Dr Anne Connolly Explores the Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Complexities, and Comprehensive Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) in Primary Care

| Read This Article to Learn More About: |

|---|

Find key points and implementation actions for STPs and ICSs at the end of this article |

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex, long-term condition with metabolic, reproductive, and psychological sequelae requiring a holistic approach to management. This condition is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age, with an estimated prevalence of 10–20%,1 but there are no clear guidelines for management.

First described by Stein and Leventhal in 1935 in a published case series of seven patients with amenorrhoea and bilateral polycystic ovaries, PCOS was originally labelled the Stein-Leventhal syndrome.2 In 2004, after many years of debate, the Rotterdam criteria for diagnosis were agreed;3 these criteria require two of the following three features, provided alternative causes of hyperandrogenism have been excluded:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

Pathophysiology

Traditionally, PCOS has been managed as a gynaecological condition; however, the underlying pathophysiology of PCOS usually stems from an endocrine abnormality resulting from insulin resistance.4 In the majority of cases seen in the UK the insulin resistance is aggravated by weight gain, which in turn exacerbates the clinical, reproductive, and metabolic features of the condition.

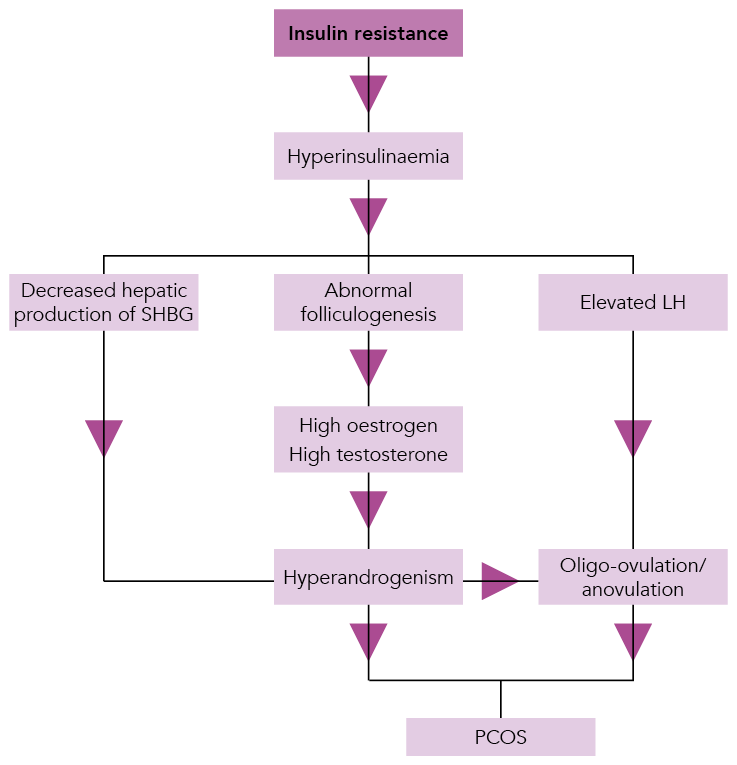

Insulin resistance leads to hyperinsulinaemia and subsequent abnormal follicular development, which in turn brings about elevated oestrogen and androgen levels. The systemic effects are exacerbated by a reduction in sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) along with persistently elevated luteinising hormone (LH) levels, which prevents ovulation. High levels of circulating free androgens are responsible for the clinical features associated with PCOS, and the absence of ovulation causes unopposed oestrogen stimulation on the endometrium (and associated hyperplasia).4 The hormonal changes that influence the development of PCOS are illustrated in Figure 1.

SHBG=sex hormone binding globulin; LH=luteinising hormone; PCOS=polycystic ovary syndromeSource: Reproduced with permission. Connolly A, Beckett V. Polycystic ovary syndrome—management of a long-term condition in primary care. In: Connolly A, Britton A, editors. Women’s health in primary care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017: 111–118. © Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Clinical Features

There are a number of clinical features of PCOS to look out for (see Table 1). The initial concerns of women with PCOS are usually the consequences of hyperandrogenism, including:4

- hirsutism (male pattern hair distribution):

- secondary to excessive circulating androgens

- occurs in 60–80% of women with PCOS

- new onset acne in adult women

- acanthosis nigricans (darkened plaques on the neck, armpits, groin, and elbows):

- found in women with insulin resistance and is a common presentation in women with PCOS.

Table 1: Clinical Features of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome4

| Short-term Features | Long-term Metabolic Features | Other Associated Concerns |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Reproduced with permission. Adapted from Connolly A, Beckett V. Polycystic ovary syndrome—management of a long-term condition in primary care. In: Connolly A, Britton A, editors. Women’s health in primary care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017: 111–118. © Cambridge University Press, 2017. | ||

Overt virilisation is not a feature of PCOS and requires investigation to exclude an androgen-secreting tumour or late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

The irregular, infrequent, or absent menses and reduction in fertility are a result of the oligo-ovulation and anovulation caused by PCOS. Chronic anovulation, which occurs alongside obesity in many women with PCOS, causes excessive unopposed oestrogenic stimulation to the endometrium and may result in dysfunctional bleeding as the endometrial shedding is erratic, which may eventually lead to endometrial hyperplasia or cancer.

Long-term effects of PCOS are usually dependent on levels of obesity, similar to the consequences of insulin resistance that are routinely managed in women with diabetes.

Psychological Features

Women with PCOS are more likely to experience anxiety or depression than the general population.4 The lack of self-esteem due to concerns about body image and appearance aggravated by any concerns about fertility can lead to depression, eating disorders, psychosexual issues, and relationship problems.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PCOS is usually made from history and clinical examination using the Rotterdam criteria.3 However, it is important to consider other causes of hyperandrogenism; e.g. congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumours, Cushing’s syndrome, and other causes of oligo-ovulation and amenorrhoea (such as hypothyroidism, hyperprolactinaemia, or premature menopause).

Appropriate investigations might include:

- serology for follicle stimulating hormone, LH, prolactin, and thyroid function

- testosterone testing; the role of testosterone testing is complex as total testosterone levels do not vary much due to the low levels usually found in women:

- serum total testosterone levels may be useful to differentiate between the mildly elevated levels seen in PCOS (<5.0 nmol/l) compared with the higher levels (>5.0 nmol/l) found with other causes of hyperandrogenism

- depending on local laboratory arrangements, measuring SHBG alongside a total testosterone level allows calculation of the more reliable and useful free androgen index

- a transvaginal and pelvic ultrasound scan can enable the examination of ovarian and endometrial pathology in detail:

- ultrasound findings diagnostic of PCOS are the presence of increased ovarian volume (>10cm3) and/or more than 12 peripheral follicles in each ovary, measuring 2–9mm in diameter,5 described as the ‘ring of pearls’ effect

- because of the increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in obese women with PCOS with oligo-ovulation or anovulation, ultrasound findings of a thickened or cystic endometrium require referral for hysteroscopy.6

Additional investigations are indicated following a cardiovascular risk assessment, as with any patient presenting with insulin resistance:

- glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is indicated at diagnosis and on an annual basis in women with PCOS and elevated body mass index (BMI) as routine practice for women at risk of developing diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- lipid levels

- renal function

- liver function.

Management

A holistic approach to care is required for women with PCOS. Management should aim to support patients with the short-term features and long-term risks associated with the complex nature of this condition.

In the author’s clinical experience, PCOS is more common in women who are overweight (it is important to note that not all women with PCOS are overweight). Weight management advice should be offered and should include recommendations about diet and exercise, with the aim of reducing insulin resistance. Weight reduction also reduces androgen levels and the systemic effects of ovarian dysfunction, leading to improvement in dermatological symptoms, increased ovarian function, and reduced long-term effects of insulin resistance. Alternative treatments should be chosen based on clinical presentation.

Short-term Consequences

Hyperandrogenism

Hyperandrogenism symptoms are managed by any treatment that reduces circulating free androgens. Weight reduction achieves this by increasing levels of SHBG, as will any medication containing ethinyl-oestradiol, i.e. using any combined hormonal contraceptive (following a risk assessment for use).

Cyproterone acetate may be used alone or in combination with 35 mcg ethinyl-oestradiol. The combination of ethinyl-oestradiol and drospirenone (which has anti-androgenic activity) may also be helpful in some women with concomitant acne. However, it may take up to 9 months for these hormonal treatments to have a significant effect. Specialist dermatology referral may be necessary for treatment of hirsutism or to consider prescription of isotretinoin for acne.

Psychological Concerns

Screening for psychological and psychosexual concerns is an important aspect of the holistic care that women with PCOS require; they should be offered ongoing support, and medication with antidepressants should be available as usual for any patient seen in primary care.

Fertility

Reduced fertility is common in women with oligo-ovulation or anovulation. Weight reduction in women with PCOS and BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 can improve fertility, and optimising weight prior to conception leads to better outcomes, both for mother and foetus.7 Problems more commonly experienced during pregnancy for women with PCOS include gestational diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-related hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and premature delivery.8

The Endocrinology Society guideline on cardiovascular disease in patients with PCOS indicates that women intending to manage the risk of complications in future pregnancies (e.g. by reducing BMI, controlling hypertension) with assistance from statins or antihypertensives should be on reliable contraception until treatment is stopped or changed to medicines that are not contraindicated in pregnancy.9

The role of metformin in improving fertility outcomes in women with PCOS has been contentious and confusing as there has been the assumption that metformin assists with weight reduction and improving fertility. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) scientific impact paper on Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with PCOS has disputed this supposition with the results of recent studies demonstrating no difference between women with PCOS using metformin and those using placebo. Metformin is recommended as first-line treatment in the management of type 2 diabetes. Metformin can be used in women with PCOS when diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is confirmed, but not purely for improving fertility, as there are better first- and second-line treatments for improving fertility in PCOS than metformin alone.10

It should be noted that although metformin is commonly used in UK practice in the management of diabetes in pregnancy and lactation, and there is strong evidence for its effectiveness and safety, metformin does not have a marketing authorisation for this indication. Prescribers should follow relevant professional guidance, taking full responsibility for the decision. Informed consent should be obtained and documented. See the General Medical Council’s Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices for further information.11

Long-term Consequences

The RCOG guideline on Long-term consequences of polycystic ovary syndrome highlights the need for monitoring of women with PCOS in view of their increased risk of cardiovascular disease resulting from obesity, hyperandrogenism, hyperlipidaemia, and hyperinsulinaemia.12

The key conditions that the RCOG guideline recommends screening for are:12

- cardiovascular disease:

- in the US, up to 70% of women with PCOS may have dyslipidaemia and over one-third have metabolic syndrome9

- diabetes:

- as PCOS is associated with insulin resistance, oral glucose tolerance (OGT) testing at diagnosis12,13 and then on a regular basis depending on risk factors (e.g. BMI, ethnicity, family history of type 2 diabetes, history of gestational diabetes mellitus) is required; HbA1c testing is also reasonable if women are unwilling to have an OGT or where the resources for an OGT are not readily available.12

Long-term management should include reducing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer caused by the high circulating levels of unopposed oestrogen in women with chronic oligo-ovulation and anovulation, particularly if the patient is also overweight.

The 2018 update of NICE Guideline 88 on Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management recommends considering endometrial biopsy at the time of hysteroscopy for women who are at high risk of endometrial pathology, including women with infrequent heavy bleeding who are obese or have PCOS.14`

If the endometrium is normal in thickness and needs protection from endometrial hyperplasia, treatment options include:15

- a levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system (LNG-IUS)

- combined hormonal contraception following risk assessment

or

- an induced withdrawal bleed, using intermittent progestogen therapy with medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily for 14 days, every 3–4 months in women with PCOS who have prolonged episodes of amenorrhoea.

An example case study covering the diagnosis and management of a patient presenting with PCOS can be found in Box 1.

| Box 1: Case Study of a Patient Experiencing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

|---|

Amy is a 29-year-old primary school teacher who attends morning surgery and bursts into tears as the consultation begins. She is concerned about her fertility as she and her partner, Karl, have been trying to conceive for the past 3 years. They have one child, Chloe, aged 5, who was conceived very quickly. When asked further she complains that since Chloe was born she has been missing periods, which now occur every 3–5 months. She performs many pregnancy tests thinking that each delayed period is due to a pregnancy, adding to her distress. She also thinks that Karl is starting to find her unattractive as she now weighs 105 kg, and is spending her spare money on make-up to hide the acne she has developed on her face and laser treatment to remove the increasing problem she has noticed with facial hair. The diagnosis of PCOS can be made from her infrequent periods and symptoms of hyperandrogenism. The investigations required for of this patient are minimal; she is offered HbA1c and liver function tests. Other fertility tests should be considered for Amy and Karl as per local protocol. Amy is signposted to Verity website, the UK resource for women whose lives are affected by PCOS, for information and management recommendations about her condition. She is offered a follow-up appointment for the ongoing support she requires. Ideally, she should be offered contraception until she loses sufficient weight to improve her ovarian function and her pregnancy outcomes. PCOS=polycystic ovary syndrome; HbA1c =glycated haemoglobin |

Conclusion

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a complex life-long endocrine condition with short-term features and long-term consequences. There are no clear guidelines for the diagnosis and management of this common condition; however, the majority of care can be provided in the primary care setting. Further sources of information about caring for patients with PCOS are listed in Box 2.

Women with PCOS require holistic care including psychological support and information to empower them to understand the importance of weight reduction in reducing the symptoms and long-term consequences of the condition. See Box 3 for details of support materials and resources that can be shared with patients.

| Box 2: Supplementary Reading for Care of Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

|---|

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary—Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Box 3: Support Materials and Organisations for Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

|---|

Verity. Verity—sharing the truth about PCOS |

Dr Anne Connolly

GP, Bevan Healthcare, Bradford; GPwSI in Gynaecology

Clinical Commissioning Group Board member with remit for maternity, children and young people, Bradford City, Bradford Districts, and AWC CCGs

Chair of the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum

RCGP Clinical Champion for menstrual wellbeing

| Key Points |

|---|

|

| Implementation Actions for STPs and ICSs |

|---|

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon

PCOS=polycystic ovary syndrome |