Jane Diggle and Dr Pam Brown Offer 10 Top Tips on Initiating Conversations about Weight and Motivating People to Make Healthy Changes

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

Overweight, obesity, and associated co-morbidities in the UK continue to rise; if current trends continue, projections that 50% of adults will be obese by 2050 will be realised.1

Brief interventions for smoking cessation and alcohol reduction are effective and demonstrate that healthcare professionals can successfully motivate people to change behaviour.2 Through talking openly and frequently about weight, including with people who are overweight, there is potential for similar impact to be achieved.

Obesity is a major risk factor for chronic diseases. When talking with people about weight, the focus should be on helping them to achieve the ‘hidden’ health benefits of weight loss, as well as visible weight loss, as this encourages realistic goals. It is also important to make people aware that cardiometabolic risk can be improved with diet and lifestyle changes, even if weight is not lost.3

Primary care clinicians are in an ideal position to help people make informed choices about their weight and their health long term, but as busy clinicians, it is easy to steer away from initiating conversations about weight. This article discusses a variety of resources and approaches, including brief interventions that are achievable in less than 2 minutes, with the aim of helping primary care clinicians to feel confident in starting conversations about weight and promoting the benefits of weight loss for people who are overweight or obese.

1. Initiate Conversations about Weight Frequently

It is usually down to the clinician to initiate the conversation but many people welcome the opportunity to talk about their weight. Raising sensitive subjects gets easier with practice; identify a few questions, try them out, and see what works. The Strategies to Overcome and Prevent (STOP) Obesity Alliance toolkit supports effective conversations about weight and health (available at: stopobesityalliance.org).4 Start with simple questions to make the patient comfortable:

- ‘Would it be okay if we discussed your weight?’

Linking the patient’s weight to the presenting complaint can make raising the issue easier:

- ‘You mentioned you have fatigue and aching knees, which may be related to excess weight. Would you like to talk about this to see if we can help you feel better?’

Many people are not ready to discuss their weight immediately, but will remember they were offered help and will return if and when they are motivated to tackle it.

2. Help People Understand Their Measurements

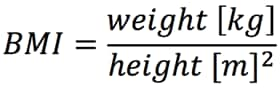

Share measurements in a familiar format (kilograms or stones/pounds, centimetres or inches), highlight the healthy range, and explain the health implications of the patient’s results. Overweight and obesity in adults is categorised using body mass index (BMI), see Table 1.5 Body mass index is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres.

Table 1: Obesity Classification Criteria5

| Classification | Body Mass Index (BMI), kg/m2 |

|---|---|

| Healthy weight | 18.5–24.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 |

| Obesity I | 30.0–34.9 |

| Obesity II | 35.0–39.9 |

| Obesity III | 40 or more |

| © NICE 2014 Obesity: identification, assessment and management. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/cg189. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | |

In children, BMI measurements are standardised for age and sex to account for variations in growth. BMI is plotted against age to find the BMI centile; a BMI above the 91st centile for the child’s age is defined as overweight, and above the 98th centile is considered obese.6 Childhood and adolescent (ages 2–20 years) BMI charts are available at: www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-03/boys_and_girls_bmi_chart.pdf

Explain that BMI does not differentiate between fat and lean body mass, so it can be misleading.7,8 For people with a BMI less than 35 kg/m2, waist circumference can be helpful as it correlates with visceral/intra-abdominal fat and cardiometabolic health risk (see Table 2),5,9 is easily measured, and changes more rapidly with weight loss than weight or BMI, so may be a useful motivator.7 For people with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, waist circumference does not add to the absolute measure of risk.5,10

Table 2: Waist Circumference and Cardiometabolic Health Risk5,

| Waist Circumference in Men (cm) | Waist Circumference in Women (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | South Asian, Chinese, Japanese | <90 | <80 |

| Caucasian | <94 | ||

| Increased risk | South Asian, Chinese, Japanese | ≥90 | ≥80 |

| Caucasian | 94–102 | 80–88 | |

| High risk | >102 | >88 | |

| This table has been compiled using data from NICE Clinical Guideline 189 Obesity: identification, assessment and management and NICE Public Health Guideline 46 BMI: preventing ill health and premature death in black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups. | |||

3. Explore with People why They Gain Weight

Explain that many factors contribute to weight gain, including genetics, lifestyle behaviours, inactivity, diet, medical problems, medications, quitting smoking, sleep deprivation, and hormones. Focus on finding things that the individual can change; help people to identify elements of an obesogenic environment (ready availability of calorie-dense foods, sedentary work/home life) and the impact it has on them.

Evidence of why people gain and lose weight is continuously evolving, so it is important to make people aware that recommendations for weight loss may change over time. Although weight gain occurs due to eating more calories than are ‘burnt off’ with activity, it is now clear that simply reducing the calorie intake and increasing activity does not necessarily lead to weight loss. Eating fewer calories results in a fall in basal metabolic rate as well as hormonal (ghrelin, leptin, insulin, glucagon), metabolic, and activity changes; the body’s mechanism designed to prevent harm from starvation.11 This helps explain why weight loss is so challenging. Additional changes may occur once obesity is well established, so changing behaviour earlier, when overweight, may be more successful.11

4. Challenge Common Beliefs about Diets

Prepare simple answers to topics commonly raised, such as the belief that fats cause weight gain. Fats do contain more calories per gram than proteins or carbohydrates, but excess dietary carbohydrates trigger the release of insulin, which causes the carbohydrates to be converted into fat through de novo lipogenesis. This process contributes to insulin resistance in muscles and tissues, and perpetuates further fat storage. Fat is no longer demonised, calorie counting is not recommended, and studies demonstrate slightly greater weight loss is achieved with low carbohydrate diets rather than the previously recommended low fat approaches.12

5. Share the Health Benefits of Weight Loss

Many people who are overweight or obese do not consider their weight to be a problem, so it is important to help them understand the health impacts of being overweight, including:13

- hypertension

- cardiovascular (CV) disease (myocardial infarction and stroke)

- type 2 diabetes

- some types of cancer

- musculoskeletal problems

- obstructive sleep apnoea.

Promote the readily perceived benefits of weight loss (feeling better, increased energy levels, sleeping better, improved mood, fewer aches and pains, improved mobility), as well as the hidden impact on cardiometabolic health, including reduced risk of all the conditions mentioned above.

A meta-analysis of diet weight loss studies (mainly low fat) demonstrated 18% significant all-cause mortality benefit in people who are obese and lose weight; bariatric surgery reduces mortality, CV disease, and some cancers.14

6. Assess the Patient’s Readiness to Change

‘Patient activation’ refers to the knowledge, skills, and confidence a person has in managing their own health and care. When people are supported to become more activated, they have better health outcomes, including the ability to lose weight.

NHS England has produced a quick guide on assessing a patient’s readiness to change and become activated towards self-care:15 www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/patient-activation-measure-quick-guide.pdf

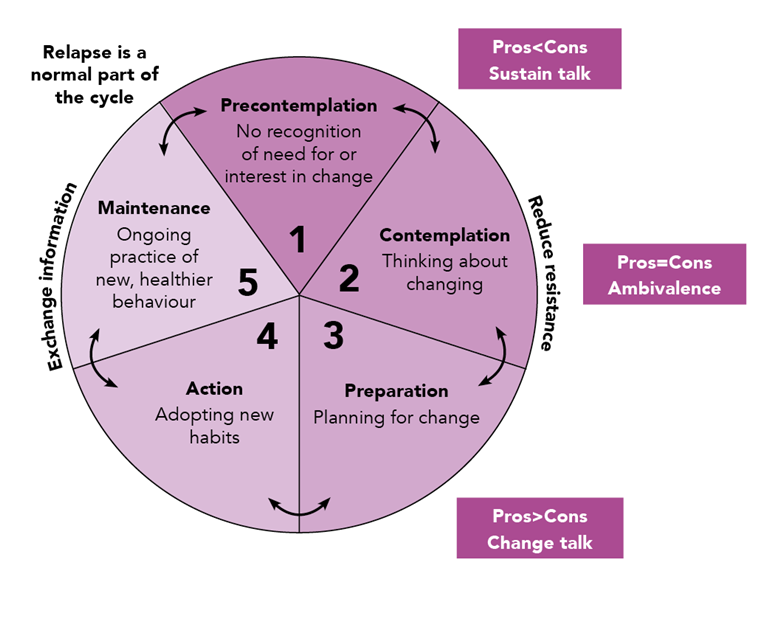

People typically move through a number of key stages of change when adopting new healthier behaviours (see Figure 1).16 When the patient is in the pre-contemplation or contemplation stages, discussions should be aimed at helping them move to the preparation stage.

Adapted from Prochaska J, Di Clemente C. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 1982; 19 (3): 276–288. Reproduced with permission.

Accurately identifying different stages of change comes with practice. When someone is still in the pre-contemplation stage it may help to highlight potential benefits of weight loss, but it is best to ask permission first. The ultimate aim is to elicit change talk coming from the patient—‘I’d like to lose weight’, ‘I could play with my grandchildren.’ Asking questions can be useful for assessing how important losing weight is to the individual and how confident they feel in achieving it.

For example:

- ‘On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 at the top, how important is it to you to lose weight?’

- following this up with ‘Why is it an 8 and not a 6?’ opens further discussion. Encouraging people to express personal, positive, emotional benefits of losing weight allows them to persuade themselves to choose to change. Capture their reasons for future discussions.

- ‘On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident are you that you could lose weight?’

- following up with ‘Why is it a 6 and not a 4?’ can help to explore their confidence

- ‘What would it take to move you to an 8?’ helps identify barriers, facilitate action planning and shared decision-making.

The STOP Obesity Alliance toolkit offers suggestions for exploring and moving through stages of change (see stopobesityalliance.org).4

7. Encourage People to Choose Sustainable Lifestyle Changes

Interventions for weight management include diet, physical activity, behaviour, drug therapy, and bariatric surgery. Remind people that reducing calorie intake and increasing physical activity can contribute to weight loss, but weight management is a complex issue so interventions must also address the psychological and emotional aspects.

There is insufficient evidence to support one weight loss dietary pattern over another. Encourage exploration of the person’s current eating habits to help them identify changes they might be willing to make. Often adherence predicts outcomes rather than diet chosen so encourage people to follow their choice of eating pattern. Studies suggest that low carbohydrate diets achieve slightly better weight loss than low fat diets over 12 months.12 Keep suggestions simple, such as:

- aim for more real food and less processed food, or

- consider a Mediterranean diet, or

- eat more fruit, vegetables, and fibre.

Simple advice is easy to incorporate in short discussions, and is especially effective if accompanied by links to websites or one-page leaflets. Commercial weight loss organisations provide more detailed guidance about weight loss.

Recommendations should guide people to making changes that improve cardiometabolic risk as well as weight loss. The Mediterranean diet reduces primary and secondary CV risk as well as weight. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is effective at reducing blood pressure. Variants such as 5:2 intermittent calorie restriction and time restricted eating (eating only during 10 hours or less) are anecdotally effective but studies are ongoing. Allowing people to decide which aspects of lifestyle they want to discuss using a bubble diagram (see Figure 2), and individualising discussions, can increase ownership and empower people to make changes.

Bubble diagrams can be used to help patients decide which aspects of their lifestyle they want to discuss. the blank bubbles allow people to tailor the discussion to their own needs so that they do not feel it is being driven solely by the healthcare professional.

Many people believe that drugs are an easy route to weight loss. Orlistat is the only drug available on NHS prescription that is licensed for treatment of obesity. Treatment with orlistat should be discontinued after 12 weeks if patients have been unable to lose at least 5% of the body weight as measured at the start of therapy.17 Liraglutide 3 mg and other drugs have demonstrated efficacy but are not currently (February 2019) available on the NHS for treatment of obesity.18–22

8. Help People Understand the Benefits of Physical Activity

Physical inactivity and prolonged sitting are modifiable risk factors for mortality and morbidity.23 Being active improves cardiometabolic risk, so people without contraindications should be encouraged to aim for 150 minutes of moderate activity every week (or 75 minutes of vigorous activity), as well as strength exercise on at least 2 days per week.24

Help the patient to identify activities they enjoy, encourage walking, and discuss ways of building activity into daily life to help people become more active. Record activity level using a validated tool such as the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire.25 Refer to Exercise on Prescription and ‘Green Gym’ schemes to help motivated people to adopt active habits. Some practices partner with initiatives like Walking for health or parkrun to provide additional options for ‘prescribing’ exercise.

Many people believe that inability to exercise (through lack of time or musculoskeletal problems) makes weight loss impossible. However, physical activity is less effective as a sole weight loss strategy than diet, although it can reduce visceral fat and insulin resistance,26–28 and in combination with diet only increases loss by around 1.5 kg compared with diet alone.29

9. Help People Set Realistic Goals and Support Progress

People often have unrealistic weight loss goals and set themselves up for certain failure. Discussing realistic goals (including hidden health benefits) encourages people to feel successful and avoid disappointment and demotivation. Encourage SMART—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time‐sensitive—goals, which may be used to create meaningful action plans.

Regular weighing by healthcare professionals or in commercial programmes can support weight loss, so keep weighing scales and tape measures readily accessible. Recording weight and waist circumference helps track, and provide feedback on, progress. Slow, steady or rapid weight loss are both beneficial; speed of loss does not significantly influence weight regain as was previously believed.30

Achieving and maintaining weight loss of 3–5 kg (or 5% body weight) has significant health benefits, whereas attaining ideal weight or BMI is unrealistic for most. The recent DiRECT study demonstrated that losing 10–15 kg can result in remission of type 2 diabetes at 1 year.31

10. Signpost to Help and Support and Know your Local Pathways

Healthcare professionals are often put off starting a conversation about weight due to lack of confidence in weight management, but most of the time the main role is in signposting people to other information, organisations, and resources. Commercial weight loss organisations may be more effective at helping people lose weight and maintain loss than practice teams.32 Check if you can refer patients at preferential rates to services in your local area.

Learn about your local obesity care pathway and Tier 2 and 3 services, so you can refer appropriate patients.

Discuss bariatric surgery with those who meet local criteria. The conversation should include the types of surgery and significant weight loss and health benefits. People often believe that they can continue to eat normally after surgery, and sharing the restrictions and potential side-effects often motivates re-engagement with medical management.

Sources of further information for healthcare professionals can be found in Box 1.

Jane Diggle

Specialist Practitioner Practice Nurse, South Kirkby, West Yorkshire

Dr Pam Brown

GP with special interest in diabetes, obesity, and lifestyle medicine,Swansea

| Box 1: Sources of Information about Managing Overweight and Obesity in Primary Care |

|---|

NICE Clinical Guideline (CG) 189 on Obesity: identification, assessment and management (www.nice.org.uk/cg189) NICE Public health guideline (PH) 53 on Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults (www.nice.org.uk/ph53) Stop Obesity Alliance (stopobesityalliance.org) Diabetes UK. Meal plans and diabetes. www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/enjoy-food/eating-with-diabetes/meal-plans- Diabetes UK. Evidence-based nutrition guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes.www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/food-nutrition-lifestyle/evidence-based-nutrition-guidelines-for-the-prevention-and-management-of-diabetes |