Dr Umesh Dashora and Colleagues from the CaReMeUK Partnership Outline Guidance on How to Manage Type 2 Diabetes with Cardiovascular and Renal Disease

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

A version of this article, adapted for a secondary-care audience, was published in Clinical Medicine 2021; 21: 204–210. |

In people with diabetes, the presence of multiple co-morbidities—such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), renal dysfunction, and metabolic disease—is common,1,2 and the prevalence of cardiovascular multimorbidity has significantly increased in modern times.3 Unfortunately, the management of these conditions remains fragmented between different specialties, and there is often a gap in communication between healthcare professionals about the care of individuals with these problems. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop a joined-up approach.

The Cardio-Renal-Metabolic (CaReMeUK) Partnership is a collaboration between the British Cardiovascular Society, the Renal Association, and the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists. These three professional societies—along with the Primary Care Cardiovascular Society and the Primary Care Diabetes Society—have formed the CaReMe UK Partnership, bringing together expertise from across primary and secondary care with the aim of improving the management of people with multiple co-morbidities.

Recent cardiovascular (CV) outcomes trials have established the significant CV and renal benefits of sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs).4–19 The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology/EASD have already prioritised the use of SGLT2is and GLP-1 RAs in certain patient groups (such as those with atherosclerotic CVD, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease [CKD]) in their recommended treatment algorithms.20–22 NICE guidelines for the management of people with type 2 diabetes date from 2015 and do not take into account the data from recent cardiovascular outcomes trials, although NICE is due to publish an update in future.23

The CaReMeUK Partnership met virtually many times to discuss the recent evidence. After much deliberation, the group agreed on a number of algorithms and guides for healthcare professionals to improve the management of people with diabetes, CVD, and renal disease, and a leaflet and booklet for people with diabetes on appropriate and safe use of medications.24

This article explains the CaReMeUK Partnership consensus guidance on the management of people with type 2 diabetes, based on the current evidence.

The Importance of Diagnosing the Type of Diabetes Correctly

Diabetes is diagnosed by a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥7 mmol/l or a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of ≥48 mmol/mol on one occasion in the presence of symptoms, or on two occasions in asymptomatic people.25

People with type 1 diabetes are dependent on insulin for their survival. It is important to make an accurate distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes because those who have the former are at high risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and harm if their insulin is reduced or stopped, and treatment is with SGLT2is or GLP-1 RAs only.

If a person with apparent type 2 diabetes does not have the typical phenotype or characteristics of type 2 diabetes (for example, overweight, late onset), specialist advice may be needed to exclude the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (by antibody tests and C-peptide levels).

People with type 2 diabetes have significant endogenous insulin production, but are characterised by high insulin resistance and are at high risk of CV and renal disease; in the case of CV co-morbidities, an almost twofold increase in the risk of mortality and a reduction in life expectancy of around 12 years were evident in patients aged 60 years with any two of the following conditions: diabetes mellitus, stroke, and myocardial infarction (MI).26 People with type 1 diabetes are also at increased risk of cardiac and renal complications compared with the general population,27–29 but the number of people living with type 1 diabetes is lower, and the resultant economic burden can be expected to be smaller, than that of people with type 2 diabetes.30

The Need for a Cardio–Renal–Metabolic Pathway for the Management of Diabetes, CVD, and Renal Disease

Clinical outcomes for most patients with CVD have improved substantially over time, but outcomes in patients with CVD and diabetes remain poorer than those without diabetes—for example, improvements in the management of MI in recent decades have not reduced the gap in outcomes following MI between patients with and without diabetes.31 A glucose-based approach to the management of diabetes has only a modest impact on the risk of macrovascular events, and causes no significant reduction in CV mortality.32

SGLT2is improve CV and renal outcomes.4–12 A number of SGLT2is are recommended by guidelines and have received licences for indications such as heart failure and renal impairment. Based on clinical trial data, many of these drugs are indicated in people with risk factors or established CV or renal disease, irrespective of their HbA1c or diabetic status and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). SGLT2is may not be suitable for a minority of people with type 2 diabetes;33,34 please check the up-to-date licences and Summaries of Product Characteristics (SPCs).35–38

GLP-1 RAs also reduce major adverse CV events, hospitalisation for heart failure, and poor renal outcomes.13–19 Recognition of the major CV and renal benefits of these drugs has led to a change in the focus of international guidelines, in which SGLT2is and GLP-1 RAs are now prioritised ahead of other glucose-lowering therapies, regardless of HbA1c thresholds, in patients with type 2 diabetes and CVD.20–22

