals to be more confident in assessing and diagnosing the condition using simplified terminology

- the collection of prevalence data by ensuring that all children who receive a diagnosis can be recorded under a consistent term.

Neurodevelopmental disorder related to PAE is one of the most common preventable causes of neurodevelopmental impairment; the UK prevalence of FASD is estimated to be around 3.2%.1 It is likely that FASD is under-diagnosed because awareness among professionals (including GPs, specialists, and teachers) and the general public is low. It is possible that many children go through education with an inaccurate diagnosis, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism spectrum disorder. Crucially, inappropriate treatments and support, and a lack of targeted interventions, could deprive children with FASD of important opportunities to fulfil their potential.

Primary care professionals have a critical role to play because they are in an ideal position to gather accurate information about maternal alcohol history before, during, and after pregnancy. This assessment is key to the diagnostic process, as is routine recording and sharing of accurate information.

The Need for a Guideline

In the UK, and Scotland in particular, alcohol consumption in women of childbearing age is common and is recognised as a significant public health issue.1,5,6 Although surveys suggest an overall reduction in self‑reported alcohol intake among women in Scotland, the majority of women still drink some alcohol, and many continue to drink during pregnancy.1 Some of those who do drink at this stage in their lives may drink heavily, and may also experience problems with substance misuse and mental health. In some cases, alcohol use may be overshadowed by substance abuse, which can result in poor recording of alcohol use during pregnancy.1 Alcohol consumption in pregnancy can cause significant fetal damage, all of which is preventable if the mother abstains.1

In Scotland, fewer children are diagnosed with FASD than would be expected from worldwide studies of similar populations. There are many possible reasons for under-diagnosis, including failure to consider PAE as a possible cause of neurodevelopmental delay and/or behavioural difficulties, resulting in missed opportunities to refer affected children for specialist assessment. Another reason is the lack of a standardised diagnostic approach, with associated training in its use. Professionals might also be reluctant to confirm the diagnosis if it is not obvious that the outcomes for the child will be improved by doing so.

SIGN 156 was developed as an adaptation of the 2016 Canadian guideline Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a guideline for diagnosis across the lifespan, with permission from the Canadian guideline developers.7 The SIGN guideline contains additional recommendations supported by the evidence review, and some adjustments of language to reflect the Scottish healthcare context.

Screening Pregnant Women for Alcohol Use

In general practice, alcohol use can be discussed during any consultation around contraception or women’s health. The Chief Medical Officers’ guideline recommends that all women should be advised not to consume alcohol in pregnancy (see Box 1).8

| Box 1: The Chief Medical Officers’ Guideline—Pregnancy and Drinking8 |

|---|

The Chief Medical Officers’ guideline is that:

The risk of harm to the baby is likely to be low if you have drunk only small amounts of alcohol before you knew you were pregnant or during pregnancy. If you find out you are pregnant after you have drunk alcohol during early pregnancy, you should avoid further drinking. You should be aware that it is unlikely in most cases that your baby has been affected. If you are worried about alcohol use during pregnancy do talk to your doctor or midwife. Department of Health, Welsh Government, Northern Ireland Department of Health, Scottish Government. UK Chief Medical Officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. DH, 2016. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf© Crown copyright 2016 |

A reliable and accurate maternal history is the best screening tool for determining the risk of FASD. It is crucial that service providers, particularly GPs, effectively and appropriately assess alcohol use in all women of reproductive age. A woman’s alcohol consumption during pregnancy can be influenced by a variety of factors, including:1

- prior alcohol use

- family history of alcohol use

- previous inpatient treatment for alcohol or substance use

- prior pregnancy resulting in a child with FASD

- lack of contraception, or unplanned pregnancy

- a history of mental health problems or abuse (physical, emotional, or sexual)

- low income and/or limited access to healthcare.

