Dr Alix Rolfe Explores the Updated Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Recommendations on Epilepsy in Children and Young People

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

Epilepsy is the most common serious neurological condition of childhood—in the UK, the condition affects an estimated 112,000 children and young people aged less than 19 years,1 and can have a significant impact on quality of life. It is a disease in which the patient experiences recurrent seizures due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain, which can present clinically as a disturbance of consciousness, behaviour, cognition, emotion, motor function, or sensation.2 There are many different types of epilepsy, which have varying clinical presentations, diagnostic criteria, and management.

In May 2021, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) updated SIGN 159, Epilepsies in children and young people: investigative procedures and management, with the aim of ensuring that children and young people with epilepsy are investigated properly, receive the correct management, and are provided with appropriate information on epilepsy, comorbidities, and risk of mortality.3 Central to the development of this guideline were the views and concerns of patients, their families, and their carers—significant time was spent undertaking a literature search to identify issues of importance to these groups, as well as encouraging the involvement of young people with epilepsy and third-sector organisations, and the information gleaned fed into the guideline recommendations.

One of the most important factors identified by patients that influences satisfaction with care was ‘ease of access’ to both primary and secondary care services for epilepsy.3 Although much of the care provided to people with epilepsy is undertaken by specialist epilepsy services, it is important for primary care to have an understanding of the presentation and management of epilepsy, especially the issues that may lead patients to present to primary care, such as discussions about contraception or psychiatric complications of epilepsy. Many GPs and community pharmacists are likely to be involved in the prescribing of medications to patients with epilepsy.

This article discusses the recommendations of SIGN 159, and explains the role of primary care in supporting children and young people with epilepsy.

Assessment and Diagnosis

Although many people will present to the emergency department following a seizure, especially if it is tonic–clonic or prolonged in nature, some patients with more subtle seizures, such as spasms and absence seizures, first attend primary care. In the author’s clinical experience, when a child or young person presents with a potential seizure, ideally, a face-to-face assessment is required. A thorough history should be taken, from the patient and a witness if possible, and should include the clinical features of the event, including what happened before, during, and after the potential seizure.3 Were there any symptoms suggestive of an aura?3 What were the features of the seizure?3 How was the patient after the seizure?3 If more than one seizure occurred, were they similar?3 For assessment of the seizure itself, a video recording should be taken, if possible, and uploaded using a secure video transfer system.3

Clinicians should enquire about potential triggers, such as sleep deprivation, stress, light sensitivity, or alcohol use, and residual symptoms, such as drowsiness, headaches, amnesia, or confusion (which usually occur only after generalised tonic and/or clonic seizures).4 Patients should also be asked about any risk factors suggesting a predisposition for epilepsy,4 including:5

- premature birth

- complicated febrile seizures

- genetic conditions known to be associated with epilepsy, such as tuberous sclerosis or neurofibromatosis

- brain development malformations

- a family history of epilepsy or neurological illness

- head trauma, infections, or tumours

- comorbid conditions, such as cerebrovascular disease and stroke

- neurodegenerative disorders.

Also of importance is any developmental regression or poor educational attainment.3

A physical examination should include cardiac, neurological, and mental state examinations, and a developmental assessment if appropriate.4 Consideration should also be given to examining the mouth to look for lateral tongue bites, and examining the patient’s body to identify any injuries sustained during the seizure.4

To avoid misdiagnosis, the definitive diagnosis of epilepsy should be made by a specialist.3 Therefore, all children and young people with suspected epilepsy should be referred urgently to a specialist with expertise in epilepsy,6 but primary care healthcare professionals may consider arranging baseline blood tests, such as full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, and calcium.4 The 2021 NICE Clinical Guideline 137, Epilepsies: diagnosis and management, and the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on epilepsy provide further useful guidance and algorithms on the initial management of suspected epilepsy.6,7

SIGN uses the 2017 International League Against Epilepsy classification system for seizures and epilepsy syndromes (www.ilae.org). A summary of the specific features of different types of seizure is provided in Box 1.4

| Box 1: Specific Features of Seizures4 |

|---|

© NICE 2021. Epilepsy: how should I assess a person presenting with a first seizure? cks.nice.org.uk/topics/epilepsy/diagnosis/assessment/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Hospital Assessment

The patient will undergo further assessment by the specialist clinic, but it is useful for the primary care team to be aware of the form this may take. Once a clinical diagnosis has been made, the patient should have an electroencephalogram to further classify the type of epilepsy because this has significant implications for management and prognosis.3 Depending on the cause of epilepsy, the patient will most likely undergo neuroimaging; magnetic resonance imaging is the modality of choice, and should be performed in all children and young people with epilepsy except those with genetic generalised epilepsy and childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes.3 Genetic causes of epilepsy should be considered and discussed and, with appropriate counselling, genetic testing should be offered to families of all children and young people presenting with epilepsy for whom aetiology cannot be fully explained through history, examination, targeted metabolic tests, or neuroimaging.3

The epilepsy specialist and specialist nurse should then provide appropriate information and discussion time about the diagnosis for the patient, their family, and their carers.3

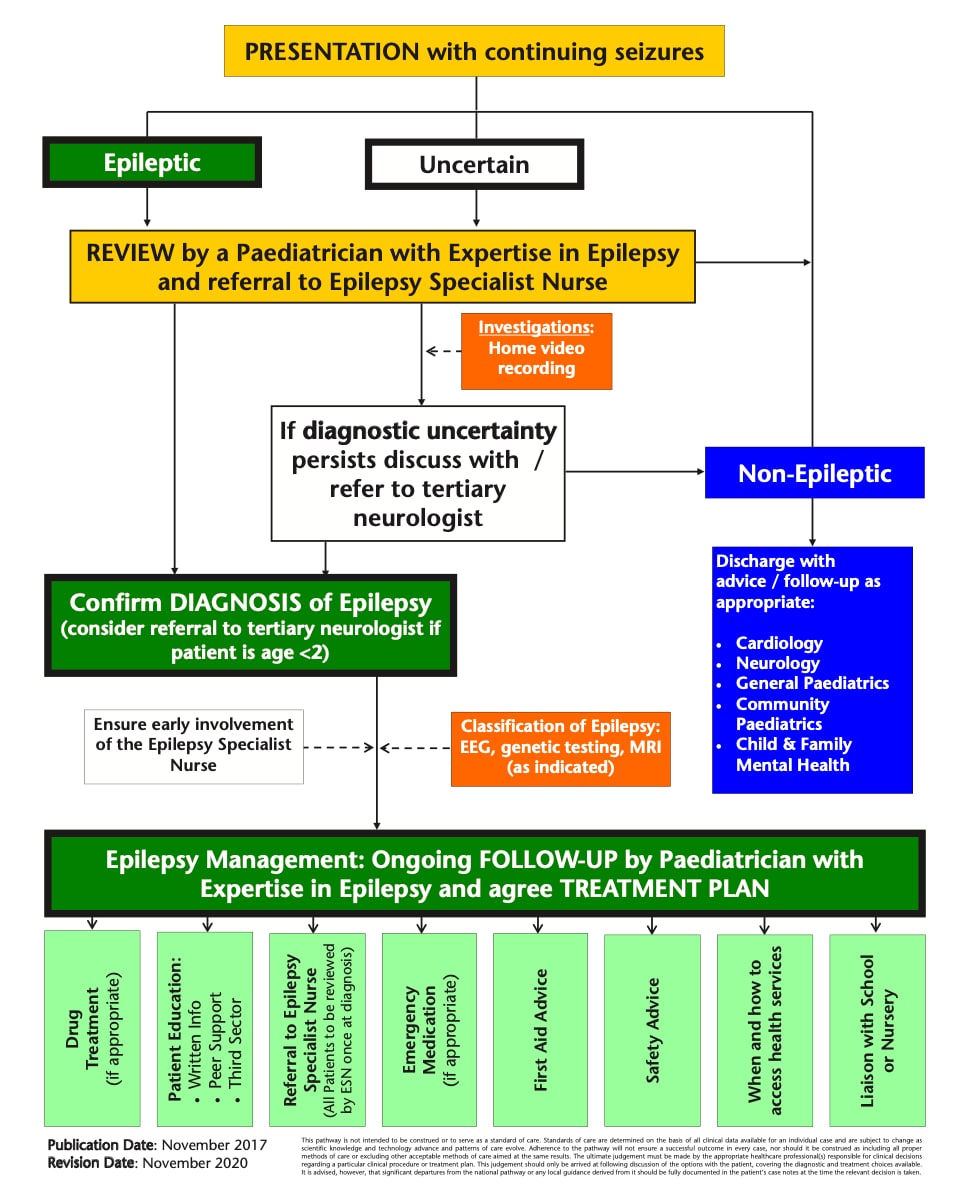

Figure 1 shows the Scottish Paediatric Epilepsy Network pathway for the diagnosis and initial management of epilepsy.3

SPEN=Scottish Paediatric Epilepsy Network; EEG=electroencephalogram; MRI=magnetic resonance imaging; ESN=epilepsy specialist nurse

© Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2021. Epilepsies in children and young people: investigative procedures and management.www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/epilepsies-in-children-and-young-people-investigative-procedures-and-management/ Reproduced with permission.

Management

Anti-epileptic Drugs

Pharmaceutical treatment with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) is the first-line and mainstay treatment for children and young people with epilepsy, and aims to achieve seizure freedom or reduction, in turn decreasing hospital admissions, reducing morbidity and mortality, and improving quality of life.3 The choice of AED should be agreed by the young person, their family and carers, and the epilepsy specialist.3 Treatment options should be discussed by the specialist with the patient and their family and carers, and written and verbal information should be provided on aspects such as:3

- choice of drug

- efficacy

- side effects (which have been reported in 31% of children and young people taking AEDs, and include behavioural changes and drowsiness)

- adherence, including how it should be taken

- dosage

- drug interactions.

Some patients may require an adjunctive AED if two first-line therapies have been tried and epilepsy remains poorly controlled or the therapy is not tolerated,3 which increases the risk of side effects. The recommended medications for different epileptic syndromes are discussed in detail in the SIGN guideline.3 It is important to note that the epilepsy specialist may not be aware of any other medications prescribed to the patient.

Ketogenic Diet

If epilepsy is drug resistant, nonpharmaceutical treatments, such as a ketogenic diet, can be trialled.3 A ketogenic diet is a diet that is high in fat and low in carbohydrate, and aims to induce ketosis.3 The patient’s AED medication can be changed from liquid to tablet form to reduce its sugar content, and it is very important to adopt a multidisciplinary approach involving an experienced dietitian because patients can struggle with adherence.3 Further information about the ketogenic diet can be found on the Epilepsy Society website.8

Surgery, Vagus Nerve Stimulation, and Deep Brain Stimulation

A small number of patients may be eligible for surgery or vagus nerve stimulation as part of the treatment for their epilepsy, especially if their condition is drug resistant.3 The patient will be assessed for their eligibility for these procedures by the secondary care epilepsy team. Deep brain stimulation should not be used in the paediatric population—further research is required before recommendations can be made on its use in children and young people.3

Contraception

Specific consideration must be given to contraception and pregnancy in all female patients of child-bearing age with epilepsy, and this is likely to be one of the main reasons that a patient with epilepsy attends primary care. Epilepsy does not itself restrict the use of contraception, but the medication used to manage it can have significant effects, in particular teratogenicity and reducing the efficacy of contraception.9 Conversely, progesterone-only contraceptives can interact significantly with lamotrigine, increasing the risk of neurotoxicity.9 Sodium valproate should not be prescribed to female patients of child-bearing potential with epilepsy unless they are part of a pregnancy prevention programme.3,10

Ideally, the conversation about contraception should occur before the patient is sexually active,9 and should be conducted by the specialist team, who will then be able to advise primary care prescribers. Guidance regarding AEDs and pregnancy has been produced by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.10 Any female patient with epilepsy who is planning to become pregnant should be prescribed 5 mg of folic acid daily before any possibility of pregnancy, and referred to their epilepsy team to discuss pregnancy planning further.10

Cognitive, Developmental, and Psychiatric Comorbidities

The prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, is significantly higher in children and young people with epilepsy; this should be considered, and the patient referred to the appropriate services.3 In addition, there is a higher risk of cognitive and academic impairments in this population, even in those whose epilepsy is considered benign or well controlled.3

Psychiatric disorders are also more common, and should be considered in this group of patients.9 This is especially important during the teenage years and into young adulthood. Suicide rates are three times higher in patients with epilepsy compared with the general population.9 Anxiety is evident in 11–50% of children and young people with epilepsy.3 Therefore, healthcare professionals should routinely enquire about anxiety and depression, and these questions should be directed at the young person rather than their parents or carers.3 Depression in young people with epilepsy can be managed with cognitive behavioural therapy or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)—but, if the patient is aged less than 18 years, SSRIs should be initiated by a specialist,11 and consideration should be given to interactions between medications, although there is no evidence to suggest that SSRIs are associated with a significant increase in seizure activity.3

Transition

The transition between paediatric and adult services can be a difficult time for patients with epilepsy and their families and carers. It is a time of change, when patients are encouraged to become more independent and empowered over their care.3 There is a risk of a lack of adherence to medication, reduced attendance at regular reviews, and the emergence of psychological comorbidities.12 Hence, patients should be supported through the transition in a planned and structured way, and offered age-appropriate lifestyle advice on adult life, covering topics such as how to make an appointment, order a prescription, and collect medication, and providing information on sexual health, drugs, and driving.3

Mortality

The risk of death in children and young adults with epilepsy is significantly greater than in the general population.3 This may be the result of complications of seizures, status epilepticus, accidental death, mental health issues, suicide, underlying neurological conditions, or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).3 It is important that verbal information about SUDEP, with supporting written information, is provided face to face by the specialist team at the time of diagnosis.3 Crucial to reducing deaths in patients with epilepsy is ensuring optimum seizure control and providing specific guidance on bathing, water sports, and heights.3 Further information about SUDEP and support for families can be found on the SUDEP Action website.13

Summary

Although the majority of the care provided to children and young people with epilepsy is delivered by specialist services, patients with epilepsy will often be seen in primary care for other issues—this is why it is important to be aware of the risks they face regarding anxiety and depression and, in the case of female patients of child-bearing age, contraception. Primary care also has an understanding of the situational context of the patient, their family, and their carers, and the other difficulties that they may face.

It is important to understand the potential side effects of anti-epileptic medication, and the consequences of lack of adherence to this medication if infrequently requested. It is also useful to know where to signpost patients and their parents and carers to find out more about epilepsy. Patients often prefer to talk to their specialist epilepsy nurse or someone from a voluntary organisation rather than their GP, but they also place great emphasis on having GPs that they find approachable and knowledgeable.3

| Key Points |

|---|

AED=anti-epileptic drugs |

| Useful Resources |

|---|

Scottish Paediatric Epilepsy Network—www.spen.scot.nhs.uk Epilepsy Action—www.epilepsy.org.uk Epilepsy Research UK—www.epilepsyresearch.org.uk |

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system |

Dr Alix Rolfe

GP Partner, Colinton Medical Practice, Edinburgh