Dr Caroline Rayment Discusses how the New NICE Guideline will Help Practitioners Provide Early and Consistent Treatment to Patients with Suspected Lyme Disease

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find Key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of the article. |

Lyme disease is an infection caused by a number of bacteria belonging to the Borrelia genus, including Borrelia burgdorferi. Borrelia are spirochetes, and have many similarities to the syphilis organism. Lyme disease is transferred to humans by the bite of an infected tick (not all ticks carry Lyme disease). There appears to be a wide variation in prevalence of bacteria within tick populations although there is limited epidemiological data to verify this.

The incidence of Lyme disease is on the rise. Data from Public Health England show that there were 1534 confirmed cases of Lyme disease in England in 2017, compared with 1134 cases in 2016.1 There is, however, likely to be significant under-reporting owing to a combination of factors. Estimates for the UK are based on confirmed laboratory cases from NHS testing sites—notably the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory at Porton Down in England and the National Lyme Borreliosis testing laboratory in Scotland. Therefore, these estimates do not include diagnoses made on purely clinical presentation or diagnoses that have been missed. Lyme disease is not a notifiable disease in the UK.

Why Was a Guideline Needed?

Lyme disease can be a multisystem infection. Early on in the disease process it may just present with a simple skin rash, but there has been much discussion about the long-term sequalae for people with Lyme disease, which can involve several organ systems. It has also been considered hard to diagnose, with many patients believing they have had untreated Lyme disease for years because laboratory tests only identify antibody response, not an active infection. This has led to a two-tier system where many patients feel that the NHS has left them undiagnosed and poorly treated, while some private practitioners offer high-cost but poorly evidenced services.2 This has been further confused by the wide variation in guidelines between the two main Lyme disease groups in the USA—the Infectious Diseases Society of America3 and International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society4.

In April 2018, NICE published NICE Guideline (NG) 95 on Lyme Disease.5 Before this there were no UK guidelines that covered both primary and secondary care. The guideline is unable to answer all questions on Lyme disease—there is a lack of good quality evidence on epidemiology, prevalence, diagnosis, and management—however, it is a pragmatic guideline with a particular focus on primary care. It aims to improve the diagnosis of Lyme disease at an early stage and ensure prompt and adequate treatment with the correct antibiotic. It aims to increase the awareness of Lyme disease and to highlight where there are still uncertainties, which will hopefully direct future research. The guideline focuses on the diagnosis and management of Lyme disease according to clinical presentation and symptoms rather than using the differing classifications of Lyme disease, which are poorly defined and contested.5

Where Are Ticks Found?

Ticks are found in grassy/wooded areas and so they can be found anywhere in the UK (it is necessary to move away from the often-repeated phrase ‘you can’t get Lyme disease here’) although there are areas of higher prevalence. There is an increased risk of disease in Scotland and the South of England. There are also countries with higher prevalence of Lyme disease, notably the USA, Canada, central and eastern Europe, and Scandinavia.5 Patient groups who may be especially at risk are those who take part in outdoor pursuits, such as gardening, walking, running, or camping. Urban parks can also have a high level of ticks. Occupational groups may also be affected, such as farmers or forestry workers. General Practitioners should take an approach of ‘where have you been and what have you been doing?’ when Lyme disease is suspected.

Removing a Tick

It is best to remove a tick while it is still alive, with a specialised tick remover or fine-tipped tweezers. It is important not to kill the tick when it is attached as this can increase the risk of transmission.6 It is wise to clean the area with antiseptic or soap and water and to keep an eye on it for any subsequent skin changes. Many tick bites are unnoticed as they tend to be painless and are often found in the hairline, groin, or axillae. The NG95 committee found no evidence to support the use of prophylactic treatment following a tick bite.

How to Diagnose

The most common presentation of Lyme disease is an erythema migrans (see Figures 1–3)—this is pathognomonic and therefore no other tests are needed. The erythema migrans rash is different from the inflammatory reaction that can occur with any insect (which tends to come up within the first 24 hours, be intensely itchy and hot, and may subside relatively quickly) and presents as a rash that is:5

- red, increases in size, and may sometimes have a central clearing; however, it may not always have the classic ‘bulls eye’ appearance

- not usually itchy, hot, or painful

- usually visible from 1–4 weeks (but can appear from 3 days to 3 months) after a tick bite and lasts for several weeks

- usually at the site of a tick bite—there may be multiple rashes.

2.jpg)

Source: CDC

.jpg)

Source: PCDS www.pcds.org.uk

Source: PCDS www.pcds.org.uk

If the classic initial skin presentation of erythema migrans is missed, or is not present (Public Health England reports that about one-third of patients in the UK do not present with a rash7), then diagnostic uncertainties can arise as many of the other symptoms of Lyme disease have a huge overlap with other diseases.

Lyme disease should be considered in people presenting with symptoms and signs relating to one or more organ systems (focal symptoms) because Lyme disease is a possible but uncommon cause of:5

- neurological symptoms:

- facial palsy or other unexplained cranial nerve palsies

- meningitis

- mononeuritis multiplex or other unexplained radiculopathy

- (rarely) encephalitis, neuropsychiatric presentations, or unexplained white matter changes on brain imaging

- inflammatory arthritis affecting one or more joints that may be fluctuating and migratory

- cardiac problems (e.g. heart block or pericarditis)

- eye symptoms (e.g. uveitis or keratitis)

- other skin rashes, including acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans or lymphocytoma

Consider the possibility of Lyme disease in people presenting with several of the following symptoms, because Lyme disease is a possible but uncommon cause of:5

- fever and sweats

- swollen glands

- malaise

- fatigue

- neck pain or stiffness

- migratory joint or muscle aches and pain

- cognitive impairment, such as memory problems and difficulty concentrating (sometimes described as ‘brain fog’)

- headache

- paraesthesia.

