Professor Anton Emmanuel Offers Six Top Tips on Managing Constipation in Primary Care

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

|

At least one in 10 people in the UK experiences a bowel problem;1 despite this, many patients are hesitant about discussing such issues. When it comes to constipation, there is an assumption that it is not a serious condition (see Box 1),2 and this means that patients may wait too long before seeking treatment. In 2018–2019, 76,929 people were admitted to hospital with constipation in England—equating to almost 211 people a day. Of these, around three-quarters were unplanned emergency admissions.3

| Box 1: Patients Seeking Advice on Constipation2 |

|---|

In a YouGov survey:

|

There is an urgent need to reduce the rate of hospitalisation for constipation; the figures are rising every year, with the data for 2018–2019 representing an increase of 16% in admissions compared with 2014–2015, and 7.7% compared with 2017–2018.3 This represents a significant burden on the NHS—in 2018–2019, the total cost to hospitals for treating unplanned admissions due to constipation was around £81 million.3 The total sum is likely to be much higher when including GP visits, home visits, and prescriptions.3 A primary care survey conducted in June 2019 suggested that, on average, GPs, nurses, and other healthcare professionals see 6.3 patients with constipation a week.4

Because the NHS must now also cope with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing avoidable costs such as those related to constipation is more critical than ever.

1. Check Whether Constipation is Acute or Chronic

When reviewing patient history and causes, it is important to establish whether the constipation is acute or chronic. Box 2 summarises the criteria that should prompt suspicion of constipation.5

| Box 2: When to Suspect Constipation5 |

|---|

© NICE 2020. Constipation: when should I suspect constipation? Available from cks.nice.org.uk/topics/constipation/diagnosis/diagnosis/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Most patients have ‘functional’ constipation—constipation symptoms with no underlying non-bowel problems.3 If chronic, they may have slow transit constipation, in which case patients may need long-term laxatives (see Box 3).6 However, be aware that constipation may also be a feature of systemic or other intestinal conditions.6

| Box 3: Treatment Summary for Chronic Constipation6 |

|---|

In the management of chronic constipation, treatment should be started with a bulk-forming laxative, whilst ensuring good hydration. If stools remain hard, add or change to an osmotic laxative such as a macrogol. Lactulose is an alternative if macrogols are not effective, or not tolerated. If the response is inadequate, a stimulant laxative can be added. The dose of laxative should be adjusted gradually to produce one or two soft, formed stools per day. If at least two laxatives (from different classes) have been tried at the highest tolerated recommended doses for at least 6 months, the use of prucalopride (in women only) should be considered. If treatment with prucalopride is not effective after 4 weeks, the patient should be re-examined and the benefit of continuing treatment reconsidered. Laxatives can be slowly withdrawn when regular bowel movements occur without difficulty, according to the frequency and consistency of the stools. If a combination of laxatives has been used, reduce and stop one laxative at a time; if possible, the stimulant laxative should be reduced first. However, it may be necessary to also adjust the dose of the osmotic laxative to compensate. British National Formulary. Constipation. Available at: bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/constipation.html All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Encourage Patients to Discuss Constipation

The reluctance of patients to discuss bowel issues is a key challenge in primary care. This can only be addressed through proactive measures, raising awareness about symptoms but also pre-empting cases that may occur and acting accordingly.

Many patients will be embarrassed to discuss their symptoms; asking the right questions can help put them at ease and ensure you are able to find out all the necessary details.

2. Review Patient Co-morbidities

Patients with reduced nervous control who have conditions such as spina bifida or Parkinson’s disease often suffer from ‘neurogenic’ constipation.7 Chronic constipation may also be a side-effect of other diseases such as endometriosis, diabetes, and underactive thyroid.8,9 Lastly, there may be a mechanical pelvic cause, so it is important to ask about vaginal or rectal digitation during defaecation.10

Assess Patient’s Medication

Certain drugs can increase the likelihood of constipation (see Box 4), including opiates or antihistamines.8 When prescribing opiates for another condition, especially in elderly or frail individuals or people with cancer, GPs can consider co-prescribing a laxative to pre-empt constipation symptoms.

| Box 4: Drugs that May Cause Secondary Constipation8 |

|---|

NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug © NICE 2020. Constipation: what are the secondary causes? Available from cks.nice.org.uk/topics/constipation/background-information/secondary-causes/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

3. Investigate the Impact of the Patient’s Lifestyle

The increasing prevalence of constipation can partly be attributed to environmental stressors. For example, the busy pace of modern life can make it difficult to respond immediately to the body’s urge to defaecate, and to have a regular, unhurried toilet routine; both of these elements are important for preventing constipation. Additionally, people may not be getting enough exercise because of a sedentary lifestyle.11

Diet

Poor diets, particularly featuring processed foods with a lack of fibre, are a common cause of constipation.11 Insufficient fluid intake is also a factor, and can be easily addressed.11 Older patients and care home residents in particular are at high risk of dehydration, so this could be aggravating their symptoms.12

4. Be Aware of Other Risk Factors

Multiple risk factors can contribute to the development of constipation, including advancing age, co-morbidities, and reduced mobility, as well as social or psychological factors.11 However, improving awareness of symptoms among carers and patients, and proactively discussing symptoms with patients to help overcome their embarrassment, may help to reduce the number of cases.

Constipation is also more common among women and they are twice as likely to have this condition, often as a result of pregnancy or pelvic floor disorders;10,13 60% of constipation-related hospital admissions are recorded as female, although this may be because women tend to be more willing to seek medical support.3,14

5. Consider Treatment Options

It is important to be aware of all the possible treatment options beyond lifestyle changes and laxatives. It is worth checking whether the patient has already taken over-the-counter laxatives, because they may have tried to resolve the problem alone before seeking help. Laxatives are often seen as an easy solution to alleviating constipation, but may not be the right option in light of the other possible causes outlined above.

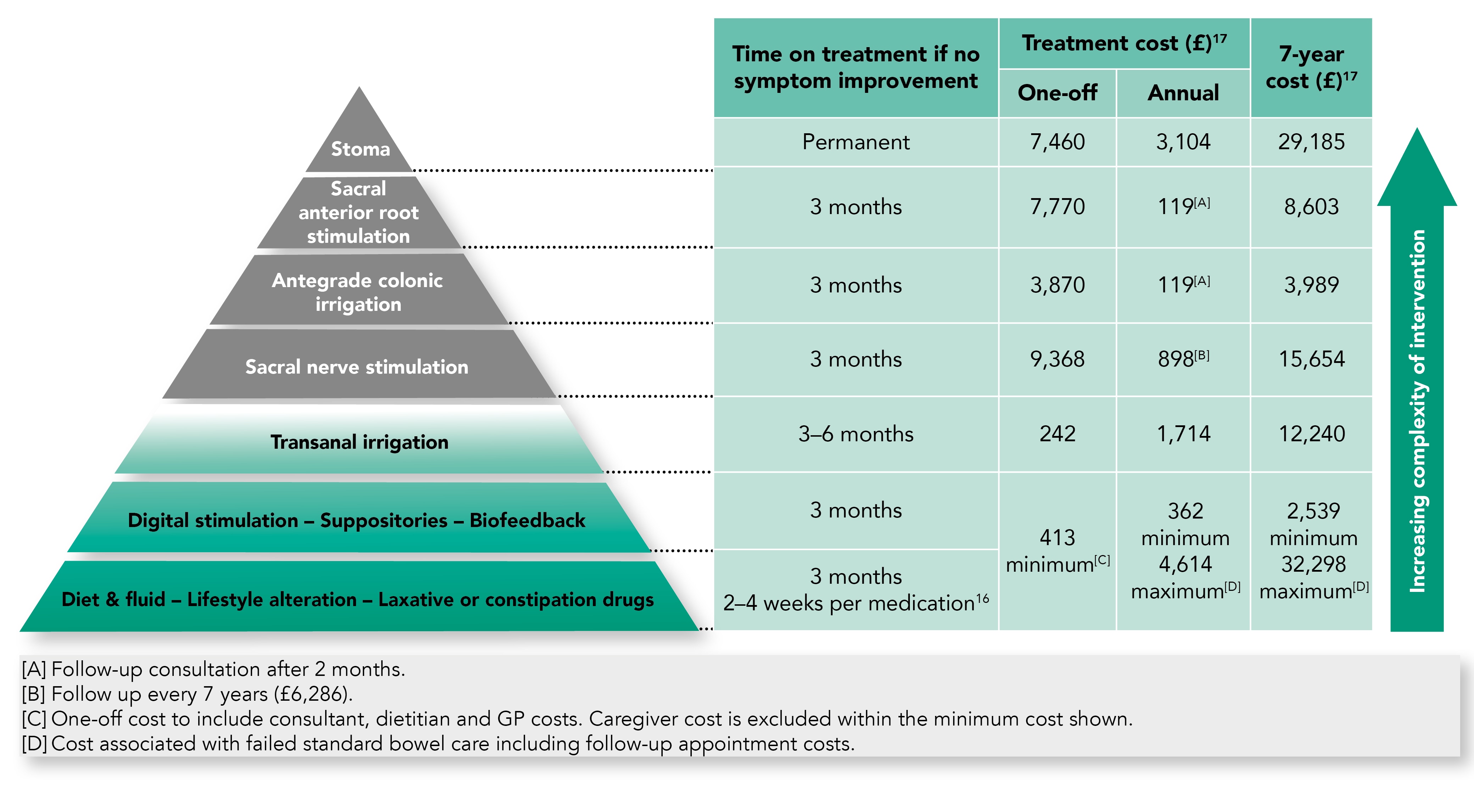

When GPs are unaware of other treatment possibilities, patients may be prescribed laxatives for too long rather than switching to a more effective treatment. For this reason, The Bowel Interest Group’s ‘Bowel dysfunction treatment pyramid’ (see Figure 1) presents the range of treatment options for patients with constipation, and a recommended timeframe for testing each one.

The pyramid also presents the one-off and long-term financial impact of each option, clearly depicting the escalation of costs when patients are kept on the same treatment beyond the recommended timeframe.

Bowel Interest Group. Dealing with chronic constipation: information for general practitioners. BIG, 2020. Available at: bowelinterestgroup.co.uk/resources/dealing-with-chronic-constipation-information-for-general-practitioners

6. Know Where to Look for More Information

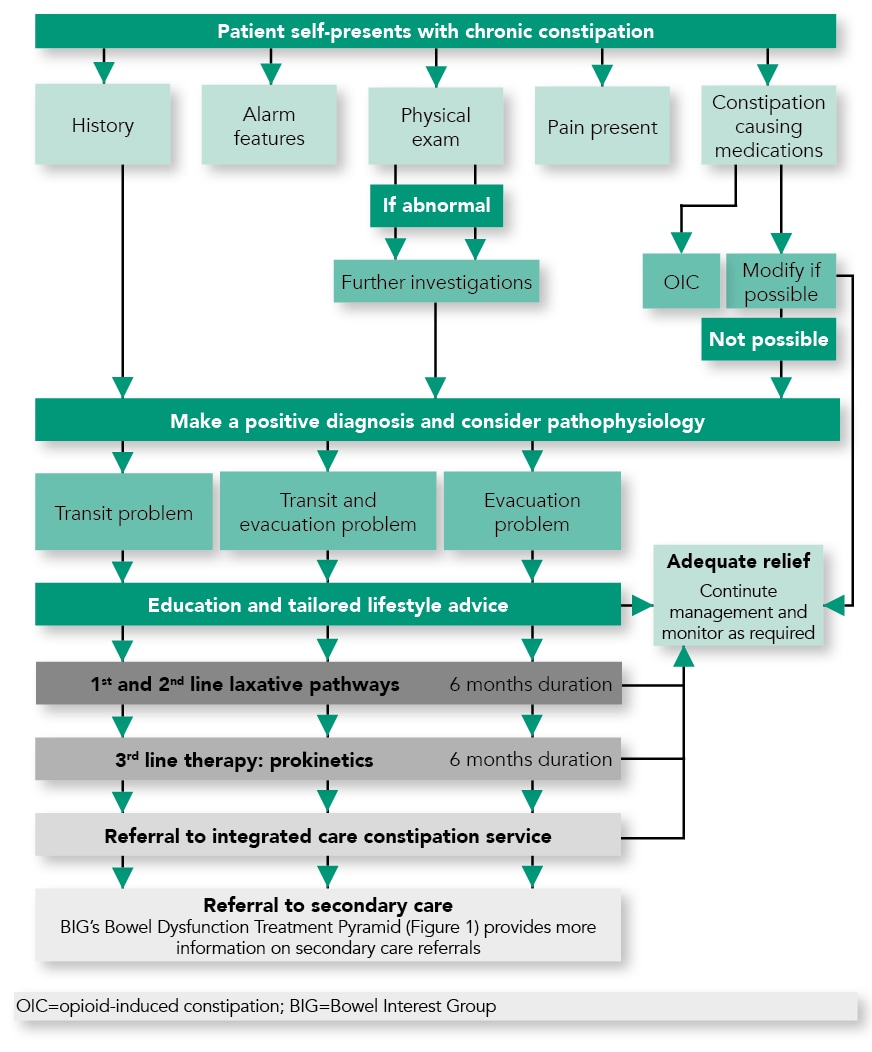

A lack of adequate information on constipation aimed at primary care is another key challenge. The Bowel Interest Group has built up a useful repository of resources for clinicians to help fill this gap.19 In particular, one valuable tool to support GPs during consultations is the group’s interactive treatment pathway (see Figure 2 for a static version).20 The pathway is structured as a guide that practitioners can click through as they ask questions. This ensures that each consultation is as thorough as possible, that the GP can better focus on the patient, and that they come to the most appropriate treatment option.

Bowel Interest Group. Interactive treatment pathway for chronic constipation. BIG, 2020. Available at: bowelinterestgroup.co.uk/resources/bigs-interactive-treatment-pathway-for-chronic-constipation

Professor Anton Emmanuel

Consultant Gastroenterologist, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the National Hospital for Neurology & Neurosurgery