A sample FASD assessment form, which includes sections for recording maternal alcohol consumption in early pregnancy and standardised screening tools for alcohol exposure in pregnancy, is available for download from the SIGN website.9

When to Offer Interventions

While all women are advised not to drink alcohol during pregnancy, any woman of childbearing age found to be drinking in excess of the low-risk drinking guidelines for the general population should be offered early, brief interventions, which can easily become standard practice for GPs.8 A single, structured conversation is often sufficient, but referral to local counselling or other services, in some cases to consider detoxification or relapse prevention, may be appropriate for women with ‘risky’ drinking patterns.1

Appropriate tools for screening alcohol consumption in women in the antenatal period include T-ACE, TWEAK, and AUDIT-C,1,10 for which many general practice IT systems incorporate easy-to-use calculators. These tools do not require complex training, and recording of screening results is something that can easily become routine for GPs as well as other members of the team.

The use of biomarkers such as carbohydrate deficient transferrin and phosphatidylethanol might be considered in some circumstances,1 but generally these are not appropriate investigations in primary care.

Identifying Children At Risk of FASD Through Maternal Alcohol History

Diagnosis and subsequent management of children with FASD relies heavily on an accurate history of PAE, and SIGN recommends that all pregnant and postpartum women should be screened for alcohol use using validated measurement tools by professionals who have received appropriate training in their use.1

Confirmation of PAE requires documentation that the biological mother consumed alcohol during the index pregnancy (the pregnancy that relates to the child being assessed). This documentation can be based on:1

- reliable clinical observation

- self-report or reports by a reliable source

- medical records documenting positive blood alcohol concentrations, or

- a history of alcohol treatment or of other social, legal, or medical problems related to drinking during the pregnancy.

Identifying and Assessing Children Affected by PAE

When discussing a child who is experiencing developmental difficulties in any setting, GPs should consider the possibility of PAE, and investigate the mother’s drinking patterns during the index pregnancy.1 GPs may want to be especially alert to the risk if a child is ‘looked after’, fostered, or adopted as the biological mother’s drinking patterns may be unknown.

Due to the current under-recognition of FASD in Scotland, presentation may occur at a later stage. Some young people and adults present with neurodevelopmental dysfunction where PAE has not been considered as the underlying cause, many of whom may have developed secondary mental health problems, or become involved in the judicial system. GPs need to be aware of the increased prevalence of people affected by PAE in the mental health and judicial systems, as well as in looked after children and young people, and it is important to review and reassess patients in these groups.

