Dr Rachel Pryke Presents a Summary of Consensus Guidance that Aims to Help Practitioners in Primary Care to Support Patients Living with Obesity with Weight Management

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

Obesity is associated with developing a number of long-term conditions and puts patients at risk of poorer physical and mental health outcomes, as well as impacting on the NHS in terms of increased hospital admissions.1 This has been demonstrated during the coronavirus pandemic—people living with overweight and obesity (a body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2) are not considered to be at increased risk of catching coronavirus, but they are at increased risk of worse outcomes from COVID-19.1–3 Adipose tissue releases inflammatory cytokines that potentiate the inflammatory response to infection, and insulin resistance increases endothelial and platelet dysfunction, which adds to the vascular inflammation and increased thrombotic risk from the virus.3 Addressing obesity will therefore help to improve outcomes from COVID-19 as well as many other health indicators.3

In July 2020, the UK Government introduced a set of policies to support people to achieve and maintain a healthy weight and to encourage the NHS to focus on public health and prevention, in order to improve the health outcomes of people with obesity and to alleviate the resulting strain on the NHS.1

A multidisciplinary working party was convened by Guidelines in October 2020 to develop consensus guidance on managing obesity in primary care to improve the care of people with obesity in the UK.4 The consensus guidance was developed by a multidisciplinary expert panel with the support of an educational grant from a pharmaceutical company (refer to the guidance document for further details).4 This guidance aimed to give an overview of best practice in weight management for patients with obesity, to enable primary care healthcare professionals to:4

- feel confident about raising discussions about weight management with patients with obesity

- understand how to avoid blame, stigma, and prejudice in conversations about obesity

- carry out holistic, health-centred assessments of patients with obesity, instead of a more traditional weight-centred approach

- be clear about their role in managing obesity and know when and where to refer patients for specialist treatment

- support patients with obesity, including those who have undergone bariatric surgery, to follow a long-term weight management plan.

The consensus guidance reflects rapid changes in obesity research, appreciation of the metabolic burden created by obesity in patients with COVID-19 and, above all, the need to address historically stigmatising attitudes and understand the realities of living with a complex, chronic relapsing condition that impacts across the spectrum of co-morbidities.4

Role of Primary Care

As primary care gears towards increasing patient partnership models of care, understanding the most efficient and effective parts of the GP’s role, including offering emerging treatment options, is an important aspect of helping people with obesity to be part of the therapeutic team. It is important to understand the unique role of primary care in obesity management, particularly the aspects that other healthcare and allied professionals are less able to carry out, as well as those that primary care professionals should steer away from (see Box 1).

| Box 1: Roles and Remit of Primary Care in Obesity Management |

|---|

Unique roles undertaken in primary care by GPs and practice nurses include the following:

Areas where evidence is lacking for a primary care role include:5,6

|

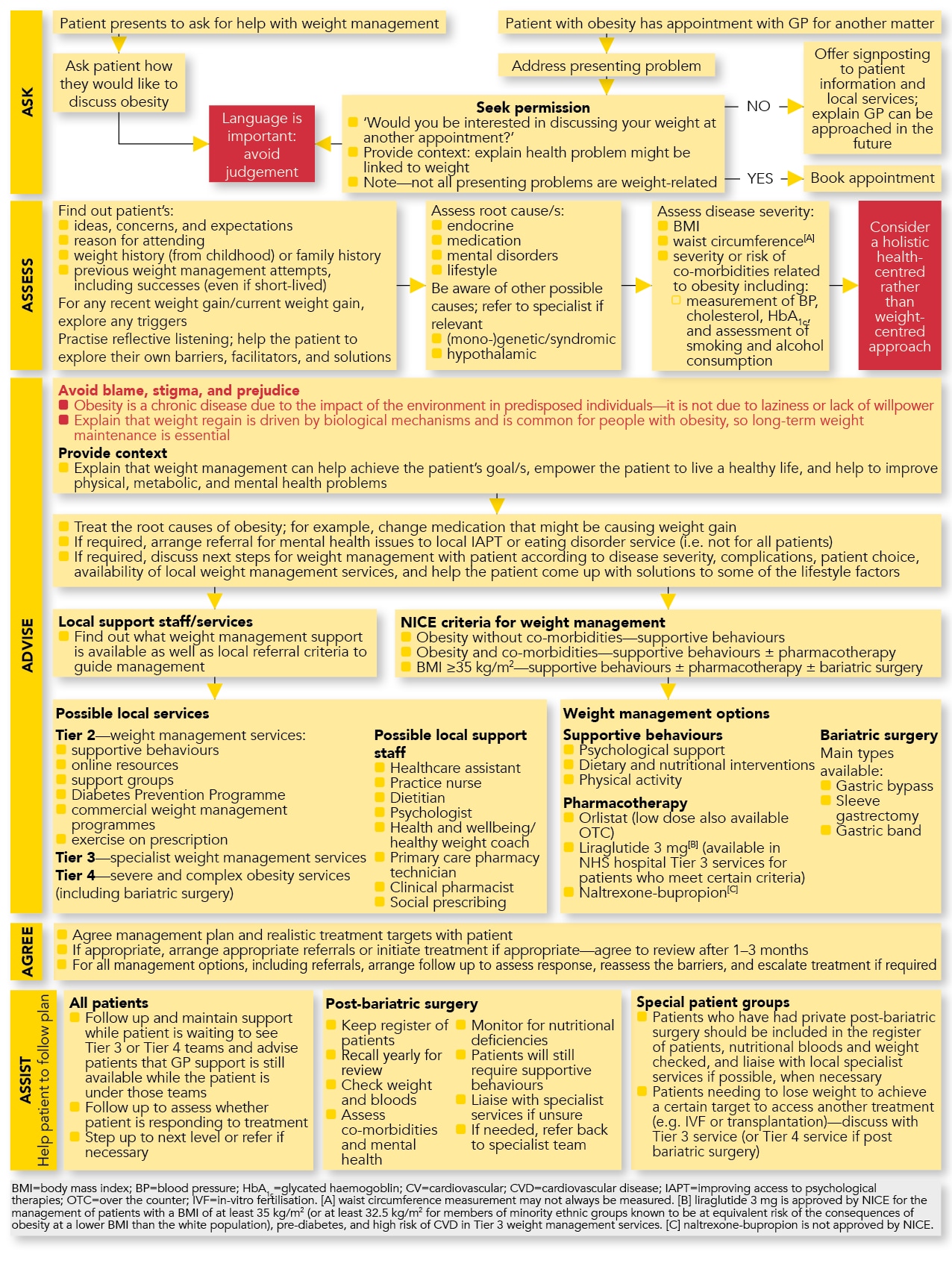

The consensus guideline4 includes a useful algorithm (see Figure 1) that summarises the primary-care-relevant aspects of obesity management, using the 5As model: ‘Ask, Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist.’ Some essential points from each of these aspects of obesity management are discussed in more detail below.

Ask

When considering how best to broach conversations about obesity, it is useful for practitioners to keep in mind the 3Cs:

- check that phrasing does not automatically convey judgement—this is a common pitfall where discussions can go wrong; never assume that someone with obesity is not already engaged in making changes, and avoid sentences starting with phrases such as ‘I think’ or ‘You ought’

- consider whether now is the right time, and whether the agenda being raised is a pressing concern to the person with obesity

- create an invitation into the discussion—asking permission (‘Would it be ok to talk about your weight?’) or starting with the patient’s feelings (‘How do you feel about your weight at the moment?’) opens up choice over engagement and encourages starting with the patient’s perspective.

Assess

Starting off positively, and showing a wish to listen rather than lecture, often enables the patient’s priorities to quickly emerge.7 To create a holistic health-centred rather than weight-centred approach, discussions should explore the patient’s barriers, facilitators, and solutions, along with the patient’s wider health concerns, co-morbidities, family dynamics, and historical relationship with food, dieting, and lifestyle.

A pattern of repeated weight loss and relapse, reflecting the chronic nature of obesity, can indicate biological mechanisms including genetic predisposition that is hard to alter and may result in motivational collapse, yet can still be positively influenced.8 Planning how future approaches to weight management may differ to what the patient has tried previously is an important part of the conversation, which may relate to altering expectations or trying new therapeutic approaches.8

Advise

Giving advice is a core component of primary care consultations. Training in motivational interviewing techniques teaches us that telling people what to do often results in the opposite; people dig in their heels and find reasons why every suggestion will not work (much like how nuclear threats of confiscating electronic devices from teenagers will often fail to result in their bedrooms being tidied or personal hygiene attended to).7

Effective approaches include seeking solutions from patients living with obesity themselves, for example: ‘What ideas do you have that you might want to try? ’.

To build on this, practitioners should convey confidence where evidence demonstrates effectiveness, for example: ‘Would you like me to tell you more about some effective options you could consider? ’. Examples include highlighting support through the Diabetes Prevention Programme, signposting to weight management support groups, exploring physical activity opportunities, explaining medication options, or referring through the local metabolic treatment pathway to tier 3 or 4 services.

NICE recommends that orlistat can be prescribed as part of an overall plan for managing obesity in adults who meet specific criteria.2 However, there is another therapy, liraglutide, that has been approved recently by NICE for managing overweight and obesity in some patients,9 which has to be prescribed in secondary care by a specialist multidisciplinary tier 3 weight management service; this gives a new reason for GPs to consider referral to tier 3 clinics.

It is important to double-check potential barriers to the options a patient is considering. Helpful considerations for the practitioner to work through with the patient are: what might make it difficult, how strong is the patient’s motivation to ‘make it happen’, and what might facilitate the patient committing to a plan. The algorithm outlines an array of treatment options (see Figure 1).

Tahrani A, Parretti H, O’Kane M et al. Managing obesity in primary care. In: Hatton S, editor. Guidelines – summarising clinical guidelines for primary care. 77th ed. Chesham: MGP Ltd; December 2020. pp.195–199.

A particularly topical question relates to whether to recommend low carbohydrate diets for people with type 2 diabetes. The evidence was extensively scrutinised in 2020 by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN).10 The draft conclusions of the committee’s review are:

- for body weight, there is no overall difference between lower and higher carbohydrate diets in the long-term (at or beyond 12 months)

- for blood glucose (sugar) levels, lower carbohydrate diets may have benefits over higher carbohydrate diets in the short term, but their longer-term effects are unclear, based on the evidence considered.

The SACN review showed that short-term benefits from carbohydrate restriction were difficult to maintain, with the evidence revealing that all dieting regimens tended to merge over time.10 People with type 2 diabetes are currently advised to follow healthy eating advice for the general population. Current UK Government advice (represented by the Eatwell Guide)11 is that for the general population, around four-tenths of total dietary energy should be from starchy carbohydrates (such as potatoes, bread, and rice), opting for higher fibre or wholegrain versions where possible. SACN’s conclusions support flexibility in patient choice—where a patient with obesity is interested in trying a low carbohydrate diet there is evidence to be supportive, but other forms of calorific control produce similar outcomes over time. The important step is to help patients to engage, and to re-engage repeatedly over time, with making healthier dietary choices, including portion control, and to combine this with physical activity approaches wherever possible.

Agree

The goal-setting element is a crucial part of ensuring that people with obesity are not setting themselves up to fail by checking with them that their goals are realistic and timely. The way progress is measured can be broadened; BMI reduction may be overly narrow as well as challenging, so consideration should be given to additional signs of progress such as improvements in dietary quality, changes in activity levels, or reductions in medication to control co-morbidities. Tangible direct goals that the person can track themselves should be encouraged, for example, how often a physical activity happens per week, or how many portions of fruit and vegetables are eaten daily, rather than indirect goals such as a drop in cholesterol.

Assist

Follow up is a sometimes overlooked element of support, reflecting the challenges of continuity of care and competing health concerns presenting to primary care. The algorithm provides a summary of key aspects that can help people follow their agreed plan (see Figure 1).

An emerging need is for primary care to be prepared to give long-term support to patients after bariatric surgery procedures. Surgical care packages typically last for a maximum of 2 years but lifelong monitoring is required (regardless of whether care was done privately or through the NHS) to avoid the risk of nutritional deficiencies and to oversee co-morbidity management, compliance with nutritional supplements, and to support ongoing engagement with a healthy lifestyle. Post-metabolic surgery review is best combined with annual co-morbidity review, and templates are available at some practices to support a coordinated and efficient review. Further guidance is available from the Royal College of General Practitioners.12

Addressing Stigma

Living with obesity is often a lifelong journey, and sometimes originates in early childhood, affecting a person’s life choices as well as relationships over time. It is important to recognise that harm stemming from obesity stigma may have accumulated over many years, from feelings of being judged and discriminated against personally and by society as a whole, as well as from personal feelings about body image, guilt, a sense of failure, or low self-confidence.8 Acknowledging these feelings and concerns, and the difficulties of altering weight, can demonstrate the practitioner’s respect and desire to understand how the world feels from the perspective of people living with obesity. Starting with positive and sensitive conversations is an important step in helping people with obesity to manage their weight.

Summary

The consensus guidance discussed in this article reflects rapid changes within obesity research, including the effects of obesity in patients with COVID–19. The guidance also highlights the need to address historically stigmatising attitudes, and includes practical advice for primary care healthcare professionals on how to support patients with obesity who are looking to manage their weight and adopt a healthier lifestyle.

Dr Rachel Pryke

GP, Worcestershire

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Clinical Advisor on obesity and multimorbidity

Strategic Centre for Obesity Professional Education (SCOPE) World Obesity Clinical Care Committee Member

Founder of the RCGP-affiliated GPs with an Interest in Nutrition Group (GPING)

| Key Points |

|---|

|

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; QOF=quality and outcomes framework |