Professor Ian Giles and Professor Caroline Gordon Describe Best Practice in the Care of Women of Child-bearing Age with Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases Before, During, and After Pregnancy

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

Improved treatments for inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRDs) mean that many women with these diseases are achieving disease control, so are more likely to be considering pregnancy and asking their healthcare professionals for appropriate advice.1,2 Data on the effect of pregnancy on rheumatic diseases are conflicting, with some studies reporting improvements in disease activity and others the opposite.1,3 It is clear, however, that active rheumatic disease is associated with a number of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as fetal loss, fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia, complications of labour, and venous thromboembolism (VTE).1,4 Therefore, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) compatible with pregnancy are required to control disease activity to ensure positive pregnancy outcomes.1,2,4

Women with IRDs should be counselled that maintenance of disease control with treatment that is compatible with pregnancy increases positive outcomes for mother and baby.1 This counselling is vital to ensure their adherence to prescribing recommendations.

Published evidence-based guidelines5–11 advise on the management of IRDs in women of child-bearing age and discuss appropriate drug usage during pregnancy. Many of the recommended drugs, however, are not licensed in pregnancy and breastfeeding so may be withdrawn from pregnant women unnecessarily,12 thus increasing the risk of increased disease activity during pregnancy.13

A multidisciplinary working party has produced a guideline, Best practice management of women of child-bearing age with inflammatory rheumatic diseases,14 which has been developed for healthcare professionals to advise on the holistic management of women of child-bearing age with IRDs. The working party guideline14 aims to:

- highlight existing guidance

- improve discussions about reproductive health and perceived risk of DMARDs to pregnancy versus the risk of disease activity

- empower healthcare professionals to prescribe drugs that will ensure disease control and positive pregnancy outcomes

- encourage conversations about contraception

- consider the timing of pregnancy with respect to disease activity and thus increase adherence to ensure positive pregnancy outcomes.

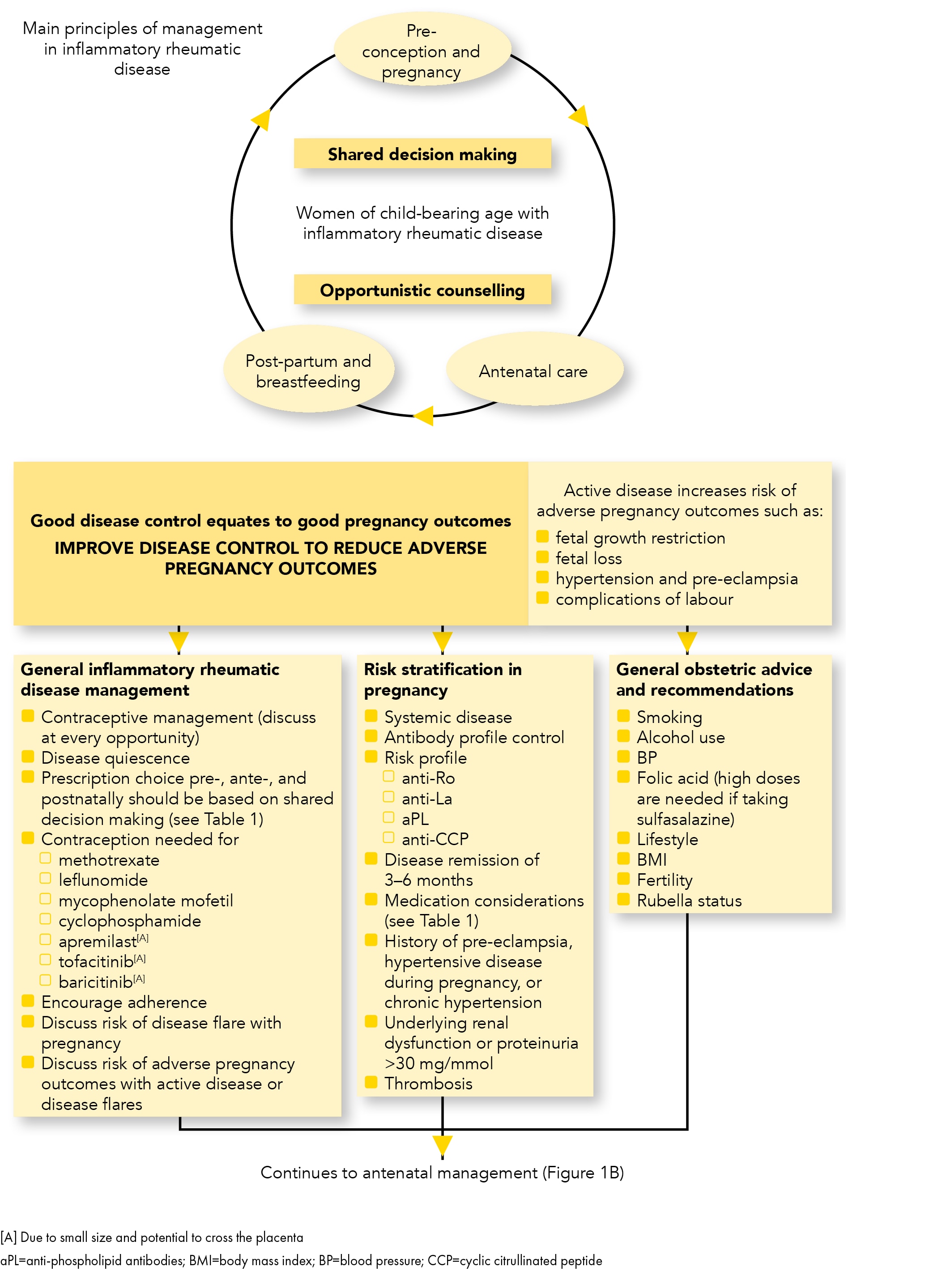

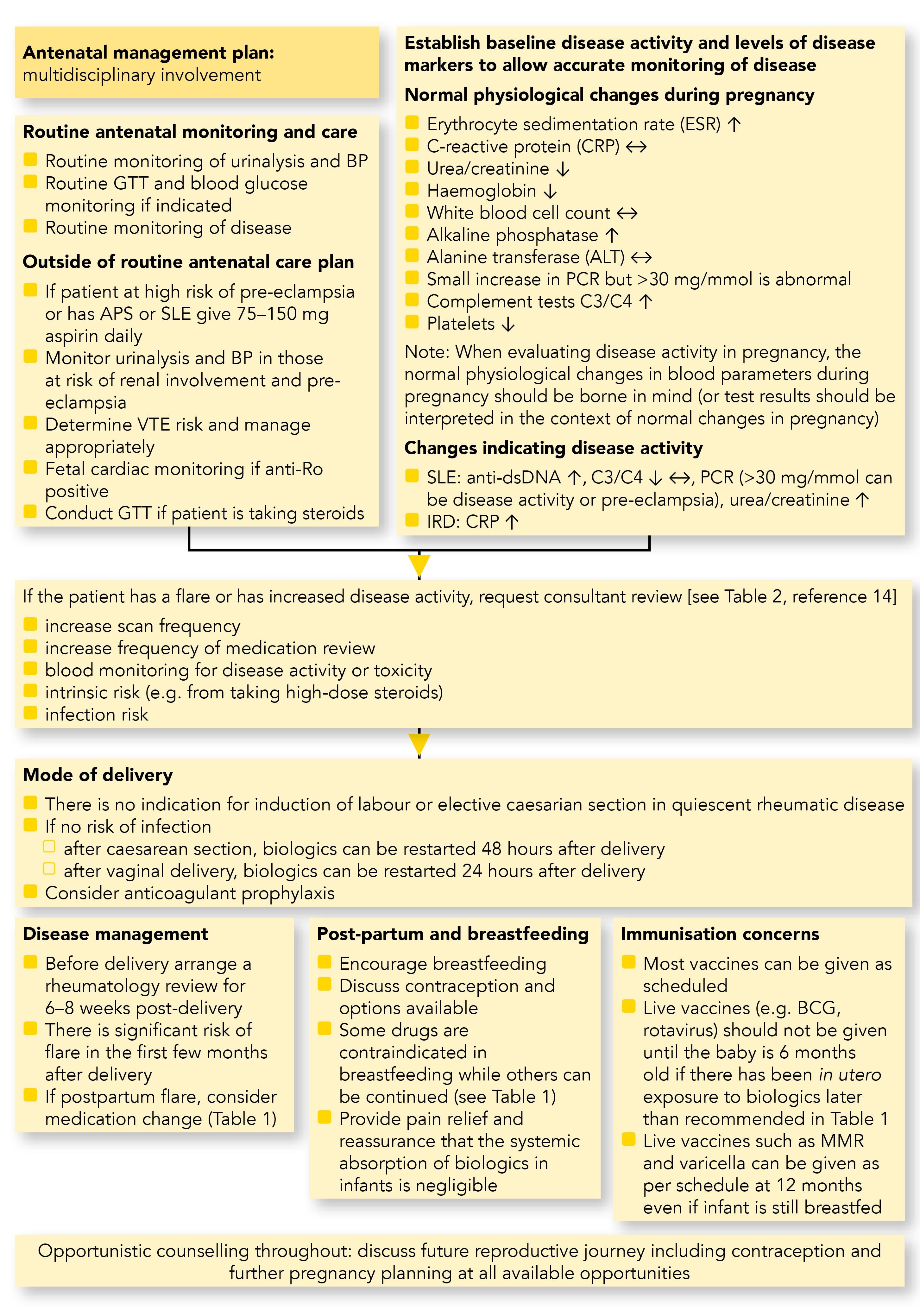

This article sets out the reasons for the guideline and some important aspects of the guidance. The algorithm in Figure 114 summarises the treatment pathway for women of child-bearing potential who have IRD.

Note: At the time of publication (November 2020), some of the drugs discussed in this article did not have UK marketing authorisation for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding for the indications discussed. Prescribers should refer to the individual summaries of product characteristics for further information and recommendations regarding the use of pharmacological therapies. For off-licence use of medicines, the prescriber should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for the decision.5–11 Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information.15

PL=anti-phospholipid antibodies; BMI=body mass index; BP=blood pressure; CCP=cyclic citrullinated peptide

Giles I, Allen R, Nelson-Piercy C et al. Best practice management of women of child-bearing age with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Guidelines, 2020.

APS=anti-phospholipid syndrome; BCG=Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine; BP=blood pressure; CRP=C-reactive protein; dsDNA=double-stranded DNA; GTT=glucose tolerance test; MMR=measles, mumps, and rubella; PCR=protein creatinine ratio; RA=rheumatoid arthritis; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus; VTE=venous thromboembolism

Giles I, Allen R, Nelson-Piercy C et al. Best practice management of women of child-bearing age with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Guidelines, 2020.

Holistic Management

Good communication ensures women of child-bearing age are aware of the options available to them. All healthcare professionals should be prepared to question patients with IRD about their contraceptive needs to avoid unplanned pregnancy, particularly if the patient is taking pregnancy-incompatible medication. For women considering pregnancy, counselling is necessary to obtain information on the disease and any systemic involvement to allow risk stratification of care during pregnancy. Patients should conceive when their disease is inactive, generally 3–6 months post disease flare, to avoid an increased risk of flare during pregnancy.1,7 Pregnancy compatible drugs should be prescribed1,2,5–11,16,17 when a patient is considering (or has already achieved) pregnancy to reduce the risk to them and their baby from uncontrolled inflammation. It is important to improve the patient’s understanding of the importance of pregnancy planning and adherence to medication.1,2

Any discussion about treatment choice with women of reproductive age should include questions about whether the patient is considering pregnancy, and the timing of potential pregnancy, as that could preclude the use of some drugs. Drugs that are contraindicated for pregnancy should only be prescribed with or after appropriate contraceptive advice has been given.

Contraception and Unplanned Pregnancy

Contraceptive management is important for women with IRDs due to the potential risks of an unplanned pregnancy during active disease and/or the risks of the use of teratogenic drugs to mother and baby.7,11 Certain DMARDs should not be given unless appropriate contraception is being used, because of the possible risk of congenital abnormalities in the baby (see Box 1).14 The choice of contraceptive should depend on clinical factors (diagnosis and activity of systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], thrombotic risk including the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) and proteinuria, osteoporosis risk, drug–drug interactions), the woman’s needs, and the risk of unplanned pregnancy if contraception fails.11 In cases of unplanned pregnancy, urgent advice from specialists with relevant experience must be sought to determine the risk to the unborn child from any contraindicated drugs.

| Box 1: Treatments Requiring Appropriate Contraceptive Advice14 |

|---|

When prescribing or re-issuing the following drugs commonly prescribed in inflammatory rheumatic disease, it is imperative that the patient receives appropriate contraceptive advice due to a varying level of risk of these drugs to the unborn child:

Note A: Non-TNFi biologic medications have limited documentation on safe use in pregnancy and should only be considered in consultation with specialist advice if no other pregnancy compatible drug is available. TNFi=tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors Giles I, Allen R, Nelson-Piercy C et al. Best practice management of women of child-bearing age with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Guidelines, 2020. |

Pre-pregnancy Counselling

All women should have access to pre-pregnancy advice from specialist rheumatology services and/or obstetric/fetal medicine services according to the complexity of issues. Multiple opportunities for pre-pregnancy (or contraceptive) counselling exist:

- at diagnosis

- during routine consultations

- at treatment initiation and changes

- when issuing repeat prescriptions for contraception

- during annual review

- when initiated by the patient.

The best use of medicines in pregnancy (BUMPS) website18 should be consulted before any new treatment is initiated, to ensure appropriate advice about contraception is given if pregnancy is contraindicated (see Box 1). Any pre-pregnancy counselling session should explain that disease control can improve fertility and reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, to engage the woman in her care and to increase her adherence with medication.

Reassurance can be given regarding the very low risk of a child inheriting inflammatory rheumatic disease from a parent as these are polygenic diseases with a variety of environmental influences and genes implicated in the pathology.19 Folic acid is recommended in any pregnancy but high doses (5 mg/day) should be given to women taking sulfasalazine as well as to women who are diabetic, obese, and/or who have a history of a neural tube defect in themselves or in a previous pregnancy, and to those who accidentally conceive on methotrexate.5,14

Other topics to discuss include disease-specific questions, evaluation of auto-antibody profile (for anti-Ro/La antibodies and/or aPL antibodies), risk of VTE, presence of underlying renal dysfunction or proteinuria and increased risk of pre-eclampsia.20 Women with a previous history of pre-eclampsia, hypertensive disease during pregnancy, or chronic hypertension, require monitoring in pregnancy and their hypertension managed as per NICE guidance.20 The ability, and support available, to care for the baby after the birth should also be considered, especially if the new mother experiences a post-partum flare. Furthermore, reassurance should be given that rarely is vaginal birth contraindicated or caesarean section indicated for maternal rheumatic disease (as opposed to obstetric reasons).

Autoantibody Profile and Thrombotic Risk

Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB autoantibodies can be present in patients with SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome, and occasionally in women with other IRDs. Women with such conditions should be screened for these antibodies before pregnancy as they are associated with an increased risk of neonatal lupus. Congenital complete heart block occurs in 1–2% of babies born to mothers with these antibodies.1,11 Babies with potential heart block due to the anti-Ro and/or anti-La status of the mother should be identified in utero using fetal heart rate monitoring from 16 weeks gestation.11 If heart block is identified, the baby must be assessed by a fetal cardiologist for signs of other cardiac abnormalities and delivery can be planned via elective caesarean section because there is a risk that fetal bradycardia resulting from complete heart block may mask signs of fetal distress during delivery. Women with these antibodies who have experienced neonatal lupus in previous pregnancies and are treated with hydroxychloroquine before and during pregnancy have a reduced risk of complete heart block in a subsequent pregnancy.11,21 Complete heart block usually requires treatment with a pacemaker, either soon after the baby has been born or during childhood, and ongoing monitoring of the child is required.

The three different types of aPL include lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin, and anti-β2 glycoprotein 1, and can all increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and maternal thrombosis. The level of risk depends on the number and type of aPL and increases with:1,9

- triple positivity in all three tests

- lupus anticoagulant positivity, and/or

- persistent high antibody titre on repeated measurements.

A repeat test is needed to demonstrate persistence and the patient should be followed according to the 2019 guidance from the European League Against Rheumatism.9

Women of child-bearing age who have active inflammatory disease are at increased risk of developing VTE during pregnancy.22 Women at high risk should be offered a management plan that provides thromboprophylaxis, usually with low molecular weight heparin, based on the woman’s individual risk.1 Appropriate treatment guidance such as the Green-top guideline from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) identifies risk based on patient-specific factors such as previous recurrent VTE, family history of VTE, age, obesity, current systemic infection, disease activity, and severe proteinuria.23 Heparin treatment should be continued post-partum to minimise the thrombotic risk.23

Prescribing Considerations During Pregnancy

Table 114 shows which DMARDs and corticosteroids can be used pre-pregnancy, during pregnancy, and when breastfeeding, with considerations about timing and other aspects of treatment.5,8,11,16,17

Table 1: Drug Compatibility with Pre-conception, Pregnancy, and Breastfeeding1

| DrugA | Pre-conception | During Pregnancy | Breastfeeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | |||

| Prednisolone (oral) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IV methylprednisolone | Reserve for flares | Reserve for flares | Reserve for flares |

| Antimalarials | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MepacrineB | No | No | No |

| DMARDs | |||

| Azathioprine | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ciclosporin | Yes | YesC | YesD |

| Cyclophosphamide | No | No | No |

| Intravenous immunoglobulins | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Leflunomide | No; cholestyramine washout | No | No |

| Methotrexate | Stop 3 months in advance | No | No |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Stop 6 weeks in advance | No | No |

| Sulfasalazine (with 5 mg folic acid) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tacrolimus | Yes | YesC | YesD |

| TNFi Biologics | |||

| Adalimumab | Yes | Maintain pregnancy dosing until third trimester and resume post-partum | CautionD |

| Certolizumab | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Etanercept | Yes | Maintain pregnancy dosing until third trimester and resume post-partum | CautionD |

| Golimumab | Yes | Maintain pregnancy dosing until third trimester and resume post-partum | CautionD |

| Infliximab | Yes | Maintain pregnancy dosing, stop in second trimester and resume post-partum | CautionD |

| Non-TNFi Biologics | |||

| Anakinra | Yes | Limited but reassuring data on use in systemic autoinflammatory diseases in pregnancy24 | CautionD |

| Rituximab | Stop 6 months pre-conception. Due to limited documentation on use in pregnancy, only consider using after specialist advice if no other pregnancy compatible drug available. | CautionD | |

Abatacept Belimumab Secukinumab Tocilizumab Ustekinumab | Discontinue in first trimester. Due to limited documentation on use in pregnancy, only consider use later in pregnancy after consultation with specialist advice if no other pregnancy compatible drug is available. | CautionD | |

| Small Molecules | |||

Apremilast Baricitinib Tofacitinib | Stop 1 month before conception1 | Not recommended due to lack of data; potential ability of small molecules to cross the placenta and into breast milk | |

Note A: At the time of publication, some of these drugs did not have UK marketing authorisation for use in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Prescribers should refer to the individual SmPCs for further information regarding the use of pharmacological therapies. For off-licence use of medicines, prescribers should follow relevant professional guidance,5–11,16,17 taking full responsibility for the decision. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information.15 | |||

It is important to discuss continuation and duration of treatment, particularly biologics, based on the patient and their disease features, other therapeutic options, and the characteristics of the specific biologic they have been prescribed.1,11 Certolizumab does not cross the placenta at significant levels as it does not have an Fc component necessary for transport into the fetal circulation.1,11 Infants may have an increased risk of infection if certain biologic therapies that can cross the placenta are administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy (see Table 1)14 and persist in the neonatal and infant’s circulation. Therefore, live vaccines, such as Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine (BCG) or rotavirus, should not be administered to infants that have been exposed to these drugs during pregnancy until the infant is 6 months of age (see Box 2).1 Regarding biosimilars, no differences are expected in safety and efficacy when compared with the reference medicine.25

| Box 2: Immunisation in Infants Born to Women who are Being Treated for Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease14 |

|---|

BCG=Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine; MMR=measles, mumps, and rubella |

Prednisolone may be used to treat disease flares during pregnancy. There is an increased risk of complications (including infection) with continued use of high-dose (>20 mg) prednisolone.26 It is important to titrate to the minimum tolerable prednisolone dose (ideally <10 mg) with optimal dosing of non-steroid immunosuppressants and regular screening for hypertension and gestational diabetes plus optimisation of vitamin D levels. All patients should be monitored for adverse pregnancy outcomes in addition to disease flare, regardless of whether their disease is stable or active, and management should be stratified according to risk and presence of organ involvement. Women with underlying renal dysfunction or proteinuria >30 mg/mmol have an increased risk of pre-eclampsia and should be offered low-dose aspirin during pregnancy; hypertension should be managed in accordance with NICE guidance.20 Routine obstetric monitoring should be consultant-led and rheumatology review is required in patients with active or previously severe disease and in those requiring changes in therapy.

Prescribing Considerations Post-partum

If there is concern about disease control, biologic treatment can be resumed no earlier than 24 hours after a vaginal delivery or 48 hours after a caesarean section, in the absence of infection.16 Contraception needs post-partum should be discussed prior to delivery and at post-partum assessment. A post-partum appointment should be scheduled in advance of the birth and planned for 6–8 weeks after delivery to evaluate disease activity, to assess if any dose changes are needed, and to provide contraception advice.

After birth, breastfeeding should be encouraged with compatible drug use (see Table 1).14 Advice regarding vaccinations (see Box 2)14 should be followed to protect the infant against infectious diseases. If the patient has had a disease flare during pregnancy, they should be reassessed for all thrombotic risk factors to see if they require antithrombotic therapy post-partum.

Summary

Practitioners managing women with inflammatory rheumatic diseases in the reproductive age range should ensure that they discuss plans for pregnancy regularly. It is important that women are aware of the importance of good disease control on appropriate treatment before, during and after pregnancy to ensure optimal outcomes for mother and baby. Drugs that are known to cause possible harm to a fetus should not be prescribed without adequate discussion about contraception. Patients should receive pre-pregnancy counselling so that they are aware of the possible risks associated with their disease and its treatment and how these risks can be minimised.

Professor Ian Giles

Professor of Rheumatology, Centre for Rheumatology Research, University College London

Professor Caroline Gordon

Emeritus Professor of Rheumatology, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; IRDs=inflammatory rheumatic diseases |