Physical Features and Growth Impairment

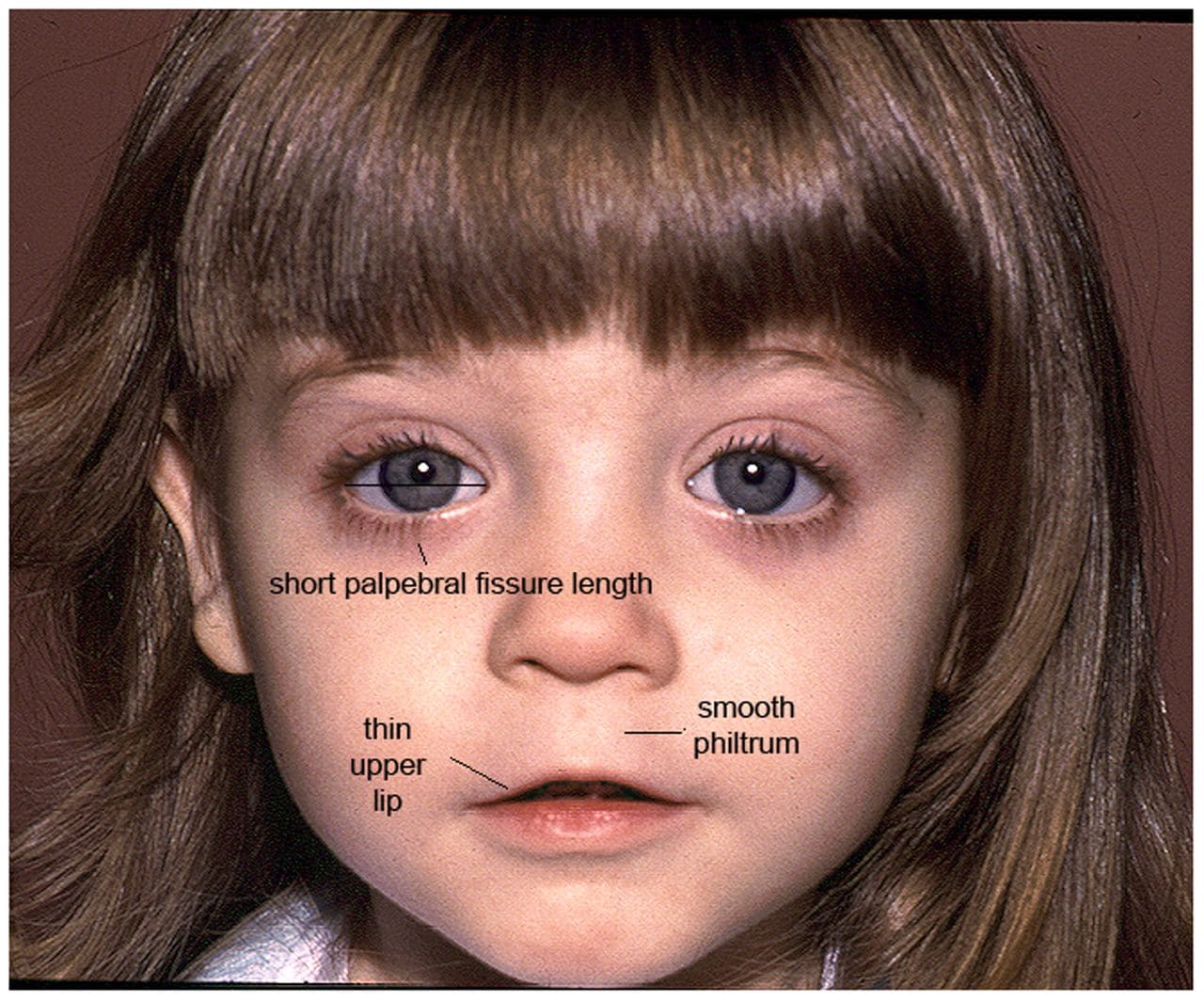

As diagnosis of FASD requires multidisciplinary assessment across a wide range of function, a final diagnosis of FASD cannot be made in primary care, but it is important to be aware of the signs. There are some specific physical features that raise suspicion that the patient has FASD (see Figure 1).1 The three key sentinel facial features of FASD are:1

- short palpebral fissures

- indistinct philtrum

- thin upper lip.

Child presenting with the three diagnostic facial features (short palpebral fissure lengths, smooth filtrum, and thin upper lip) of FASD.

FASD=fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

© 2019 Susan Astley Hemingway PhD, University of Washington. Reproduced with permission

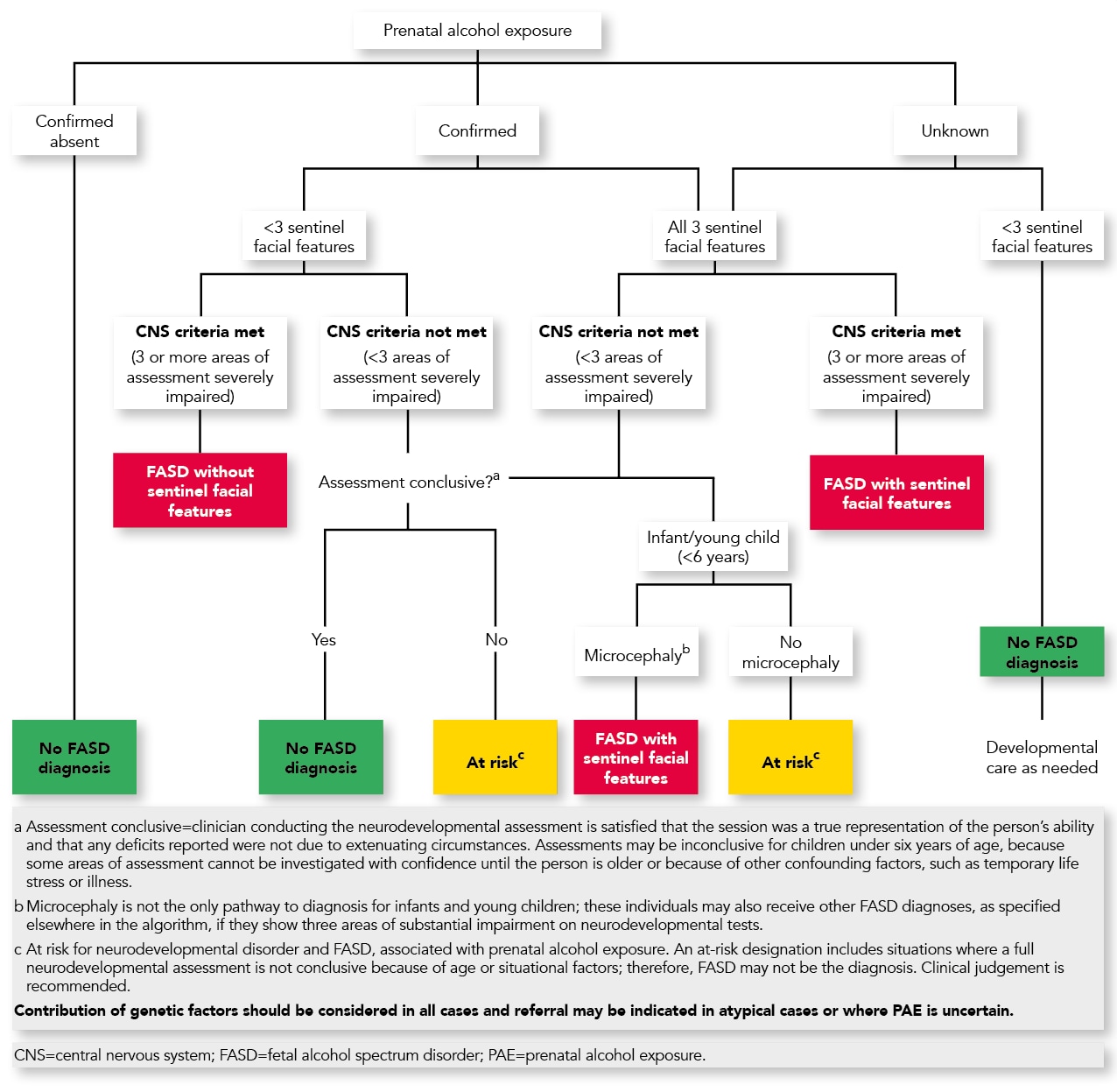

Awareness of these features might allow recognition of possible FASD and inform any decision to refer the patient onward. It should be noted that the sentinel facial features alone do not confirm (and are not necessarily required for) a diagnosis of FASD (see Figure 2).1,1

Growth measurements are also important, particularly head circumference in infants and young children to determine if a child has microcephaly (a head circumference two or more standard deviations below the mean). Diagnostic data of FASD indicate that the presence of all three sentinel facial features and microcephaly in children aged over 8 years is always associated with significant neurodevelopmental impairment. For this reason, children who have yet to meet the neurodevelopmental criteria for FASD can still be given a diagnosis if all three sentinel features and microcephaly are present.1

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol. Annex 2: diagnostic algorithm for FASD. SIGN 156. SIGN, 2019. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/assets/diagnostic_algorithm_for_fasd.pdf. Reproduced with permission.

Neurodevelopmental Impairment

Neurodevelopmental deficits are complex and influenced by multiple factors, and there is no single neuropsychological presentation specific to all cases of FASD. The variability of FASD is believed to be related to differences in the dose and timing of alcohol exposure during pregnancy, combined with genetic and environmental factors.1

Across the range of neurodevelopmental impairment, there is an infinite variety of possible presentations. GPs should be alert to the areas in which affected children and young people might be having difficulties, so that appropriate referrals for further investigations can be made. For ease of categorisation in the diagnosis of FASD, these have been divided into 10 areas of assessment:1

- motor skills

- neuroanatomy/neurophysiology

- cognition

- language

- academic achievement

- memory

- attention

- executive function, including impulse control and hyperactivity

- affect regulation, and

- adaptive behaviour, social skills, or social communication.

Other Factors

Hereditary, prenatal, or postnatal factors may also influence the developmental outcomes of a child, and these should always be accurately documented. In primary care we have the opportunity to gather this information from colleagues within the team, and are in a position to make the diagnostic process more efficient by presenting this information at referral.

Assessment and Diagnosis of Children At Risk of FASD

Diagnosis of FASD, with or without sentinel facial features, is made according the criteria in Box 2.1 A formal diagnosis of FASD can only be made where there is evidence of pervasive and long-standing brain dysfunction. In general practice, it is not practical for such thorough assessments to be carried out.

| Box 2: Diagnostic Criteria for FASD1 |

|---|

The term FASD was originally coined as an umbrella term to encompass a range of diagnoses (FAS, pFAS, FAE, ARND, ARBD) and the breadth of disabilities associated with PAE. With the evolution of FASD-related language within different professions, it is critical to adopt standardised terminology wherever possible. Standard terminology and definitions are important for comparing data across different geographical settings.

For both diagnoses:

a This has similarities to the diagnostic category FAS in ICD-10 and the diagnostic category ND-PAE in DSM-5b There is no equivalent diagnostic category in ICD-10 or DSM-5 FASD=fetal alcohol spectrum disorder; FAS=fetal alcohol syndrome; pFAS=partial fetal alcohol syndrome; FAE=fetal alcohol effects; ARND=alcohol-related neurodevelopment disorder; ARBD=alcohol-related birth defects; PAE=prenatal alcohol exposure; ICD‑10=International classification of diseases, 10th edition; ND-PAE=neurodevelopmental disorder–prenatal alcohol exposure; DSM-5=Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol. SIGN 156. SIGN, 2019. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/children-and-young-people-exposed-prenatally-to-alcohol/. Reproduced with permission |

The assessment of a child suspected of being affected by PAE involves a multidisciplinary team of suitable professionals, likely including:

- a paediatrician

- an occupational therapist

- a speech and language therapist

- a psychologist.

There is a large range of other health and social care professionals who can provide additional support, including geneticists and psychiatrists, among many others.

Parents or carers of a baby, child, or young person who is being referred for assessment of difficulties that might be related to PAE may well find this time very stressful and uncertain. The primary care team can help by:

- providing advice and information

- checking that they consent to the assessment

- informing them of what to expect, including:

- explaining what will happen at the assessment

- suggesting they may wish to bring someone with them to the assessment for support, for example, a friend or relative

- explaining that the assessment process may involve taking a photo of the child’s face and taking measurements.

