Muhammad Siddiqur Rahman discusses updated advice on blood pressure targets in patients with CVD, and offers 10 top tips on the detection and treatment of hypertension

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points, implementation actions for STPs and ICSs, and implementation actions for clinical pharmacists in general practice at the end of this article |

Hypertension is defined by the World Health Organization as a condition in which the blood vessels have persistently raised pressure.1 Around one-third of adults in the UK are thought to be living with high blood pressure (BP), equating to around 15 million people.2–4 However, the estimated prevalence of hypertension varies widely at the GP practice level as a result of differences in demographic characteristics between practice populations, such as age and socioeconomic status, and can range from 18.8—31%.4

An estimated 6–8 million people in the UK are currently living with undiagnosed or untreated high BP.3 Hypertension is the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the UK,3 and uncontrolled high BP increases the risk of CVD and macrovascular complications of heart disease.2 Around 50% of heart attacks and strokes are linked to hypertension.3 In 2020, coronary heart disease was the third biggest cause of death in the UK (after COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia) and accounted for over 64,000 deaths, equivalent to approximately one death every 8 minutes.3

High BP costs the NHS up to £2.1 billion a year.5 There are also around 7.6 million people currently living with CVD in the UK, whose healthcare costs are estimated to total £9 billion a year.3

The Updated NICE Guideline on Hypertension in Adults

When it was first published in 2019, NICE Guideline (NG) 136, Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management, identified a clinic BP target of less than 140/90 mmHg (or an average home blood pressure monitoring [HBPM] or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring [ABPM] target of less than 135/85 mmHg) as appropriate for adults aged under 80 years with hypertension.5,6 The clinic BP target for patients with hypertension aged over 80 years was slightly higher, at less than 150/90 mmHg (or an average HBPM or ABPM of less than 145/85 mmHg).5,6 The guideline stated that clinical judgement is required for BP targets in patients with frailty and/or multimorbidity.5 However, the 2019 recommendations did not account for patients with both hypertension and established CVD.6

Given that people with established CVD are at higher risk of CVD events than those without, NICE stated in an evidence review that ‘further reduction in blood pressure beyond those recommended in NG136 might confer a level of benefit which exceeds any associated adverse effects’.6 Thus, in March 2022, NICE updated NG136 to provide new recommendations on BP targets for patients with hypertension and established CVD.5 The updated guideline states that the same BP targets should be used for patients with hypertension, irrespective of whether they have established CVD.5,6 This decision was taken because the Guideline Development Committee found limited evidence of robust or consistent clinical benefit associated with the use of lower BP targets in people with hypertension and CVD, and no evidence in patients aged over 80 years or in those with an aortic aneurysm.5,6

For patients with hypertension but without established CVD, the Committee did not recommend a lower target systolic BP, such as 120 mmHg, because evidence from the SPRINT Trial (a large study conducted in the US) showed that tight control of BP targets may increase the risk of injury from falls or acute kidney injury, outweighing benefits such as reduced mortality and CVD events.5,7

Early detection and treatment of hypertension is vital to improve healthcare outcomes and reduce the burden on the health service associated with avoidable complications of the condition. This article provides practical advice on implementing the updated recommendations of NG136 to optimise the identification and management of hypertension.

1. Confirm a Diagnosis of Hypertension

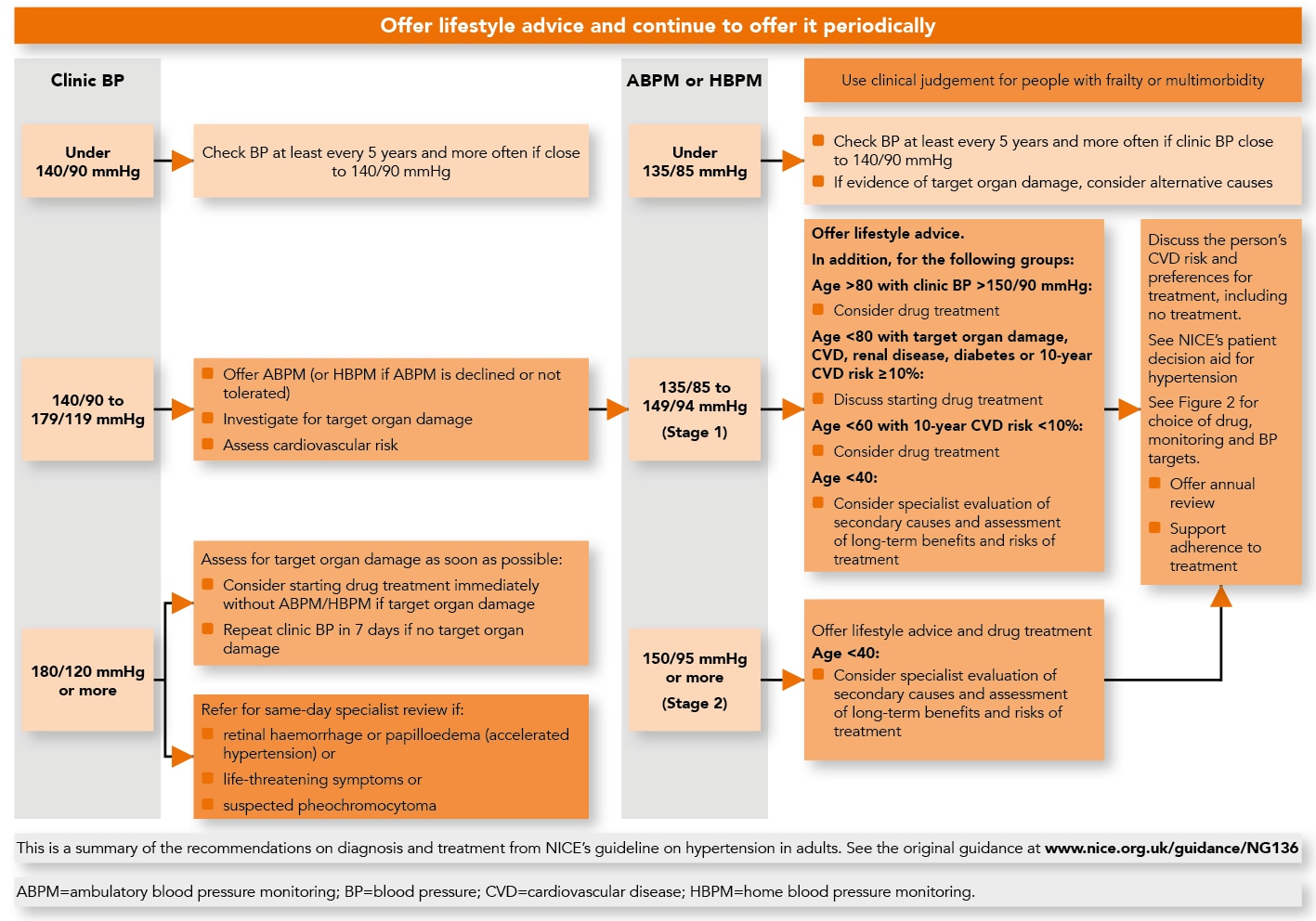

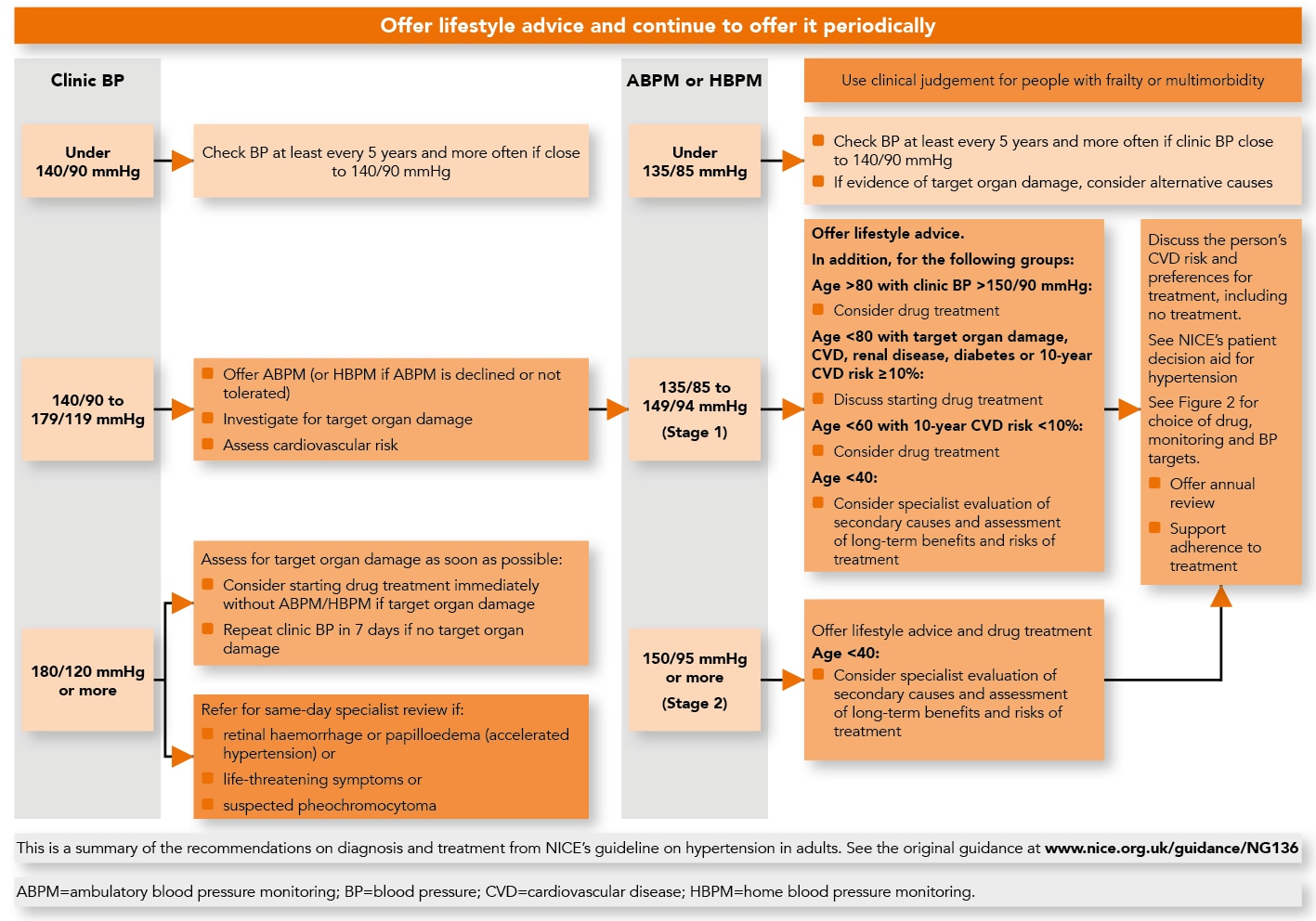

The diagnosis and treatment of hypertension is summarised in Figure 1.8 Treatment options will depend on the stage of hypertension (see Box 1),9 whether the patient has any current comorbidities including established CVD, and whether their current estimated 10-year risk of CVD is 10% or more.8

© NICE 2022. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Visual summary—hypertension in adults: diagnosis and treatment. NICE, 2022. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/visual-summary-pdf-6899919517 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

| Box 1: Stages of Hypertension9 |

|---|

© NICE. Hypertension: how should I diagnose hypertension? NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypertension/diagnosis/diagnosis/ (accessed 17 June 2022). All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. |

If a clinic BP reading is 140/90 mmHg or higher, then the patient is considered at risk of hypertension.5 In this scenario, NICE states that clinicians should:5

- take a second measurement during the consultation

- if the second measurement is substantially different from the first, take a third measurement—record the lower of the last two measurements as the clinic blood pressure

- if clinic blood pressure is between 140/90 mmHg and 180/120 mmHg, offer ABPM to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension

- if ABPM is unsuitable or the person is unable to tolerate it, offer HBPM to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension.

An ABPM daytime average or HBPM average of 135/85 mmHg or higher will confirm a diagnosis of hypertension.5 When using ABPM to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, NICE advises practitioners to ensure that at least two measurements per hour are taken during the person’s usual waking hours (for example, between 08.00 and 22.00).5 The average value of at least 14 measurements taken during the person’s usual waking hours should be used to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension.5

When using HBPM to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, clinicians should ensure that:5

- for each BP recording, two consecutive measurements are taken, at least 1 minute apart and with the person seated and

- BP is recorded twice daily, ideally in the morning and evening and

- BP recording continues for at least 4 days, and ideally for 7 days.

The measurements taken on the first day should be discarded, and the average value of all the remaining measurements used to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension.5

When to Refer

Patients should be referred for same-day specialist review if they have a clinic BP of 180/120 mmHg and higher with:5

- signs of retinal haemorrhage or papilloedema (accelerated hypertension) or

- life-threatening symptoms, such as new-onset confusion, chest pain, signs of heart failure, or acute kidney injury.

In addition, NICE recommends that people with suspected pheochromocytoma (for example, labile or postural hypotension, headache, palpitations, pallor, abdominal pain, or diaphoresis) should be referred for same-day specialist assessment.5

Practitioners should also consider seeking a specialist evaluation (not necessarily a same-day review) for adults aged less than 40 years with hypertension, or for those with resistant hypertension on the maximum tolerated dose of antihypertensive medications.5

2. Assess Target Organ Damage in Patients With Primary Hypertension

Around 90% of patients with hypertension are classified as having primary hypertension—that is, hypertension with no identifiable cause.10 NICE states that all patients with hypertension should be offered the following investigations to check for target organ damage:5,11

- test for the presence of protein in the urine by sending a urine sample for estimation of the albumin:creatinine ratio, and test for haematuria using a reagent strip

- take a blood sample to measure

- glycated haemoglobin (to test for diabetes)

- electrolytes, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (to test for chronic kidney disease)

- total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (to aid in assessing cardiovascular risk)

- examine the fundi (for the presence of hypertensive retinopathy)

- arrange for a 12-lead electrocardiogram to be performed (to assess cardiac function and detect left-ventricular hypertrophy).

Assessing Cardiovascular Risk

Also, clinicians should assess 10-year risk of developing CVD using a tool such as the QRISK® assessment tool (qrisk.org/three/),11 and consider pharmacological treatment (for example, 20 mg atorvastatin) for primary prevention of CVD if the score is 10% or more.12

3. Identify Secondary Causes of Hypertension

Secondary hypertension accounts for 10% of cases of hypertension, and is defined as hypertension with a known underlying cause.10 Common causes of secondary hypertension include:

- vascular disorders11

- thyroid problems11

- renal disorders11

- pregnancy13

- obesity13

- endocrine disorders11

- obstructive sleep apnoea11

- use of certain drugs (for example, sympathomimetics, which may be found in over-the-counter cough and cold remedies)11

- use of other substances (for example, alcohol).11

Healthcare professionals should consider the need for specialist investigations in people with a suspected secondary cause of hypertension.5

4. Understand the Consequences of Untreated Hypertension

Most people with high BP do not exhibit any signs or symptoms, even if their BP is dangerously high, which is why hypertension is described as a ‘silent killer’.14 Hypertension is often detected by measuring BP as part of a routine appointment or via an opportunistic screening.15

Uncontrolled high BP gives rise to an increased risk of the following conditions:2

- heart disease

- heart attack

- stroke

- heart failure

- peripheral arterial disease

- aortic aneurysm

- kidney disease

- vascular dementia.

The impact that undiagnosed and untreated hypertension has on patients’ lives is continuous. Each 2-mmHg rise in systolic BP is associated with a 7% increased risk of mortality from ischaemic heart disease and a 10% increased risk of mortality from stroke.16

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Ettehad et al (2015) found that a 10-mmHg reduction in systolic BP resulted in the following:17

- a 20% reduction in the risk of major CVD events

- a 17% reduction in coronary heart disease

- a 27% reduction in stroke

- a 28% reduction in heart failure

- a significant 13% reduction in all-cause mortality.

5. Consider Patient Characteristics When Choosing Pharmacological Treatments

Figure 2 shows the choice of antihypertensive drugs, methods of monitoring treatment, and BP targets recommended by NG136 depending on an individual patient’s characteristics.8

© NICE 2022. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Visual summary—hypertension in adults: diagnosis and treatment. NICE, 2022. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/visual-summary-pdf-6899919517All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

Regarding the choice of oral antihypertensives, NICE makes the following recommendations:

- if an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) is not tolerated, for example because of cough, offer an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) to treat hypertension5

- do not combine an ACEi with an ARB to treat hypertension5

- this is because of a risk of hyperkalaemia18

- measure urea and electrolytes 1–2 weeks and BP 2–4 weeks after treatment initiation19

- if there is evidence of heart failure or oedema, offer a thiazide-like diuretic such as indapamide instead of a calcium-channel blocker5

- however, exercise caution if the patient has gout or diabetes20

- for adults with hypertension already receiving treatment with bendroflumethiazide or hydrochlorothiazide who have stable, well-controlled BP, continue with their current treatment5

- if a patient with hypertension becomes pregnant, they should be offered referral to a specialist.21

For adults of Black African or African–Caribbean family origin, consider an ARB in preference to an ACEi;5 this is because of an increased risk of angioedema in these populations.22

Treatment Choice in Patients With Hypertension and CVD

The evidence reviewed by NICE showed that there was no clinically important difference in the effectiveness of antihypertensive drugs in hypertensive patients with or without established CVD.23 There was limited evidence for the use of some treatment options in people with stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), and coronary artery disease.23 However, NICE stated that evidence did not cover enough treatment comparisons for the Committee to draw any firm conclusions; therefore, no changes to the treatment algorithm was justifiable in these groups.23

To avoid confusion over the treatment pathway, NICE advises clinicians that disease-specific recommendations on acute coronary syndromes and chronic heart failure should be applied first (for example, when prescribing an ACEi or an ARB for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction).5 Recommendations on drug treatment that overlap with treatment for hypertension are shown in Box 2.5,24–28

In terms of how these recommendations may affect practice, the Committee was aware that, after a stroke, the thiazide-like diuretic indapamide is sometimes used first, rather than a calcium channel blocker.5 However, NICE states that it is unclear how common this is.5 As people with established CVD are commonly prescribed more than one oral antihypertensive drug, any impact on prescribing would be limited.5,23

6. Reduce and Maintain BP Below the Appropriate Target

Regarding BP targets, the main emphasis of the 2022 guideline update is that clinicians should reduce and maintain BP below the appropriate target.5 For example, for adults under 80 years of age, clinic BP should be reduced to below 140/90 mmHg and maintained below that level.5 This is because the majority of the control arms of the studies that the NICE Committee examined achieved BP well below 140/90 mmHg.5,6

In terms of the potential impact of the updated guideline on patients with hypertension, particularly those with cardiovascular disease, there should be no change in practice or increase in NHS resource use.6 National quality indicators used in primary care, such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in England,29 do not use a lower BP target for separate CVD registers such as those for stroke and TIA. Therefore, using the same BP targets is keeping in line with most existing clinical practice.6

7. Get Involved in Campaigns to Raise Awareness of Hypertension

In May 2022, campaigns such as World Hypertension Day30 and May Measurement Month31 helped to raise awareness of high BP around the world.32 These campaigns were particularly important this year because during the pandemic there was a significant reduction in diagnosing, monitoring, and treating hypertension, as well as in identifying other risk factors for CVD. On 5–11 September 2022, practices have the opportunity to get involved in another hypertension campaign—Know Your Numbers! Week.33 Local premises, such as gyms, leisure centres, and libraries, and employers can register to take part by hosting ‘pressure stations’ and encouraging the public to have their BP checked. The risks of high BP are explained, and people may potentially be diagnosed with hypertension and advised of the next steps.33

8. Capitalise on Case-finding by Community Pharmacy

Although the NHS has increased its uptake of technologies enabling remote monitoring of BP—such as the BP @ Home Service, which provided over 220,000 home BP monitors to patients in England34 —2 million fewer people in England were recorded as having controlled hypertension in 2021 than in 2020.32

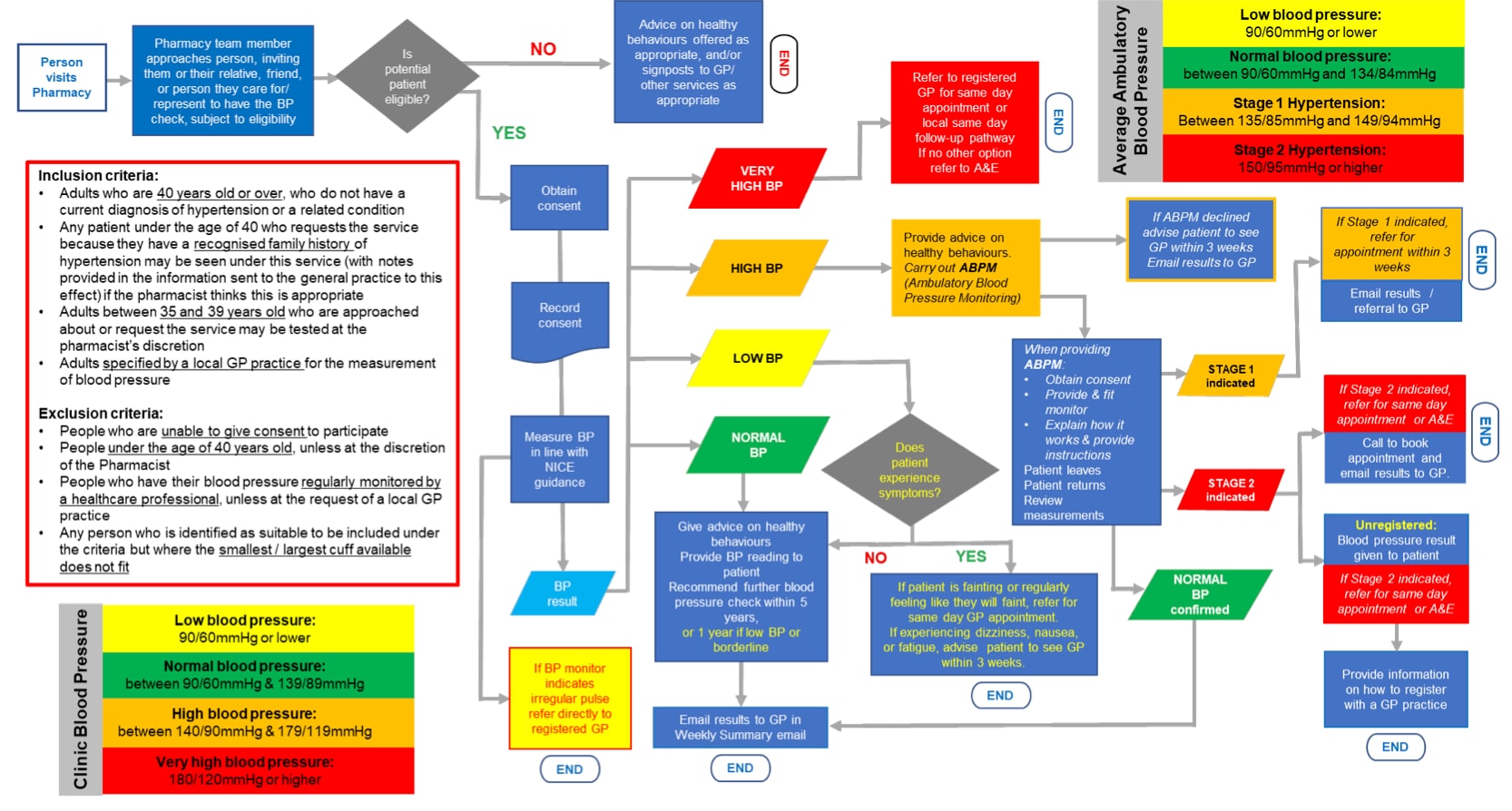

New approaches are needed to improve detection of the condition, such as utilising community pharmacies to screen for high BP. The new Hypertension Case-Finding Advanced Service Specification outlines the key role of community pharmacy in detecting hypertension in primary care networks (PCNs).35 As of May 2022, more than 6800 community pharmacies in England have signed up for the NHS Community Pharmacy Hypertension Case-Finding Service, and over 75,000 BP checks have been carried out so far.32

The Hypertension Case-Finding Advanced Service Specification protocol is shown in Figure 3.35 Pharmacies offer an opportunistic BP check in line with NG136 to eligible people.35,36 If hypertension is detected, pharmacies will also carry out ABPM and share the results with the patient’s practice should they require monitoring and treatment.35,36 Practices can then initiate treatment for hypertension where necessary to help improve healthcare outcomes.

ABPM=ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; A&E=accident and emergency; BP=blood pressure; CCB=calcium-channel blocker

NHS England and NHS Improvement. Advanced service specification. NHS community pharmacy hypertension case-finding advanced service (NHS Community Pharmacy Blood Pressure Check Service). Version 1, 11 November 2021. London: NHSE&I, 2021. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/B0953-NHS-community-pharmacy-blood-pressure-check-service-specification.pdf

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

In this way, pharmacists can work as part of the multidisciplinary primary care team to improve the identification and management of patients with hypertension. This has the potential to enhance health outcomes for patients, provide value for money to practices (through meeting QOF indicators and ensuring cost-effective prescribing) and pharmacies, and reduce the workload in general practice. Pharmacists already have the necessary skills to manage patients with hypertension in patient-facing clinics, as clinical management is primarily based on managing medication and reducing inappropriate polypharmacy, as well as providing dietary and lifestyle advice to patients.37

9. Harness the Wider Benefits of Lifestyle Interventions

Recommendations on lifestyle interventions are retained in the updated NG136.5 As well as offering regular lifestyle advice to people with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, NICE recommends the following nonpharmacological interventions:

- asking about people’s diet and exercise patterns, and offering appropriate written or audiovisual materials to promote healthy lifestyle changes5

- regular physical exercise can reduce BP5 —for example, at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity a week38

- a healthy diet can also lower high BP5

- encourage reduced intake of alcohol if patients drink excessively5 —for example, no more than 14 units per week for men and women38

- discourage excessive caffeine consumption5,38

- encourage people to keep their dietary sodium intake low, either by reducing (for example, to less than 6 g per day14) or substituting sodium salt; however, clinicians should be aware that some salt substitutes containing potassium chloride should not be used by older people, people with diabetes, pregnant women, people with chronic kidney disease, and people taking some antihypertensive drugs, such as ACEis and ARBs)5

- offering advice and helping smokers to stop smoking2,5

- signposting to local initiatives or patient organisations to provide support and promote healthy lifestyle changes5 —for example, walking clubs.39

Diet

The Association of UK Dietitians recommends a balanced diet containing fruits, vegetables, and wholegrains that are rich in potassium, magnesium, and fibre, as well as calcium from low-fat dairy products, rather than dietary supplements.38 Consuming at least one portion a week of oily fish (such as salmon, sardines, or mackerel) that is high in omega-3 fatty acids is also recommended to reduce high BP.38

Another evidence-based diet that is currently gaining momentum in the US is the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet,40 a similar version of which has been shown to reduce average BP by around 8–14 mmHg.41 The DASH diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, wholegrains and low-fat dairy, with reduced saturated fat, total fat, and sodium intake.42

Stress

In addition to dietary changes, managing stress levels is also important because stress can cause BP to rise.38 Patients should be encouraged to get enough sleep, adopt relaxation techniques, and even ask for help when overburdened to reduce their stress levels, which in turn may help to lower their BP.38 However, a recommendation on relaxation therapies was removed from NG136 back in 2011 as there was insufficient evidence of a beneficial effect on BP.5

Environmental Benefits

As well as covering the health benefits to patients, shared decision-making conversations between clinicians and patients in primary care consultations should also include a discussion of the planetary health benefits of lifestyle interventions. For example, walking or cycling instead of driving may improve a patient’s health and wellbeing and reduce elevated BP, but also has the potential to reduce local air pollution and lower carbon emissions.43,44

Similarly, the EAT-Lancet Commission Report states that a diet that is good for human health is also good for planetary health.45

Furthermore, if nonpharmacological interventions can help to reduce or limit the progression of BP, this may help to reduce polypharmacy and the carbon footprint associated with medicines, packaging, and visits to GPs and pharmacies. Patients are already advised to only order the medications they need to avoid wastage, and not to dispose of unwanted medicines in normal waste collections or flush them down the toilet (which may cause water pollution).46 Patients should return any unwanted medicines to community pharmacies for their safe disposal.

10. Signpost Patients, Their Families and Carers, and Healthcare Professionals to Useful Resources

NICE has produced a patient decision aid that healthcare professionals can discuss with their patients.47 The decision aid explains the available treatment options if they have established CVD or if their current estimated 10-year risk of CVD is 10% or more.47

Useful online resources that primary care clinicians can signpost their patients to are listed in Box 3. Families and carers can help support their loved ones by getting involved in understanding how hypertension is diagnosed, and what can be done to reduce BP.

| Box 3: Useful Resources |

|---|

For Patients

For Healthcare Professionals

|

Summary

The updates to NG136 focus on individuals with hypertension and established CVD.5 Given that people with established CVD have a fundamentally higher risk of CVD events than patients without CVD, NICE recommends that the benefits of further reduction in BP targets may outweigh any potential risks. Early detection of hypertension is vital to reduce risk of CVD and other related complications. Primary care clinicians can make a significant impact on this group of patients by utilising case-finding by community pharmacies, working within PCNs to help prevent further CVD events.

| Key Points |

|---|

NG=NICE Guideline; BP=blood pressure; CVD=cardiovascular disease |

Muhammad Siddiqur Rahman

Clinical Practice-Based Pharmacist Prescriber and Trainee Advanced Clinical Practitioner, Court View Surgery, Kent; Co-Director of the Pharmacist Cooperative; member of Pharmacy Declares

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you to consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system; QOF=Quality and Outcomes Framework; ABPM=ambulatory blood pressure monitor; HBPM=home blood pressure monitor; CVD=cardiovascular disease |

| Implementation Actions for Clinical Pharmacists in General Practice |

|---|

Written by Sukhpreet Rai, Clinical Services Pharmacist, Soar Beyond Ltd With an estimated 46% of adults with hypertension across the world unaware that they have the condition,[A] GP clinical pharmacists have an interesting role to play in managing these patients in both an opportunistic and targeted way. The following implementation actions are designed to support clinical pharmacists in general practice to optimise hypertension management in line with NG136:

The i2i Network has a suite of training and implementation resources, both free and bespoke, for GP Clinical Pharmacists, including e-learning and on-demand training delivered by experts covering a range of long-term conditions. Become a free member at: www.i2ipharmacists.co.uk/ or find out more at www.soarbeyond.co.uk [A] World Health Organization. Hypertension. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed 12 July 2022). [B] NICE. How do I control my blood pressure? Lifestyle options and choice of medicines. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/how-do-i-control-my-blood-pressure-lifestyle-options-and-choice-of-medicines-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6899918221 (accessed 12 July 2022). [C] NHS England. Online version of the NHS long term plan. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed 12 July 2022). [D] NHS England. Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for 2021/22. London: NHS England, 2021. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/B0456-update-on-quality-outcomes-framework-changes-for-21-22-.pdf NG136=NICE Guideline 136; MDT=multidisciplinary team; BP=blood pressure; CVD=cardiovascular disease; UKHSA=UK Health Security Agency; QOF=Quality and Outcomes Framework |