Dr Michael Sproat uses Five Hypothetical Case Studies to Explore Possible Causes of a Change in Bowel Habit and How to Diagnose and Manage These in Primary Care

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find COVID-19 considerations at the end of this article |

Lower gastrointestinal symptoms are very common, accounting for approximately 1 in 12 of all GP consultations.1 Patients may present with diarrhoea, constipation, or alternating bowel habit with both looser and harder stools. Other symptoms can include abdominal discomfort, bloating, weight loss, rectal mucus, and rectal bleeding.

This article aims to explore some of the most common and important conditions that can present with a change in bowel habit, with advice on first-line investigations and management in primary care, as well as guidance on when to consider specialist referral.

Case 1

A 28-year-old woman presents with a 2-year history of alternating bowel habit with both looser and harder stools. She also describes bloating and lower abdominal discomfort relieved by defecation. There is no rectal bleeding or weight loss.

Diagnosis

This case sounds strongly suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is a common condition with a reported prevalence of between 10% and 20% of the UK population2 and is more common in women.3,4 It most commonly affects people aged 20 to 30 years, although symptoms can persist long term with a significant prevalence also reported in older people.2,5–7

There are a number of criteria used to diagnose IBS, including those recommended by NICE clinical guideline 61 (see Box 1)2 and the Rome Criteria.8 Three main subtypes are recognised: constipation predominant IBS (IBS-C), diarrhoea predominant IBS (IBS-D), and IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M).8,9

| Box 1: NICE Diagnostic Criteria for IBS2 |

|---|

Healthcare professionals should consider assessment for IBS if the person reports having had any of the following symptoms for at least 6 months:

A diagnosis of IBS should be considered only if the person has abdominal pain or discomfort that is either relieved by defaecation or associated with altered bowel frequency or stool form. This should be accompanied by at least two of the following four symptoms:

Other features such as lethargy, nausea, backache and bladder symptoms are common in people with IBS, and may be used to support the diagnosis. © NICE 2017 Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