Where infants and young children have a confirmed history of PAE and some indication of neurodevelopmental disorder, but do not meet the other criteria for FASD, they should be given the designation ‘at risk for neurodevelopment disorder and FASD, associated with prenatal alcohol exposure’. This designation can also be considered where infants and young children with a confirmed history of PAE have all three sentinel facial features, but do not yet have documentation or evidence of microcephaly or of abnormality in three or more of the neurodevelopmental areas of assessment.1

The ‘at risk’ designation can later facilitate specialist re-assessment and the information should be available to anyone who will be involved in childhood developmental surveillance and be recorded prominently in an individual’s records. It is crucial that GPs and colleagues in the primary healthcare team are aware of this information and its possible relevance as the child matures.1

Being assessed and given a diagnosis or descriptor of FASD can be helpful for the individual, their family, and service providers as a way of understanding the challenges associated with lifelong disability, which requires tailored support to achieve the best outcomes. The assessment should also help patients and those around them access interventions and support to address their biopsychosocial needs. The assessment should also inform the kind of advice the GP can provide to help them improve their general health and social wellbeing.1 Box 3 provides details of useful sources of information for patients, carers, and practitioners.

| Box 3: Useful Sources of Information for Patients, Carers, and Practitioners |

|---|

FASD Scotland offers information and awareness about the lifelong risks of prenatal exposure to alcohol as well as support and advocacy to families caring for a child affected by FASD. It provides strategies for managing FASD and training for professionals involved with individuals affected by FASD. Through partnership with other agencies it aims to prevent FASD and reduce secondary disabilities. National Organisation for Foetal Alcohol Syndrome-UK

The NOFAS-UK Helpline responds to enquiries from parents, family members, carers, and others needing advice or referrals for children with FASD disabilities. NOFAS-UK organises events focused on wellbeing for families and carers of children with FASD and provides resources that help support those with FASD at home and in school. FASD=fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |

After the Diagnosis

Following assessment and diagnosis, it is important that a member of the specialist team managing the child or young person’s condition follows up within a specified time interval to check that recommendations have been addressed, and to provide further support as necessary.1 GPs and other members of the primary healthcare team often have an important ongoing relationship with the individual and their family, and can advocate for people to access the support they need.

Where the assessment is made during adolescence or later, it is important to consider who else needs to be involved in the discussion of the patient’s assessment, and how best to present the findings. SIGN recommends providing education about the impact of FASD and appropriate support for the individual and those involved with their care;1 this is particularly relevant in primary care, where individuals and their families will often look to GPs for ongoing information and support. Discussions at this stage will also include the range of potential issues that might be expected to arise as a result of receiving the FASD diagnosis or descriptor. This information needs to be communicated in a culturally sensitive manner and using appropriate language.1 GPs are often well positioned to help address any issues that emerge, as they are likely to have comprehensive knowledge of both the individual and their family.

Management

Individuals with FASD and those caring for them should be advised about local resources that can improve outcomes. Sometimes these resources will be limited, but this is not a reason to avoid assessment or diagnosis.1 Often the identification of need will drive the development of resources, and it is likely that the growing understanding of this condition will uncover more unmet need.1

When young adults are transitioning to independent or interdependent living situations, they may need to be reassessed to identify changes in their adaptive function scores that could require adjustments to their management plan.1 This often coincides with a transition from child and adolescent mental health services to adult psychiatry, and other medical specialties involved in the person’s care may also need to arrange transition from children’s services to their adult equivalent. The transition process is another area where the continuity of primary care provides important support and reassurance.

Conclusion

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder can have a huge impact on neuropsychological development but frequently goes unrecognised. Primary care professionals should assess alcohol use in all women of reproductive age and advise women not to consume alcohol during pregnancy. It is important that clinicians are alert to the possibility of PAE in patients of all ages, as recognition and identification of specific problems can lead to targeted help and better outcomes for those affected. With the publication of this new guideline, SIGN aims to improve outcomes for children and young people affected by PAE through evidence‑based and consensus recommendations for assessment and diagnosis of FASD.

Dr Jenny Bennison

GP, Niddrie Medical Practice, Edinburgh

Vice Chair, SIGN

Member of the SIGN 156 guideline development group

| Key Points |

|---|

FASD=fetal alcohol spectrum disorder; PAE=prenatal alcohol exposure |

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; FASD=fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |