Sarah Leyland, Virginia Wakefield, and Dr Zoe Paskins Highlight Six Essential Points from the Royal Osteoporosis Society Guidance on Physical Activity and Exercise for People with Osteoporosis

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article    |

Osteoporosis is a common bone disease characterised by a micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue. This deterioration increases the risk of fracture in situations where the mechanical forces involved would not ordinarily result in fracture (also known as fragility fracture), such as a fall from standing height or less. Diagnosis of osteoporosis is based upon a low bone mineral density (BMD) in the osteoporosis range measured using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS), in the context of the new consensus statement discussed in this article, also considers patients with a significant fracture risk (based on a fracture risk assessment) with or without fragility fractures as having osteoporosis.1

Reduced bone density is a major risk factor for fragility fractures, which most often occur in the spine, hip, or wrist. One in two women and one in five men aged over 50 years are expected to break a bone during their lifetime as a result of osteoporosis.2 A recent report of six EU countries, including the UK, found the fragility fracture burden (measured in disability-adjusted life years) to be greater than for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and ischaemic stroke, and surpassed only by ischaemic heart disease, dementia, and lung cancer.3

To improve outcomes related to osteoporosis, practitioners need to manage fracture-related symptoms and help prevent further fractures. Prevention is achieved by identifying people at risk, conducting timely fracture risk assessments (including referral for bone density measurement where appropriate), treatment with drug therapies, monitoring treatment adherence, and referring to secondary care if necessary.

Source: Professor Alan Boyde, 2015

Supporting patients also involves providing information to help them self-manage their condition through lifestyle changes, including exercise and physical activity. It is widely understood that physical activity and exercise help to make bones strong; however, patients report that they are given insufficient information about non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis and receive conflicting and confusing messages from healthcare professionals, particularly around exercise.4

In 2018, the Royal Osteoporosis Society (formerly the National Osteoporosis Society) convened an expert group of clinicians, scientists, and practitioners from around the UK to:

- clarify the role of exercise in increasing bone strength and reducing risk of falls and fracture

- examine the role of exercise and physical activity to address pain and symptoms of vertebral fractures

- agree consistent advice on the safety of exercise for people with osteoporosis.

A consensus statement1 was published in December 2018 providing detailed recommendations for people with osteoporosis. The recommendations augment existing UK Chief Medical Officers’ guidelines on exercise for the general population (at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week and exercise to help with strength and balance on at least 2 days a week)5 providing specific detail as to the type and level of exercise and physical activity that will promote bone strength.

This article highlights the key principles underpinning the new recommendations, and a breakdown of the three key areas of physical activity and exercise:

- strong—exercise to promote bone strength

- steady—exercise to reduce falls and resulting fractures

- straight—exercise that focuses on spine care, and a positive approach to bending, lifting, and moving safely.

1. Think Strong, Steady, and Straight

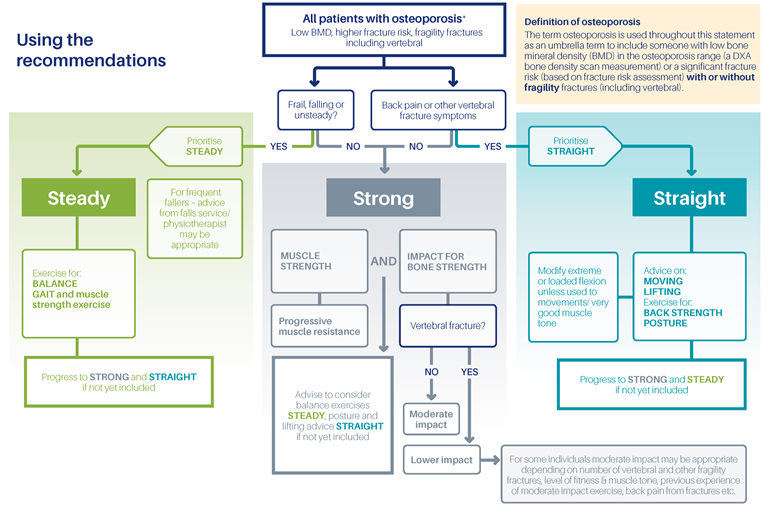

When assessing a patient with osteoporosis, all three key areas should be considered. Typically, one or more areas will be a priority according to the patient’s individual needs. Healthcare professionals can encourage patients who are otherwise fit to prioritise ‘strong’, while frail or falling patients should start with ‘steady’ before progressing to bone strength (strong) exercises. Patients who have back pain or other vertebral fracture symptoms should focus on the recommendations under ‘straight’, before considering the other areas. Practitioners can refer to the Strong, Steady, and Straight quick guide for a flow-chart to guide how to choose which exercise type is most appropriate for the patient (see Figure 1).1

A practical suite of materials, including factsheets and video clips for patients, is available from the ROS website.

Source: Royal Osteoporosis Society. Strong, steady and straight. ROS, 2018. Available at: theros.org.uk/forms/documents/strong-steady-and-straight

Reproduced with permission

2. Encourage People with Osteoporosis to Do More Exercise

People with osteoporosis should be encouraged to do more rather than less exercise following their diagnosis. Healthcare professionals need to adopt a positive and encouraging approach focusing on ‘how to’ messages rather than ‘don’t do’. Although specific (and relatively high) levels of activity may be most effective to promote bone strength, even a minimal increase in activity should be encouraged as it may provide some benefit. Inactivity must be discouraged as it results in a decline in bone density.1

3. Advise Patients That There is Little Evidence of Harm Associated with Exercise

The expert group examined all the evidence of harms associated with exercise for people with osteoporosis. The evidence indicates that physical activity and exercise is not associated with significant harm, including vertebral fractures. In general, the benefits of exercise outweigh the risks. Healthcare professionals should acknowledge patients’ understandable fear of exercise causing injury, while supporting them to understand that this is not backed up by the evidence.1

4. Strong—Know Which Exercises Promote Bone Strength

Ideally, a combination of weight-bearing exercise involving impact, and muscle strengthening exercise is recommended to promote bone strength. Both types of exercise may provide some benefit alone, but they are most effective when combined.1

Weight-bearing Exercise Involving Impact

Provided a patient does not have a vertebral fracture or multiple fragility fractures, they should be advised to exercise up to a ‘moderate’ impact level. This includes:

- racquet sports

- running or jogging

- jumping/hopping

- dancing

- track events.

Patients with vertebral fractures or multiple fragility fractures should start exercising at low impact levels (e.g. Nordic walking, stair climbing, marching, walking, side steps), increasing to moderate levels depending on factors such as number of fractures and whether back pain has resolved. No recommendations are made about higher-impact exercise (e.g. exertional jumps such as high vertical jumps, star jumps) as there is no evidence that this type of exercise is beneficial or safe for people with osteoporosis. All patients should build up their levels of physical activity and exercise slowly, taking into account their ability and experience.1

Healthcare professionals can encourage patients towards activities that meet these criteria. Exercises such as swimming and cycling, while important for muscle strengthening (see below) and cardiovascular health, are not weight-bearing and do not involve impact. They will not therefore deliver optimum benefit in terms of bone strength. Adopting new exercise habits may be difficult for some patients. Healthcare professionals can help patients to think creatively around their preferred activities. For example, if a patient enjoys swimming, jogging 25 paces to and from their car to the swimming pool will incorporate the necessary impact required (the target is at least 50 impacts per session) to promote bone health.1

Muscle Strengthening Exercise

Alongside impact exercises, muscle strengthening exercises are important to maximise improvements to bone strength. Progressive muscle resistance training is one of the most effective means of achieving this, and involves a gradual increase in resistance or weight over time, exercising to muscle fatigue. Patients should be encouraged to seek out supervision from an exercise professional initially to ensure good technique. For patients who are averse to dedicated weight training exercise, other muscle building activities include sports such as rowing, and day-to-day activities such as aerobics, Pilates, gardening, and carrying shopping.1

5. Steady—Recommend Challenging Balance Exercises

Fear of falling and/or co-morbidities that limit mobility can lead to a vicious spiral of inactivity. Before embarking on an exercise routine to improve bone health, patients with osteoporosis who are at risk of falls should be encouraged to do exercises, two to three times per week, that help improve their balance and coordination. Any activity that causes a ‘wobble’ or feeling of unsteadiness is likely to promote balance and core strength. Evidence suggests that the Otago exercise programme and the Falls Management Exercise (FaME) programme are beneficial for patients who have already experienced falls. Tai chi, yoga, and Pilates are recommended for all people with osteoporosis, particularly those with balance problems. Interventions that do not challenge balance sufficiently (e.g. seated exercise programmes) are not recommended.1

It is important that healthcare practitioners consider the way in which they communicate the benefits of falls prevention exercise to patients. Most people with osteoporosis do not perceive themselves as ‘fallers’ or as frail. People are more motivated to do balance exercises when practitioners use terms like ‘maintaining independence’ and ‘reducing the risk of fractures’ rather than ‘fall prevention’. It can also be helpful to emphasise the importance of balance in feeling confident and able to take part in the activities that the patient enjoys doing.

6. Straight—Promote Caring for the Spine and Strengthening Back Muscles

Exercises that focus on caring for the spine and strengthening back muscles enable safe movement, improve posture, and provide pain relief for vertebral fractures.

After a diagnosis, many people with osteoporosis fear the movement involved in everyday living. They may have heard that stretching, bending, lifting or twisting could cause a vertebral fracture. It is important that patients receive prompt advice on how to move safely. Healthcare professionals can provide information on how to amend posture and everyday movements to keep the upper back straight— including safe lifting techniques, the ‘hip hinge’, and moving in a controlled and smooth way. Royal Osteoporosis Society materials for patients are available on the ROS website, and the ROS Helpline on 0808 800 0035, which is staffed by experienced osteoporosis nurses, can provide further information and support.1

People with painful vertebral fractures need clear and prompt guidance on how to use muscle building exercises to help with posture and pain. Daily exercises to strengthen back muscles, at low intensity and focusing on endurance, are recommended. Referral to a physiotherapist for tailored advice may be appropriate but should not preclude useful advice as soon as fractures occur. As well as individual back exercises, other activities that can be beneficial include yoga, Pilates, and hydrotherapy, with the proviso that movements involving sustained, repeated, or end-range forward flexion (e.g. bending to touch toes) are to be avoided unless the patient is experienced and comfortable with these activities.1

Conclusion

Primary care practitioners are well placed to empower patients to manage their condition with a positive mindset.

When a patient presents with osteoporosis and/or fragility fractures, healthcare professionals can now encourage them to consider exercise in line with new evidence-based recommendations from the ROS, and signpost them to the charity’s resources at theros.org.uk/exercise. Practitioners can:

- explain to patients that harm from exercise is unlikely and support them to choose activities that will promote bone strength—this involves exercises involving impact and muscle strengthening

- explain the importance of avoiding falls by means of a challenging balance activity

- acknowledge the fear of fracture commonly felt by people with osteoporosis and address it with prompt information on safe movements and posture (and referral to physiotherapy).

Sarah Leyland

Nurse Consultant, Royal Osteoporosis Society

Virginia Wakefield

Project Officer, Royal Osteoporosis Society

Dr Zoe Paskins

Senior Lecturer and Honorary Consultant in Rheumatology, Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, Keele University

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

|