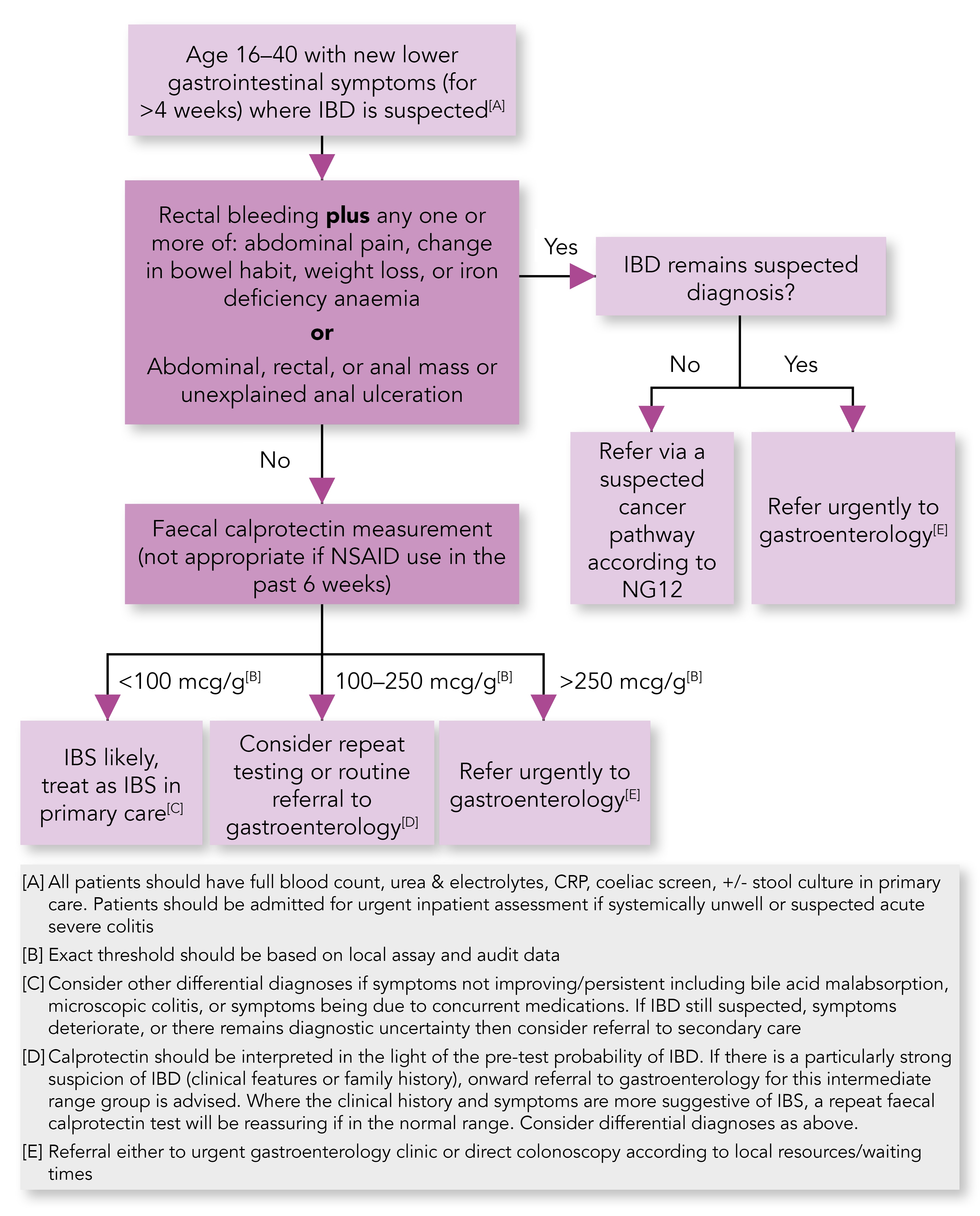

National guidelines recommend that all patients with suspected IBS should have blood tests, to assess full blood count (FBC), coeliac serology, and C-reactive protein (CRP).2,7 Additional blood tests to consider in patients presenting with diarrhoea include liver function tests, vitamin B12, folate, ferritin, calcium, and thyroid function;7 and, in patients presenting with constipation, thyroid function and calcium levels.10,11 Faecal calprotectin testing should also be considered in younger adults to help exclude inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (see Figure 1).3,12–14

Being able to make a clear diagnosis of IBS in patients with typical symptoms who meet diagnostic criteria is extremely helpful to facilitate patient understanding, reassurance, and to guide treatment. Such an approach also helps to avoid further invasive investigations such as colonoscopy which are not necessary to confirm a diagnosis of IBS in people who meet the diagnostic criteria.2

Atypical symptoms which may alert the clinician to potential organic disease include very frequent watery stools, incontinence, and nocturnal defecation. ‘Red flag’ indicators for more serious disease include unexplained weight loss, rectal bleeding, anaemia, palpable rectal or abdominal masses, or late age at onset of symptoms (over 60 years old).3,15

IBD=inflammatory bowel disease; NG=NICE guideline; NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; IBS=irritable bowel syndrome; CRP=C-reactive protein

Lamb C, Kennedy N, Raine T et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019; 68 (Suppl 3): s1–s106.

Management

Adopt a reassuring, patient-centred approach and, where possible, focus on developing a patient’s understanding of their condition and promoting the importance of self-management.

Alongside simple dietary advice (see Box 2), offer general lifestyle advice, such as strategies for managing stress.2 In many individuals with IBS, psychosocial stressors may play a more pivotal role than diet.5 Exclusion diets are not advised in all patients but can be helpful in some individuals where first-line dietary and lifestyle advice has not been successful. Advice about exclusion diets should be offered by a healthcare professional with expertise in dietary management.2,16 The British Dietetic Association also offers accessible information for patients about IBS and diet.17 Recent years have also seen a growing interest in probiotics, which can sometimes be helpful.18

In terms of medication, over-the-counter antispasmodics can be useful for the relief of abdominal discomfort.4,19 Laxatives are appropriate for IBS-C, and loperamide for IBS-D.2 Second-line treatment options include the use of low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) at a dose of 5–10 mg equivalent of amitriptyline taken at night, increasing the dose if needed but not usually beyond 30 mg,2 which if taken regularly can be particularly helpful for symptoms of urgency, loose stools, and abdominal pain.

| Box 2: General Dietary Advice for Adults with IBS2 |

|---|

Diet and nutrition should be assessed for people with IBS and the following general advice given.

© NICE 2017 Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

Case 2

A 34-year-old man attends the practice with an 8-week history of new-onset left lower abdominal pain associated with urgency, rectal mucus, and looser stools up to 6 times daily. Symptoms are affecting his sleep and attendance at work.

Diagnosis

The presentation of IBD and IBS can be similar, both in terms of symptoms and age of presentation, making clinical diagnosis difficult.3 In this case, however, the recent onset of symptoms and impact on normal daily activities increases the clinical suspicion of IBD.

Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract and can be divided into two types: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.14 If inflammation is limited to the rectum, the term proctitis may also be used. These conditions can develop at any age but the peak incidence of ulcerative colitis is between the ages of 15 and 25 years,20 and up to one-third of patients with Crohn’s disease are diagnosed before the age of 21.21

Management

Baseline blood tests and faecal calprotectin testing are advised (as discussed in case 1), and if the faecal calprotectin is elevated the patient should be referred to gastroenterology; direct referral to gastroenterology is also indicated if there is associated rectal bleeding or other red flag indicators (see Figure 1). In patients presenting with suspected colitis, stool cultures and Clostridium difficile toxin assay should also be performed to rule out infective causes.12,14

Unlike ulcerative colitis, which only affects the large bowel, Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. This can make diagnosis more difficult, with up to 20% of patients having isolated proximal small bowel disease beyond the reach of ileocolonoscopy (colonoscopy with terminal ileal biopsy).14 If significant clinical suspicion persists about possible Crohn’s disease, further assessment by secondary care Gastroenterology is advised to consider dedicated small bowel imaging.12,14 There is, however, a more limited role for faecal calprotectin testing in older adults, especially those aged over 50 years where the higher prevalence of other conditions (colorectal cancer in particular) favours direct referral for colonoscopy or a faecal immunochemical test (FIT) instead—see case 4.

Patients with IBD typically experience periods of relapse and remission. Management is focused on treating both acute flare-ups and maintaining remission. Screening colonoscopies are also required for patients with long-term IBD due to an increased risk of colorectal cancer.14

For more information on the management of IBD in primary care, refer to previous Guidelines in Practice articles about related guidance:

- Inflammatory bowel disease: NICE updates advice on remission, by Sarah Cripps22

- The new BSG guideline on inflammatory bowel disease and the role of the GP, by Dr Kevin Barrett.23

Case 3

A 48-year-old man presents with a 9-month history of fatigue. On discussion, he also reports a more longstanding history of abdominal bloating and an irregular bowel habit attributed to IBS. Blood test results show iron deficiency anaemia.

Diagnosis

This case is typical of coeliac disease, in which individuals develop inflammation and villous atrophy of the small intestine following the ingestion of gluten.

Coeliac disease has an estimated prevalence of approximately 0.5–1% in the UK population,12 and can present with a wide range of clinical features. National guidelines recommend that coeliac serology is always checked in patients with persistent gastrointestinal symptoms2 as well as in those with faltering growth, prolonged fatigue, unexplained weight loss, severe or persistent mouth ulcers, or deficiency in iron, vitamin B12, or folate.24 Screening should also be offered to asymptomatic individuals who have type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroid disease, or if they have a first-degree relative with coeliac disease.24

IgA tissue transglutaminase (IgA TTG) and IgA endomysial antibodies (IgA EMA) have a combined sensitivity and specificity of over 90% for coeliac disease.12,25 Despite this, duodenal biopsy remains the recommended approach to confirm the diagnosis in all adults with positive serology;12,24 however, this is now the subject of review, with interim guidance issued in June 2020 by the British Society of Gastroenterology, which supports making a clinical diagnosis of coeliac disease without biopsy in some instances—see the COVID-19 considerations box.

Importantly, testing is only accurate if the individual continues a normal diet for at least 6 weeks prior to testing, ensuring that gluten is included in more than one meal every day.24 However, 2% of patients with coeliac disease are IgA deficient which may also lead to false negative blood tests and a reduction in the sensitivity of serological testing.26 If patients are known to be IgA deficient, IgG-based antibodies should be used,12 or they should be referred directly to oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) and diagnostic duodenal biopsy.26

Management

All individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of coeliac disease should be advised on the importance of long-term adherence to a gluten-free diet.24 Additional advice and support is also available from charities such as Coeliac UK.27

NICE recommends an annual review in primary care to check dietary adherence and screen for any signs or symptoms of active coeliac disease.24 It includes advice to monitor weight and height, assess risk of osteoporosis, and consider annual blood tests. Appropriate blood tests include repeat coeliac serology, FBC, ferritin, thyroid function tests, liver function tests, vitamin D, vitamin B12, folate, calcium, and electrolytes.26

Consider referral to a dietitian at diagnosis or on follow-up if there is difficulty in assessing adherence to a gluten-free diet, or if poor adherence is suspected.24

Case 4

A 68-year-old woman reports a 3-month history of change in bowel habit and a loss of 7 kg of weight. On discussion she also mentions bloating and abdominal discomfort. There is no rectal bleeding.

Diagnosis

This woman requires a 2-week wait urgent referral for either colonoscopy or computed tomography (CT) colonography to exclude colorectal cancer (see Box 3 for full referral criteria). The differential diagnoses include ovarian and pancreatic malignancy.15

| Box 3: Urgent Referral Criteria for Colorectal Cancer15 |

|---|

Refer adults using a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) for colorectal cancer if: they are aged 40 and over with unexplained weight loss and abdominal pain or they are aged 50 and over with unexplained rectal bleeding or they are aged 60 and over with:

© NICE 2017 Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. |

Screening blood tests, such as FBC, electrolytes, liver funtion tests, thyroid function, coeliac serology, CRP, and CA125 can be useful for ruling out other causes of her change in bowel habit. Urgent direct access CT of the pancreas (or an urgent ultrasound scan if CT is not available) should also be considered to exclude pancreatic cancer in people aged 60 years and over who present with weight loss and any of the following symptoms:15

- diarrhoea

- back or abdominal pain

- nausea

- vomiting

- constipation

- new-onset diabetes.

For patients who do not meet the criteria for a 2-week urgent referral for suspected cancer, NICE recommends an initial FIT to assess the need for colonoscopy (see Box 4).15,28 Routine colonoscopy may still be indicated if symptoms persist, in order to exclude non-malignant conditions such as diverticular disease.28

| Box 4: Faecal Occult Blood Testing28 |

|---|

NICE’s guideline on suspected cancer previously recommended that faecal occult blood tests should be offered to adults without rectal bleeding who:

The faecal occult blood tests were recommended in NICE’s guideline on suspected cancer to triage referral to secondary care. The tests were intended to be used in selected groups of people who have symptoms that could suggest colorectal cancer, but in whom a definitive diagnosis of cancer was unlikely. That is, they had a low probability of having colorectal cancer (their age and symptoms have a positive predictive value of between 0.1% and 3% for colorectal cancer). If a faecal occult blood test was positive, NICE’s guideline on suspected cancer recommended that people in England should be referred using a suspected cancer referral to establish a diagnosis. Faecal occult blood can be caused by conditions other than colorectal cancer, such as colorectal polyps and inflammatory bowel disease, so further assessment with a colonoscopy is needed to diagnose colorectal cancer; a positive faecal occult blood test was not intended be used alone. © NICE 2017 Quantitative faecal immunochemical tests to guide referral for colorectal cancer in primary care. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg30 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. |

Management

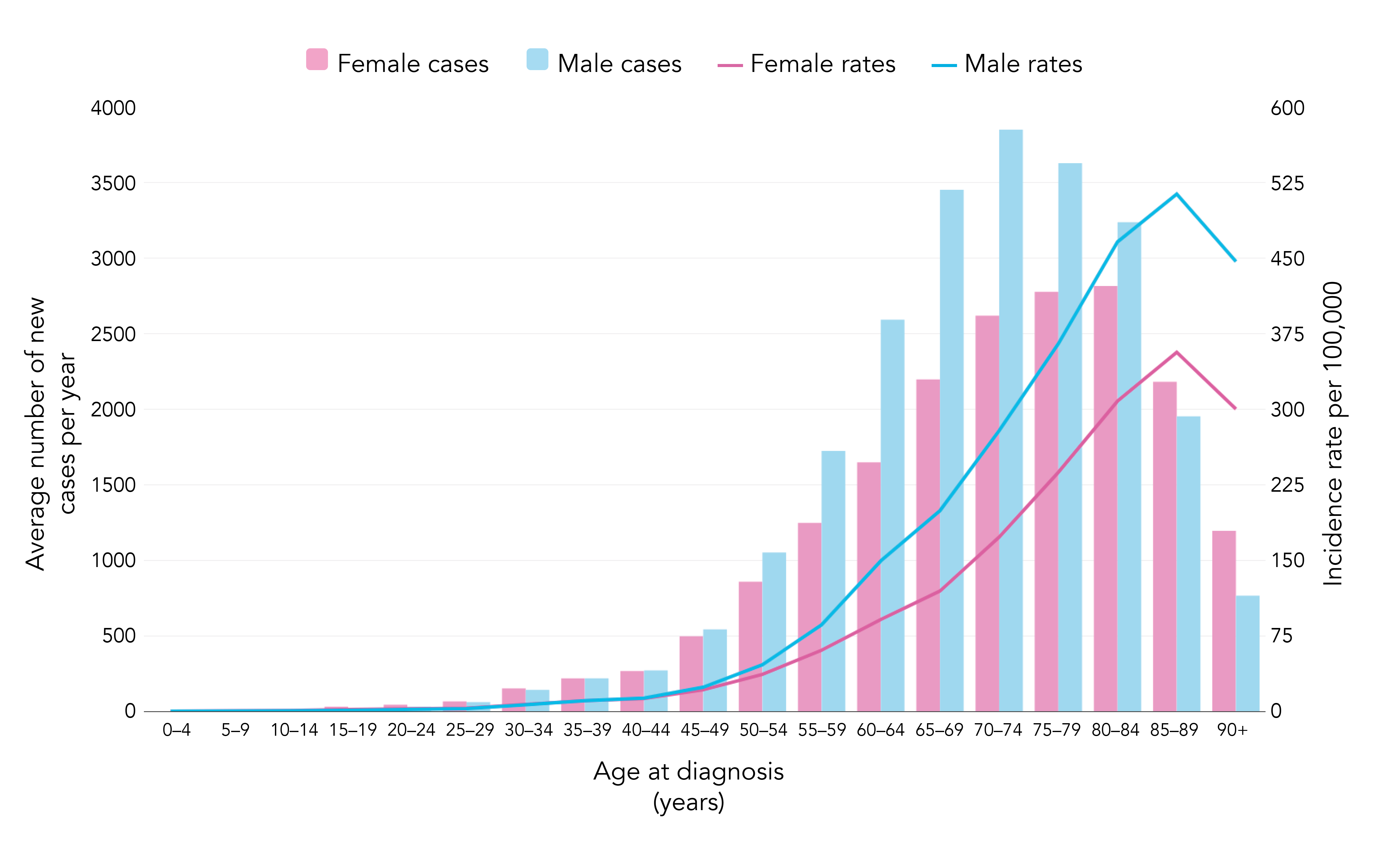

Bowel cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the UK.29 Bowel cancer incidence is strongly related to age; incidence rates rise steeply from around age 50–54 years. The highest rates are in the 85–89 age group for females and males (see Figure 2). The NHS Long Term Plan emphasising making a diagnosis at an earlier stage of the disease.30 Recent years have also shown an increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults31,32 and clinicians should therefore remain mindful of this condition in any patient who presents with atypical symptoms, and refer appropriately to secondary care.

Cancer Research UK. Bowel cancer incidence statistics. www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer/incidence (accessed 26 August 2020).

Case 5

A 62-year-old woman describes a change in bowel habit to loose, watery stools associated with urgency and incontinence, which started around 4 months ago. She has not experienced any weight loss, bloating, or abdominal pain. These difficulties follow a very difficult 12-month period, during which she started taking sertraline for anxiety.

Diagnosis

The patient has microscopic colitis secondary to sertraline. This case has been included to highlight the broad range of conditions that clinicians must consider in patients describing a change in bowel habit. In this situation, it would be common for clinicians to suspect a diagnosis of IBS exacerbated by anxiety and stress. However, the presence of very watery stools and incontinence is unusual for IBS, while the patient also does not describe any abdominal pain or bloating, which would be expected in IBS (see Box 1).

Management

Recommended management includes urgent referral for colonoscopy to exclude colorectal cancer.15 Importantly, the colonic mucosa appears normal in patients with microscopic colitis; therefore, right and left colonic biopsies are required in all patients undergoing colonoscopy for unexplained diarrhoea.12,33

Microscopic colitis causes chronic watery diarrhoea with a median age at diagnosis of 59 years.34 It is more common in women and current smokers,35 and is associated with a number of medications including selective serotonin uptake inhibitors such as sertraline, proton pump inhibitors, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.34,35 Autoimmune disease, especially coeliac disease, is also associated with microscopic colitis.34,35

The principal management, if appropriate, is to identify and stop any triggering medication. If no clear cause is identified, however, symptoms often respond well to a short course of oral budesonide.35

Summary

There are a wide range of potential causes to consider in an individual who presents with a change in bowel habit. A large proportion of these cases are functional, although clinicians need to remain vigilant for serious causes such as IBD and malignancy. A careful, detailed history should be taken to enquire about atypical symptoms and red flags, with reassessment if symptoms change. The list of conditions discussed here is not exhaustive. Seek specialist advice if unexplained or concerning symptoms persist despite normal first-line investigations and treatment.12

Dr Michael Sproat

GP, Bristol

| COVID-19 Considerations | |

|---|---|

|