However, data from the National Diabetes Audit suggest that targets for glycaemia, blood pressure, and lipids are met in only a minority of individuals,39 indicating room for improvement in the management of diabetes and co-morbidities. In one hospital, an audit of patients with type 2 diabetes 1 year after hospital admission for MI found that HbA1c was above target in more than half of these patients; most were eligible for treatment with an SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA, but were not receiving one of these agents.40

In contrast to international diabetes guidelines, current NICE guidance on the management of type 2 diabetes in adults was published in 2015, and has not yet been updated to reflect the accumulating evidence for CV risk reduction.23 In many regions, local guidelines are now similarly outdated, highlighting the pressing need for individual regions across the UK to develop and implement their own cardiometabolic pathways. Until updated diabetes guidance is available from NICE, local initiatives are needed to drive improvements in CV risk management in patients with diabetes.

Supplementing a traditional ‘glycaemia-based’ diabetes management pathway with a cardiometabolic pathway focused on increasing uptake of SGLT2is and GLP-1 RAs, irrespective of HbA1c, has the potential to reduce CV events and mortality.4–19 Treatment recommendations should be evidence-based, and CV and renal risk reduction must override other considerations, such as acquisition cost. In this setting, the acquisition cost of SGLT2is is similar to that of the most commonly prescribed alternative, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is).41 Modelling based on the local population can reflect the downstream cost savings resulting from a reduction in costly clinical events (primarily admissions for heart or kidney failure) afforded by SGLT2i therapy. The cost-effectiveness of treatment with empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, taking into account the reduction in clinical events, has been considered by NICE in its related Technology Appraisals.42,43

Key Guidance

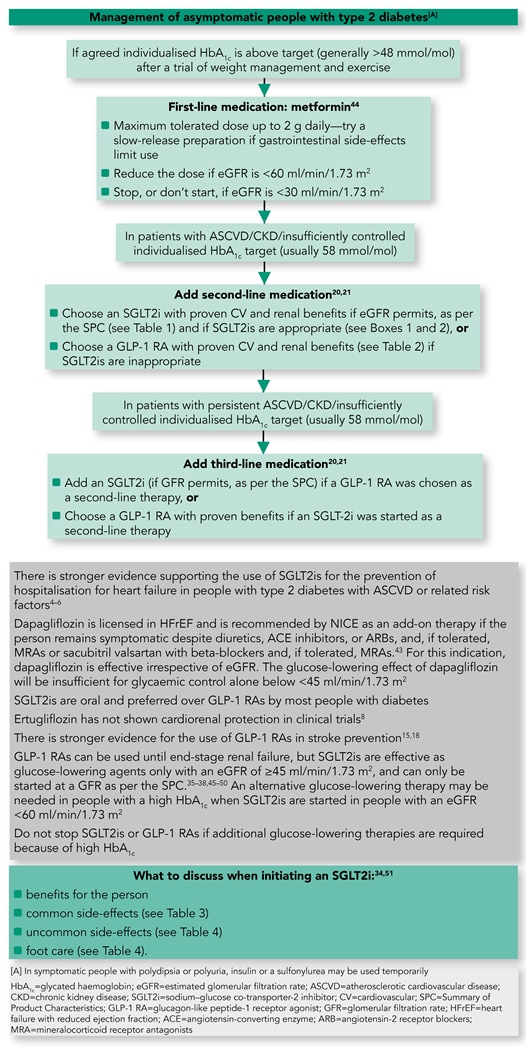

The management of asymptomatic individuals with type 2 diabetes, taking into account recent data from CV outcome trials, is presented in an algorithm in Figure 1.

Table 1: Summary of Licensed Indications and Recommended Doses of SGLTis in Type 2 Diabetes34

| Dose Adjustment Recommendations Based on Kidney Function ml/min/1.73 m2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i | Licensed indication | eGFR >60 | eGFR 45–59 | eGFR 30–44 | eGFR <30 |

| Canagliflozin35 | Adults with insufficiently controlled type 2 diabetes | Initiate 100 mg; titrate to 300 mg if needed | Initiate/continue with 100 mg only | Initiate/continue with 100 mg only if urinary albumin:creatinine ratio >300 mg/g | Continue at 100 mg for reno-protection until dialysis/transplant |

| Dapagliflozin36 | Adults with insufficiently controlled type 2 diabetes | Initiate 10 mg | Continue with 10 mg for reno-protection only. Do not initiate | Not recommended | |

| HFrEF with or without type 2 diabetes | Initiate 10 mg | Limited experience | |||

| Empagliflozin37 | Adults with insufficiently controlled type 2 diabetes | Initiate 10 mg; titrate to 25 mg if required | Continue with 10 mg only. Do not initiate | Not recommended | |

| Ertugliflozin38 | Glycaemic control only | Initiate 5 mg; titrate to 15 mg if needed | Continue with 10 mg only. Do not initiate | Not recommended | |

Key: green=initiate; yellow=initiate in certain circumstances; orange=do not initiate but can continue established treatment; red=treatment not recommended In appropriate high-risk patients, a decision to treat with an SGLT2i to reduce the risk of CV, kidney, and/or heart failure events should be considered independently of HbA1c:

Further trial results on CKD and heart failure are in the pipeline, which may impact licensed indications in future. Please refer to the current SPCs for individual drugs for the latest information on licensed indications and dose-adjustment recommendations. | |||||

| Box 1: Who is the Ideal Candidate for SGLT2i Treatment?34 |

|---|

It is important to select the right patient for SGLT2i therapy and to avoid it in others who may be at high risk of DKA.33,34 The following patients are likely to benefit most:

SGLT2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; DKA=diabetic ketoacidosis; CVD=cardiovascular disease; CKD=chronic kidney disease |

| Box 2: When to Exercise Caution When Using an SGLT2i34,51 |

|---|

SGLT2is should be used with caution in the following situations:

SGLT2is should be avoided in the following situations:

Seek advice from the local diabetes team if unsure about the benefits and risks Note A: Dapagliflozin 5 mg is licensed for use in type 1 diabetes in certain circumstances, but should only be initiated and supervised by a specialist36 SGLT2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; BMI=body mass index; HbA1c =glycated haemoglobin; DKA=diabetic ketoacidosis; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; LADA=latent autoimmune diabetes Adapted with permission from Umesh D, Gregory R, Winocour P et al. Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and Diabetes UK joint position statement and recommendations for non-diabetes specialists on the use of sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in people with type 2 diabetes (January 2021). Clin Med 2021; 21 (3): 1–7. |

Table 2: Summary of Current Licensed Indications and Recommended Doses of GLP-1 RAs in Type 2 DiabetesA

| Dose Adjustment Recommendations Based on Kidney Function ml/min/1.73 m2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 RAs | Licensed indication | eGFR >60 | eGFR 45–59 | eGFR 30–44 | eGFR <30 | eGFR <15 |

| Lixisenatide45,53 | Adults with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes on OAD or basal insulin or both Starting dose 10 mcg (day 1–14) Maintenance dose 20 mcg | |||||

| Liraglutide46 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus—monotherapy (if metformin inappropriate) or in combination with other antidiabetic drugs Starting dose: 0.6 mg once daily for a week Maintenance dose: 1.2 or 1.8 mg daily | |||||

| Semaglutide47 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus monotherapy (if metformin inappropriate) or in combination with other antidiabetic drugs Starting dose: 0.25 mg once weekly for 4 weeks Maintenance dose 0.5–1 mg once weekly | |||||

| Exenatide QW48 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus in combination with metformin or an SU or both, or with TZD, or with both metformin and TZD in people not achieving glycaemic control 2 mg once weekly | Avoid if eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 | ||||

| Dulaglutide49 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus—monotherapy (if metformin inappropriate) 0.75 mg or in combination with other antidiabetic drugs if inadequately controlled 1.5–4.5 mg once weekly | |||||

| Oral semaglutide50 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus—monotherapy (if metformin inappropriate) or in combination with other antidiabetic drugs Starting dose: 3 mg once daily for 1 month Maintenance dose 7–14 mg once daily | |||||

| Key: green=suitable for use; yellow=use with caution; red=treatment not recommended | ||||||

| Note A: Consult individual SPCs because the licensed indications may have changed since the production of this table | ||||||

| GLP-1 RA=glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; OAD=oral antidiabetic agent; QW=once weekly; SU=sulfonylurea; TZD=thiazolidinedione; SPC=Summary of Product Characteristics | ||||||