Investigations

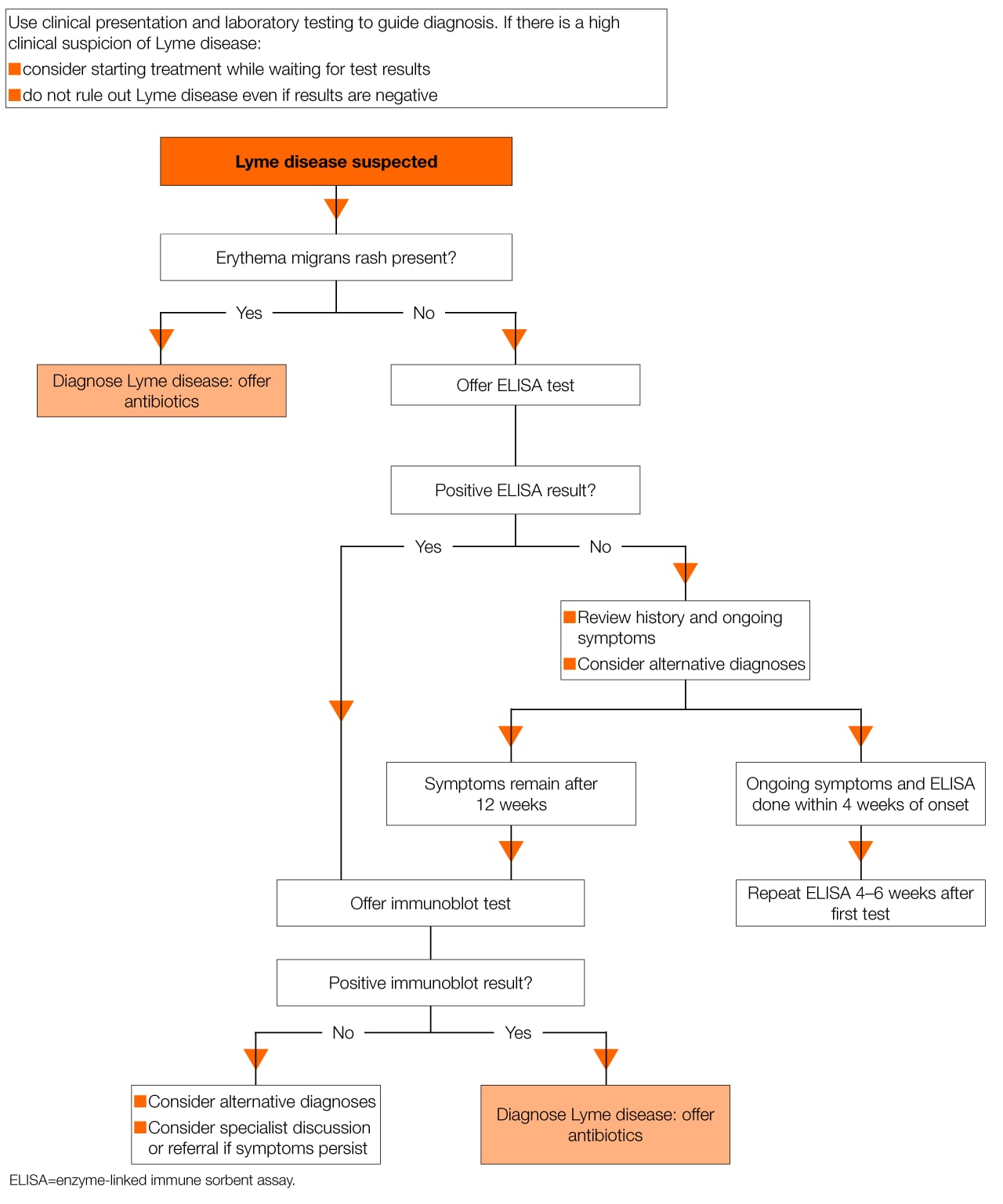

Lyme disease is essentially a clinical diagnosis, but serological tests can be used to detect antibodies to the Borrelia bacteria, which may act as confirmation. This forms a two-tier testing system where a sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test is performed first, followed by a confirmatory immunoblot test for positive or equivocal results. A treatment algorithm from NICE (see Figure 4) may be helpful.5

Particular diagnostic conundrums may occur because tests for Lyme disease are not 100% sensitive or specific and should only be performed to support clinical observations. Antibody tests may be performed too early when a response will not yet be positive, so these may need to be repeated 4–6 weeks later. Test results may also be falsely negative if there is a reduced immune response—e.g. if the patient is taking immunosuppressant medication. Do not make a diagnosis of Lyme disease with a positive test result but no clinical symptoms.5 The seroprevalence of Lyme disease is currently unknown. There is no test to assess for active infection and no ‘test of cure’.5

Management and Referral

If Lyme disease is suspected, GPs should refer all children under the age of 12 years unless they are being treated for a single erythema migrans lesion and have no other symptoms. It is also advisable to seek secondary care advice for patients who have had two separate courses of antibiotics and are still symptomatic, and for those whose clinical picture fits the diagnosis of Lyme disease but who test negative.5

It is sensible to review the diagnosis of Lyme disease in patients who do not seem to be responding to treatment.5

Be aware that some symptoms—especially neurological symptoms—may persist after successful treatment due to damage caused by the organism.

Table 1 shows antibiotic treatments recommended by NICE5 for adults and young people aged over 12 years. Table 2 shows antibiotic treatments recommended by NICE5 for children aged under of 12 years.5 This information is also available in the form of a useful algorithm. Doses and duration of antibiotic treatment have been chosen at the higher ranges of formulary doses and lengths of treatment to avoid the possibility of under-treatment. There was a lack of evidence to support extended courses of antibiotics for people with persisting symptoms.8

What Next for Lyme Disease Patients?

Five comprehensive research recommendations are made by the committee of NG95 at the end of the guideline.5 At first glance these seem quite overwhelming but in the author’s opinion, they are a reflection of the lack of reproducible evidence that is available to guide clinicians. A Danish study published in May 2018 on the long-term outcomes for European Lyme neuroborreliosis offers reassurance to patients.9 GPs can assure patients with a confirmed microbiological diagnosis of neurological symptoms of Lyme disease that this will have no effect on their survival, wellbeing, or social parameters 10 years after diagnosis compared with a control population.2

Lyme disease has always been an illness that, in the author’s opinion, healthcare practitioners have been very cautious about diagnosing. It has not been very common in the UK and the controversy worldwide about best treatment methods has left patients feeling that they have not been listened to and have therefore had to seek alternative private, expensive, and poorly evidenced treatment. It is unhelpful that there is no test for active infection, which leads clinicians to doubt the diagnosis and in turn contributes to more uncertainty for the patient.

The main change that will happen as a result of NG95 is that there will be one clear pathway for suspected Lyme disease in England. It is hoped that the guideline will raise the awareness of GPs to the prevalence of Lyme disease throughout the UK, the range of symptoms that should cause suspicion, and the serious manifestations that should not be missed. The guideline committee chose to simplify the treatment algorithms so that there is less room for error, and the committee’s expert view was that the dose of some of the antibiotics should be increased in line with other infectious diseases of similar severity.

The NICE guideline was therefore timely and will hopefully spark further research into this complex illness. The fact that the RCGP has chosen Lyme disease as a spotlight project for 2018/19 can only advance the understanding of medical practitioners and the wider engagement of the public.

Dr Caroline Rayment

GP, Burley in Wharfedale

Member of the guideline development group for NG95

| Key Points |

|---|

|

| Implementation actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system |