Table 3: Common Adverse Reactions to SGLT2is34–38

| Adverse Reaction | Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genital mycotic infections | Common/very Common | Men and women. Provide genital hygiene advice. Most initial cases can be treated with topical antifungals and won’t recur. Consider reviewing therapy for recurrent infections |

| Increased urination | Common | Increased frequency and/or increased volume |

| Urinary tract infections | Common | In recent large trials, any increase in risk was small and non-significant |

| Volume-depletion side-effects (thirst, postural dizziness, hypotension, dehydration) | Common/uncommon (varies with agent) | Caution in frail/elderly. Consider measuring blood pressure in the lying and standing positions in those at risk of a fall and in those on diuretics |

| Frequency categories: very common: ≥1/10; common: <1/10 to ≥1/100; uncommon: <1/100 to ≥1/1000; Rare: <1/1000 to ≥1/10,000 | ||

Table 4: Uncommon but Serious Adverse Reactions with SGLT2is34–38,54,55

| Adverse reaction | Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DKA | Event rate <1/1000 in SPC (between 0 and 2 additional events/1000 person-years in RCTs); real-life events may be higher |

|

| Amputation | Event rate <1/100 in SPC (between 0 and 3 additional events/1000 person-years in RCTs)A; real-life events may be lower |

|

| Note A: Excess amputations were only seen with canagliflozin in the CANVAS study.4 Subsequent studies with the same SGLT2i and others have not confirmed a significant increase. Any risk is likely to be very low. Necrotising fasciitis (Fournier’s gangrene): post-marketing reports have been reported (six yellow card reports in >500,000 patient–years. Recent meta-analysis of clinical trials find the association uncertain.56 Patients should be advised to seek urgent medical attention if they experience fever/malaise along with pain, tenderness, or redness in the genital or perineal area.34,57 SGLT2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; DKA=diabetic ketoacidosis; SPC=Summary of Product Characteristics; RCT=randomised controlled trial | ||

Second-line Medications that can Improve CV and Renal Outcomes in People with Type 2 Diabetes

Second-line therapies for diabetes can be selected for their cardiorenal benefits irrespective of HbA1c.20,21 These medications can also be selected when metformin is either inappropriate or insufficient to keep HbA1c below the agreed individualised target (usually 48 mmol/mol for monotherapy, 58 mmol/mol for dual therapy, or higher for people who are frail or have DKD [58–68 mmol/mol for CKD stage 3–4 and CKD stage 5 on dialysis]).58

In general, all people will benefit from an SGLT2i as a second-line therapy, except when it is inappropriate (for example, the patient has a history of DKA, foot problems, or fractures) or when there is a more appropriate drug in a particular situation (for example, GLP-1 analogues in stroke risk). The other option is a GLP-1 RA with proven CV and renal benefits, except when it is inappropriate (for example, in patients with pancreatitis, severe retinopathy, or biliary issues). If neither is appropriate, consider:20,21

- pioglitazone, except when inappropriate because the patient has fractures, macular oedema, or heart failure

- a DPP-4i, except when inappropriate because the patient has pancreatitis, biliary issues, or heart failure in the case of saxagliptin

- a sulfonylurea (SU), except when inappropriate because of hypoglycaemia risk

- insulin, except when inappropriate because of high hypoglycaemia risk.

Other factors to consider include patient preference for injectable or oral therapy, and current licensing restrictions in relation to GFR. See Table 5 for specific cautions to consider when choosing a second-line therapy.

Table 5: How to Choose a Second-line Medication34

| Scenario (Presence of Risk) | SGLT2i | GLP-1 RA | Pioglitazone | DPP-4i | SU | Insulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD | ||||||

| DKD | 1, 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | ||

| Heart failure | 16 | 2,15 | 3,16 | 15 | ||

| Foot disease with vascular complications or sepsis | 9 | |||||

| Stroke or TIA | ||||||

| History of DKA | ||||||

| Pancreatitis | 4 | |||||

| Osteoporotic fracture | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Overweight | ||||||

| Hypoglycaemia risk | ||||||

| Retinopathy | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Symptomatic hyperglycaemia | ||||||

| Cost | ||||||

| Bladder health | 10 | 11 | ||||

| Biliary health | 12 | |||||

Key: green=preferred option for second-line medication; yellow=specific cautions apply; red=not the preferred option The following numbers indicate the specific cautions that should be taken into account when choosing a therapy:59

SGLT2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; GLP-1 RA=glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; DPP-4i=dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; SU=sulfonylurea; CAD=coronary artery disease; DKD=diabetic kidney disease; TIA=transient ischaemic attack; DKA=diabetic ketoacidosis; SPC=Summary of Product Characteristics; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD=chronic kidney disease; GLP-1=glucagon-like peptide-1 | ||||||

What Should the Prescriber Know or Do When Starting SGLT2i Therapy?

When initiating SGLT2i treatment in a patient with type 2 diabetes, the prescriber should:34

- document the completion of the education session with the person with diabetes

- advise who can be contacted if the person taking SGLT2i is not feeling well

- consider reducing the dose of any other glucose-lowering medications, such as insulin and SUs

- consider the risk of DKA if insulin requirement reduces considerably

- review diuretics and anti-hypertensive therapy, especially in elderly individuals at risk of dehydration or postural hypotension.

DKA Essentials for Primary Care Healthcare Professionals

Check blood ketones in people who are taking an SGLT2i and not feeling well. Metabolic decompensation may progress from ketonuria to ketosis and finally to ketoacidosis, requiring urgent treatment to prevent mortality. Blood ketone testing may only be possible at the nearest hospital because most people with type 2 diabetes and most surgeries will not have a ketone meter. If blood ketones are greater than 1.5 mmol/l or if the blood ketones measurement is unavailable, venous blood gases may need to be checked to confirm DKA.60 Once diagnosed, treat DKA according to the Joint British Diabetes Society guidelines60 or a locally adapted protocol. Glucose as well as insulin may be needed for SGLT2i-induced euglycaemic DKA.60

How Can You Encourage Your Patients on SGLT2is to Reduce Their Risk of DKA?

To reduce their risk of DKA, patients taking an SGLT2i should be encouraged to:

- avoid known precipitating factors for DKA, such as starvation or alcohol abuse61

- at times when oral intake is poor, ensure hydration and, if taking insulin, take half of the normal dose of insulin. Stop taking SGLT2is when feeling unwell and unable to eat and drink51

- check for ketones (blood ketones are preferable to urine ketones) and seek help with symptoms suggestive of DKA (vomiting, abdominal pain, drowsiness, fatigue, and hyperventilation)51

- stop taking an SGLT2i 24 hours before elective surgery requiring starvation and restart 24–48 hours after normal oral intake—which may take 1–2 weeks—or follow the advice from the healthcare professionals.34,51,61 More information is available on the British Cardiovascular Society website.24

When to Stop and Restart SGLT2is

Sometimes, it may be necessary to stop SGLT2is to reduce the risk of DKA.33,51 After an episode of DKA, SGLT2is should not be restarted at a future time because the episode may reflect poor beta cell reserve.61

Suspend SGLT2is in the following circumstances:51

- acute medical admission with severe illness, including COVID-19

- admission for elective surgery or a procedure requiring starvation

- vomiting

- dehydration

- acute diabetic foot problems.

Restart only after the patient is back to normal and eating and drinking.62 Alternative glucose-lowering therapy may be needed during this period of interruption.

Suggested Approaches to Implementing Best Practice

Uptake of the 2021 CaReMeUK Partnership consensus guidance on the management of diabetes, CVD, and renal disease will be assisted by:

- local champions and enthusiasts

- involvement of pharmacists

- presentations to CCGs/stakeholders

- support from national professional bodies

- action at all contact—an approach recommended by a best practice guide developed through the British Cardiovascular Society by a CaReMeUK team is that patients should be identified and considered for a therapy review at any relevant clinical contact, whether in primary or secondary care33

- local agreement on who will initiate treatment with these medications

- leaflets and resources for both healthcare professionals who are not specialists in diabetes and for people with diabetes33,51

- dedicated cardiometabolic clinics run jointly by specialists in diabetes, cardiology, and renal medicine.

Summary

Management of people with multiple co-morbidities including diabetes and cardiovascular diseases has transformed in recent times. Clinical trials and international guidelines suggest earlier use of SGLT2is and GLP-1 RAs with proven evidence in the treatment algorithms to improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes in eligible people. Comprehensive education and appropriate use of these medications at all possible patient contacts can make a considerable difference to the health outcomes of our population.

Dr Umesh Dashora, Professor Stephen B Wheatcroft, Dr Peter Winocour, Dr Jim Moore, Professor Ahmet Fuat, Professor Ketan Dhatariya, and Dr Dipesh Patel on behalf of the CaReMeUK Partnership

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; SGLT2i=sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; GLP-1 RA=glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |